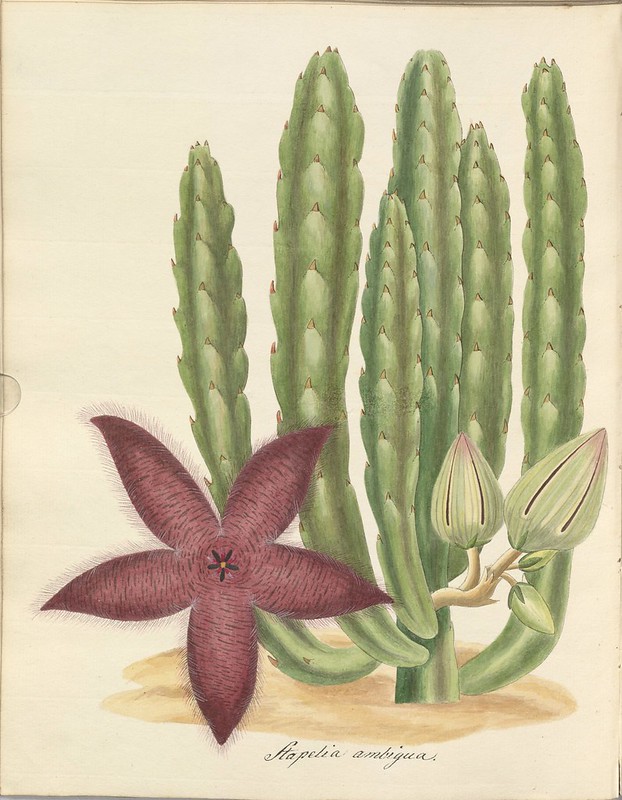

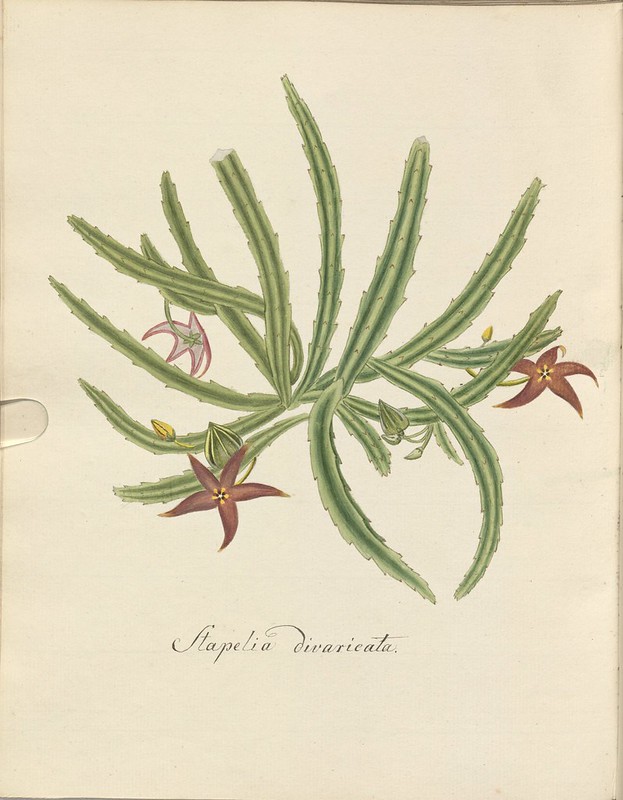

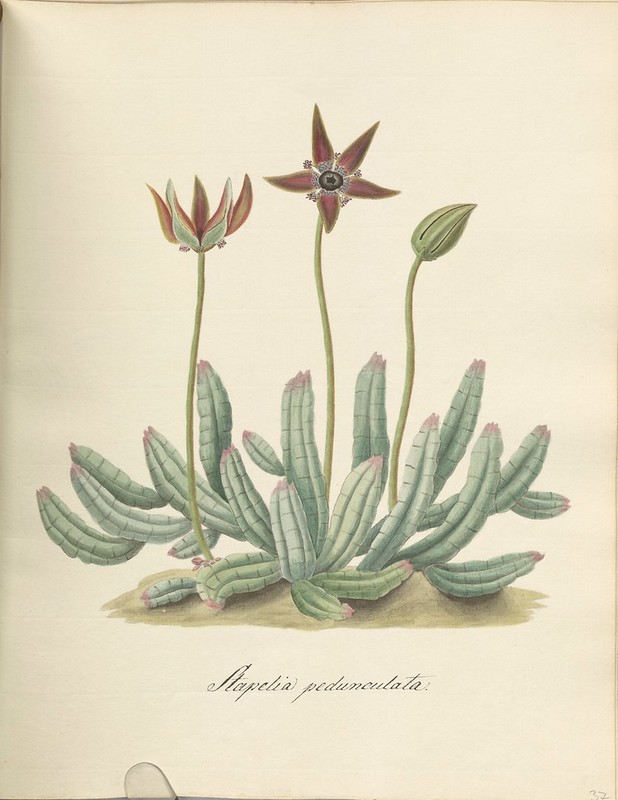

