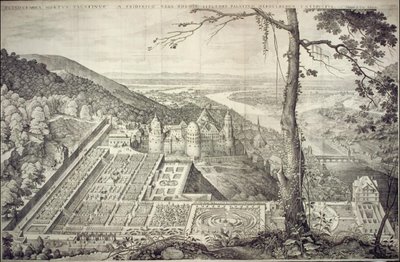

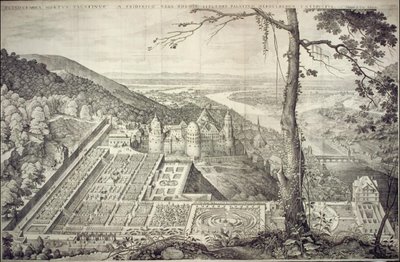

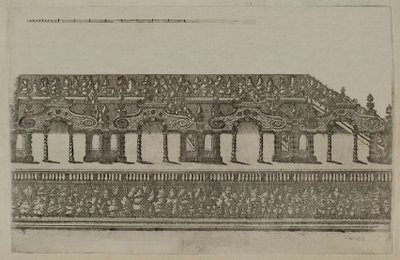

This famous 1620 engraving of

'Hortus Palatinus', (referred to as

the eighth wonder of the world at one stage) is by Matthäus Merian.

- A painting based on Merian's engraving, by Jacques Foucières.

- This photo is a recent vague approximation of the same view.

- Merian is also said to have made another engraving of Heidelberg Castle in 1645 which *I think* is from the opposite direction.1

- 1815 painting by Carl Philipp Fohr.

"Out of a billowy upheaval of vivid green foliage, a rifle-shot removed, rises the huge ruin of Heidelberg Castle, with empty window arches, ivy-mailed battlements, moldering towers—the Lear of inanimate nature—deserted, discrowned, beaten by the storms, but royal still, and beautiful. It is a fine sight to see the evening sunlight suddenly strike the leafy declivity at the Castle's base and dash up it and drench it as with a luminous spray, while the adjacent groves are in deep shadow.

Behind the Castle swells a great dome-shaped hill, forest-clad, and beyond that a nobler and loftier one. The Castle looks down upon the compact brown-roofed town; and from the town two picturesque old bridges span the river. Now the view broadens; through the gateway of the sentinel headlands you gaze out over the wide Rhine plain, which stretches away, softly and richly tinted, grows gradually and dreamily indistinct, and finally melts imperceptibly into the remote horizon.

I have never enjoyed a view which had such a serene and satisfying charm about it as this one gives." [Mark Twain - 'A Tramp Abroad' - 1880]

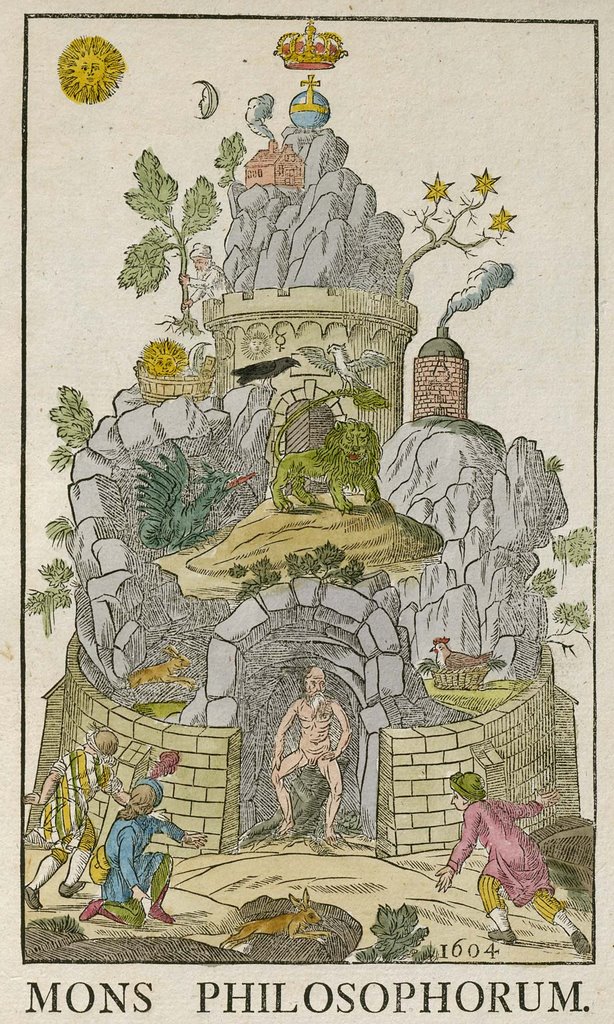

Heidelberg Schloss (castle) is perched on a steep slope 80 metres above the Necker river in south west Germany. Sometime around the end of the 14th century, Prince Elector Ruprecht III built a Royal residence on the site and construction continuted intermittently for the next 400 years. Consequently the palace, which evolved into a fort and then into a castle, contains medieval, baroque, renaissance and gothic architectural elements among its remaining structures.

