"To the uninitiated, the emblem is indeed an esoteric artifact from the Early Modern Period. Its combinatory possibilites, however, associate it in many ways with the idea of the Renaissance individual - a person of many gifts and surprising talents whose charm consists of fresh new perspectives and engaging ideas. The emblem is very much the product of its age, combining texts and images in innovative ways for educational, devotional, entertainment, political and amorous purposes."

"The ideal emblem is typically described as a tripartite structure, comprised of motto (inscriptio), image (pictura), and epigram (subscriptio), and appeared in all European vernacular languages and latin. While emblems decorated secular and sacred architecture, objets d'art, and even everyday furniture and ephemeral art, such as triumphal arches for a monarch's entry, often emblems were published in books, and collections of emblems appearing in such volumes frequently, but not always, centred on a special theme or topos."

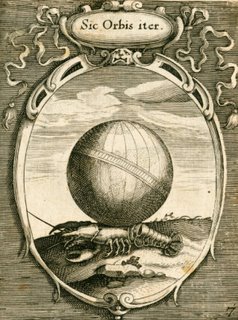

"The sense of this arcane image and its texts is something like that proverbial saying 'two steps forward, one step backward'. The reader must know something about natural history and that crayfish scuttle backwards. Thus, the crayfish, with the globe on its back symbolizes the way of the world, or sic orbis iter. The epigram [not shown] deepens the message and relates it to a moral lesson, admonishing the reader to avoid the slippery slope of worldly things and to follow the divine path."

"The sense of this arcane image and its texts is something like that proverbial saying 'two steps forward, one step backward'. The reader must know something about natural history and that crayfish scuttle backwards. Thus, the crayfish, with the globe on its back symbolizes the way of the world, or sic orbis iter. The epigram [not shown] deepens the message and relates it to a moral lesson, admonishing the reader to avoid the slippery slope of worldly things and to follow the divine path."

German printer, draftsman and engraver, Peter Is(s)elburg (1658-1630) was a significant artist from the Cologne and Nuremburg areas. He had a wide area of subject matter from lampoons and portraits to cityscapes, religious images and costumery. His legacy also included a large portfolio of emblemata.

- The images here come from Emblemata Politica In Aula Magna Curiae Noribergensis Depicta: quae sacra virtutum suggerunt monita, prudenter administrandi, fortiterque defendendi Rempublicam published in 1617, hosted at this University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign site. [this link works as at December 2012]

- There are 32 engravings in total and after I finished uploading these examples I found that Isselburg's work is also online at Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel and the best way to see all the emblems together in thumbnail format is via this Menemosyne intermediary website (clicking through each image takes you to the original jpeg file at HAB-W : and these are arguably a better/clearer product and they are also a bit larger).

- For anyone keen, the above quotes were snagged from "Digital Collections and the Management of Knowledge: Renaissance Emblem Literature as a Case Study for the Digitization of Rare Texts and Images" comprising a dozen seminar topics that were attended by all the major emblemata hosting sites in the world in 2003.

- Previous emblem entries here at BibliOdyssey.

- See also: i; ii; iii; iv; v; vi; vii; viii; ix; x at Giornale Nuovo.

4 comments :

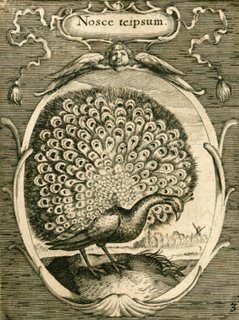

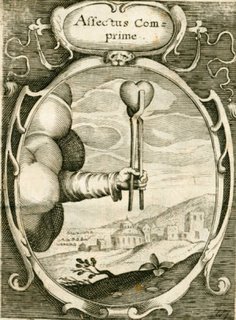

One of the less endearing features of the whole emblem-book phenomenon is how derivative many of the works are, and how much is slavishly copied between the various books. I guess the writers and artists must have struggled to enlarge on the standard moral & pictorial formulae established by Alciato & his contemporaries, or else most of them were unwilling to depart from the established norms. Anyway, once you’ve seen a half dozen disembodied hands coming out of clouds brandishing symbolic objects (athough I must say I don’t specifically recall seeing a heart depicted pinched in a pair of tongs before) the novelty begins to fade. Even so, Isselburg was obviously a skilled artist, and I like his take on Festina Lente but hope no tortoises were impaled during the making of the engraving... and I particularly like the splendid peacock under Nosce te ipsum...

I suppose I'm still enjoying the novelty when the artistry is good quality.

Couldn't such a criticism be easily aimed at many of the emblematic features (as opposed to emblemata, if that makes sense) that adorn books from the 15th to 18th centuries?

The first that comes to mind is Gesner's Historia animalium from the 1550s, the twisted creatures from which were copied from one end of Europe to the other or embellished in one way or another.

Dürer's rhino (and myriad other creations) is another. Obviously there are many more.

These are not genres per se as with the emblemata but one thing that has stuck out for me while traversing all these rare books the last few months has been the amount of blatant filching that went on.

I'm always wondering now about the artist's source material or if something I'm looking at is 'original'. It's human nature I guess, the easier road and all.

You’re quite right that this kind of appropriation isn’t restricted to emblemata and was probably standard, uncontroversial practice in a pre-copyright age. A quote on the subject I found when writing this might bear repeating: book production was dominated by reprints, revised editions and compilations from earlier manuscripts given a new interpretation—by no means always authorized. This type of intellectual exchange, practised across national and linguistic boundaries, finds one of its finest expressions in the emblem literature of the 16th and 17th centuries. Its products also demonstrate a concept of wit and intellect quite different to the modern belief that originality lies in what has never been seen or known before. Holding sway in those days, by contrast, was the ideal of the “ingenious invention,” the extraction of something new from what was familiar and established, and which consequently already held authority.

"..one of its finest expression.." is an interesting way of putting it.

We like to think we (modern society) have moved beyond flagrant ripping off of intellectual property. It's not true from the operating practices of corporations to the muzak from the radio. We may have a more 'official' position against it but it's rife now with improvements in info. exchange.

I wonder how the original artist thought back then though about others taking his work and tweaking it for their own ends and signing their name without attribution?

When you mentioned the hand coming from the clouds I for some reason remembered the Python intro with the cartoon foot (itself a collage from another source if memory serves) squashing out the illustrated opening segment.

Maybe I'm missing/sidestepping the point. With emblemata I'm such an underexposed novice that I still find it very cool examining the imagery, even via secondary sources, although I don't doubt it will wear thin as a strict novelty feeling eventually.

Post a Comment

Comments are all moderated so don't waste your time spamming: they will never show up.

If you include ANY links that aren't pertinent to the blog post or discussion they will be deleted and a rash will break out in your underwear.

Also: please play the ball and not the person.

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.