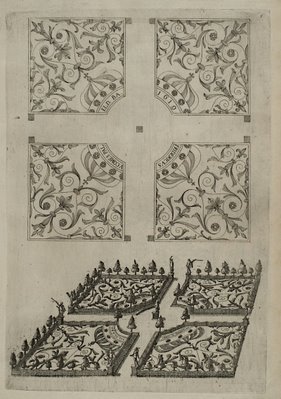

The most significant building work was carried out in the 16th and 17th centuries, beginning (allegedly) with the transfer of columns to the site from a palace that had belonged to Charlemagne. But it was during the time of Prince Elector (and briefly, King) Frederick V that construction of the famed

Schlossgarten (castle garden) was undertaken.

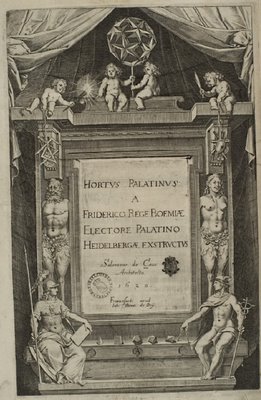

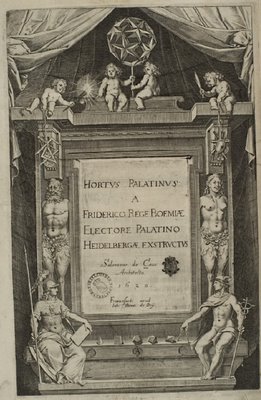

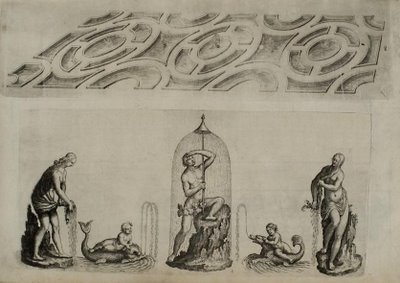

Salomon de Caus

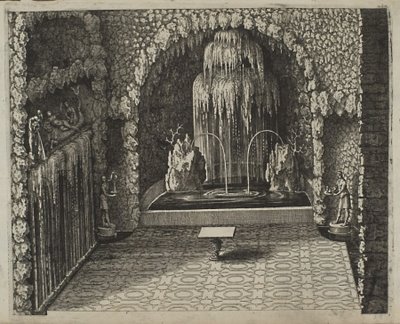

(1576-1626) was a french Huguenot exile who trained primarily as an architect and mathematician. His vocational output extended to geometry, astronomy/astrology and music but he developed into an hydraulic engineer after spending time in Florence with Bernardo Buontalenti at

Pratolino at the end of the 16th century.

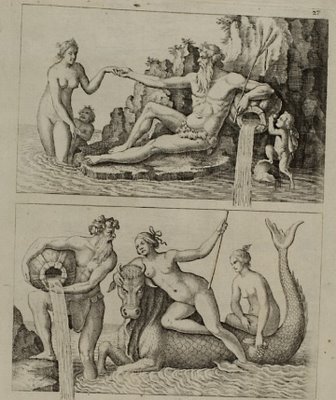

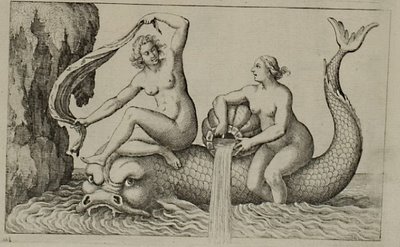

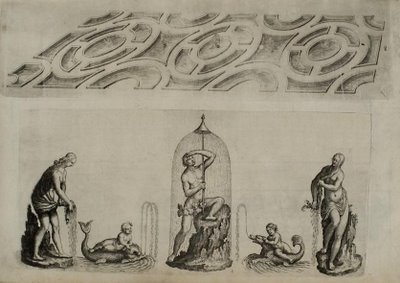

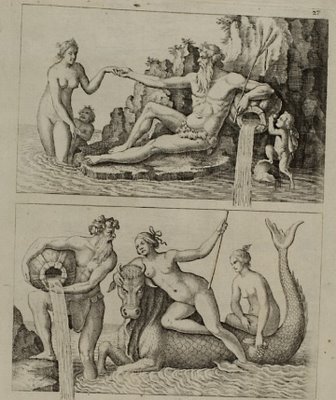

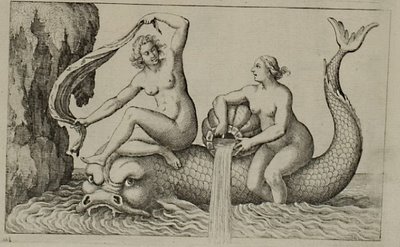

De Caus began designing wells, fountains and hydraulic automata in Belgium and then went to England in the service of the Prince of Wales. He completed several garden designs (some included in his 1612 book, '

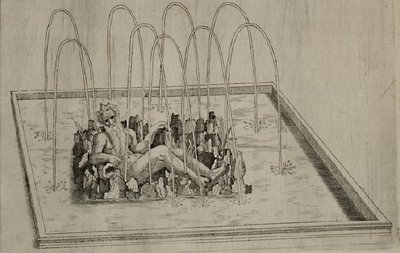

La Perspective, Avec la Raison des Ombres et Miroirs') between educating the royal household in drawing techniques. His interest in waterworks expanded with trick fountains and elaborate ornamental water feature commissions, in which de Caus played a pivotal role in spreading the thematic elements of italian renaissance garden design to northern Europe.

After the death of the Prince of Wales de Caus moved to Heidelberg and employment under Prince Elector Frederick V. Soon afterwards, in 1615, he published his great hyrdraulic work, '

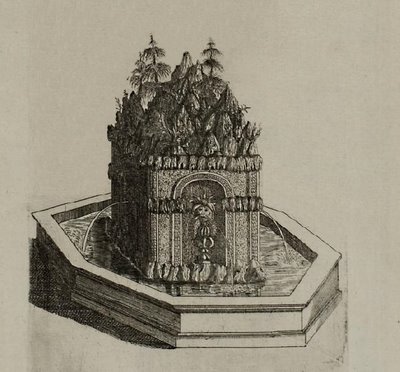

Les Raisons des Forces Mouvantes avec Diverses Machines', which gave rise to the proposition that de Caus had been the first to document a steam engine.

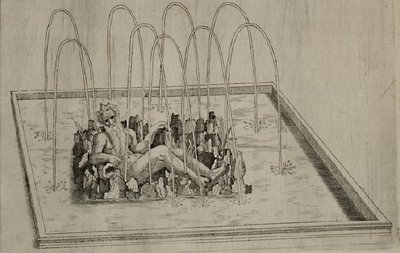

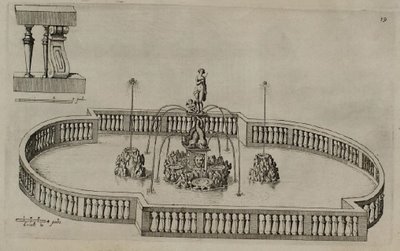

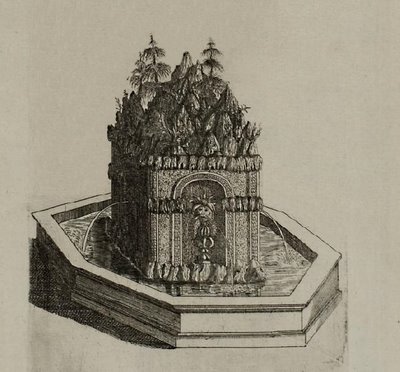

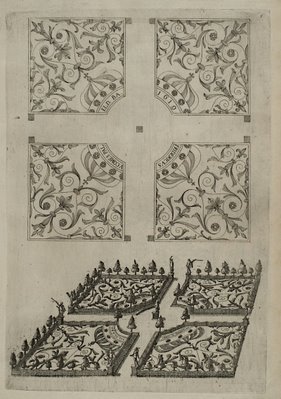

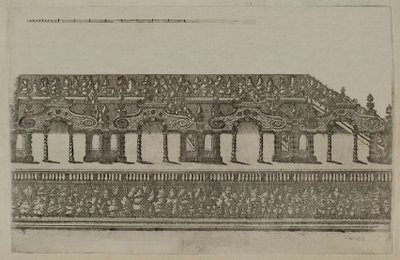

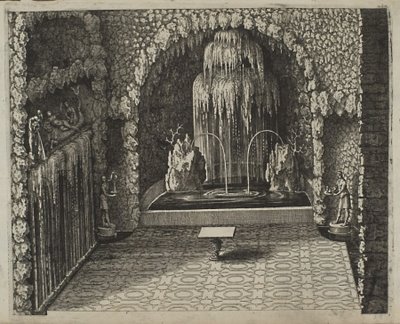

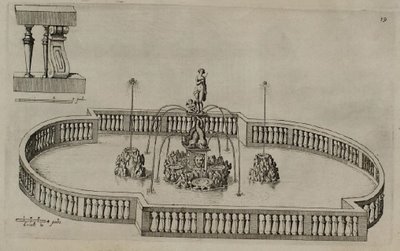

(It's quite amusing seeing the different wording on this topic between the french (trans.) and english wikipedia accounts - doubtless it was a link in the chain of knowledge however)De Caus spent 5 years designing and constructing the renowned

hortus palatinus (palace garden) for the Prince Elector, which included grotto features and more of his elaborate water sculptures among the mannerist terrace layout. But the construction was never completed due to the interruption by the 30 year war which saw the '

winter King' Frederick flee the country. The garden and palace buildings were greatly damaged - not for the first or last time. Lightning strikes in the 16th and 18th centuries and various wars all contributed to the deterioration of the site, despite intermittent attempts at reconstruction. In the modern era, restoration of the central building was carried out at the beginning of the 20th century and vestiges of de Caus's garden motifs and the remains of the palace ruins are now preserved.

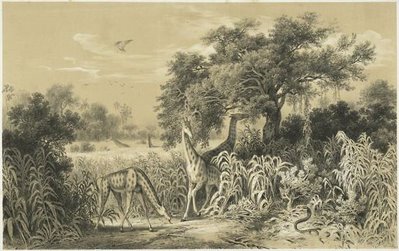

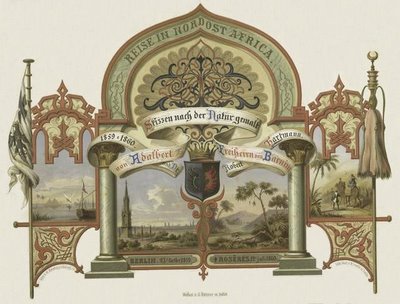

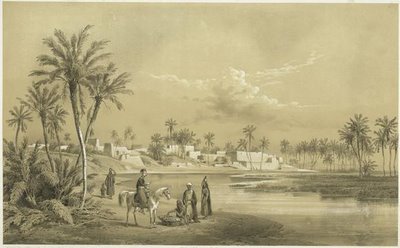

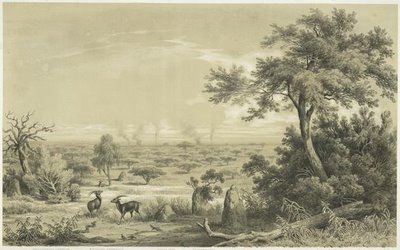

![Der blaue Fluss unweit Bedûs [Dâr Rosêres.]](http://photos1.blogger.com/blogger/1717/1584/400/Der%20blaue%20Fluss%20unweit%20Bed%3F%3Fs%20%5BD%3F%3Fr%20Ros%3F%3Fres.%5D.jpg)

![Zerîbah [Wohnung] des Melek Regeb - Adlân zu Hellet - Idrîs am Gebel - Ghûle.](http://photos1.blogger.com/blogger/1717/1584/400/Zer%3F%3Fbah%20%5BWohnung%5D%20des%20Melek%20Regeb%20-%20Adl%3F%3Fn%20zu%20Hellet%20-%20Idr%3F%3Fs%20am%20Gebel%20-%20Gh%3F%3Fle..jpg)

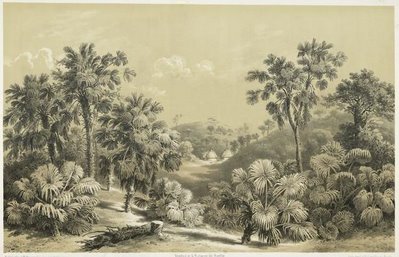

![Urdu [El - Ordeh]- Neu Donqolah, Den 28 sten Maerz 1860.](http://photos1.blogger.com/blogger/1717/1584/400/Urdu%20%5BEl%20-%20Ordeh%5D-%20Neu%20Donqolah%2C%20Den%2028%20sten%20Maerz%201860..jpg)

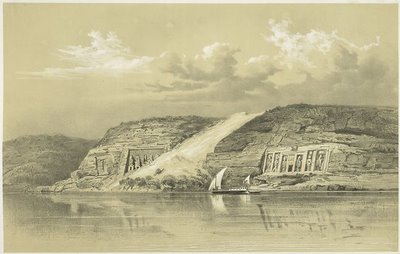

![Karane des Freiherrn Adalbert von Barnim Inderwuste des Batn - el -Hágar. [Nubien.]](http://photos1.blogger.com/blogger/1717/1584/400/Karane%20des%20Freiherrn%20Adalbert%20von%20Barnim%20Inderwuste%20des%20Batn%20-%20el%20-H%3F%3Fgar.%20%5BNubien.%5D.jpg)