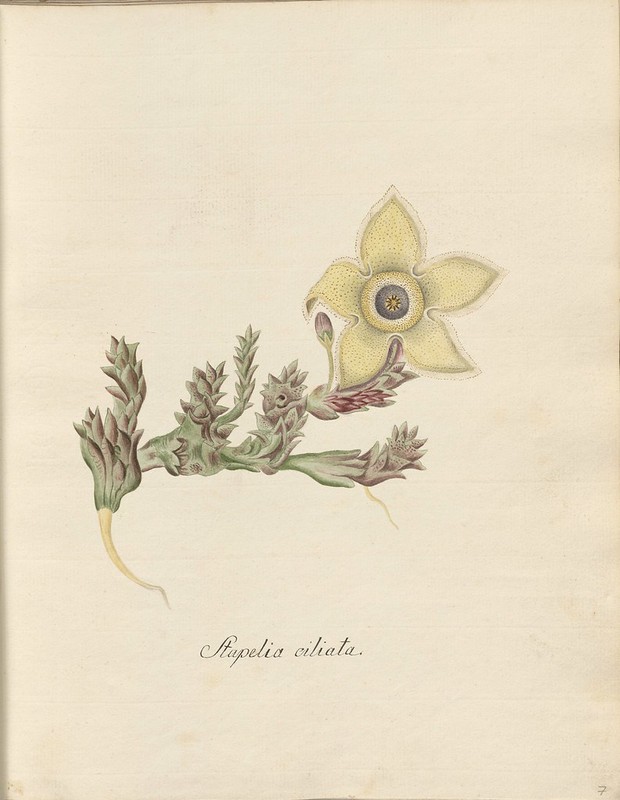

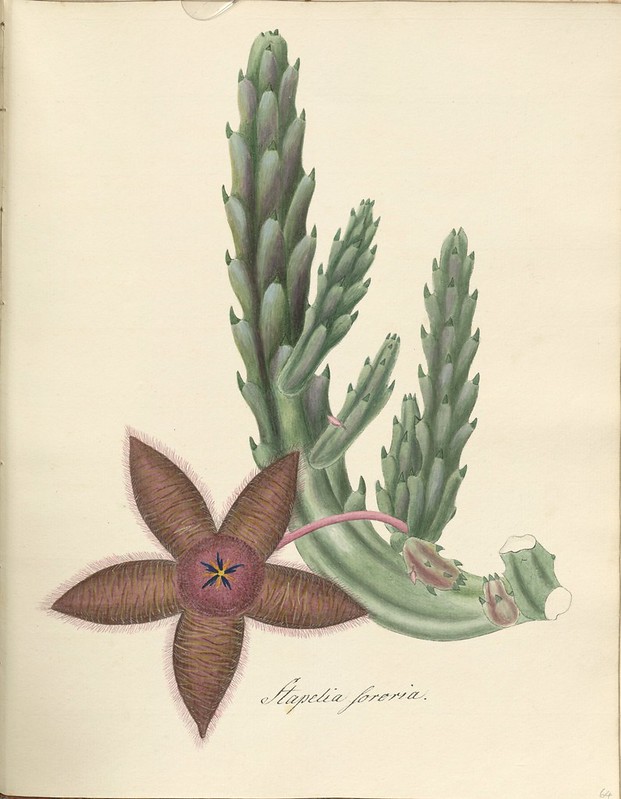

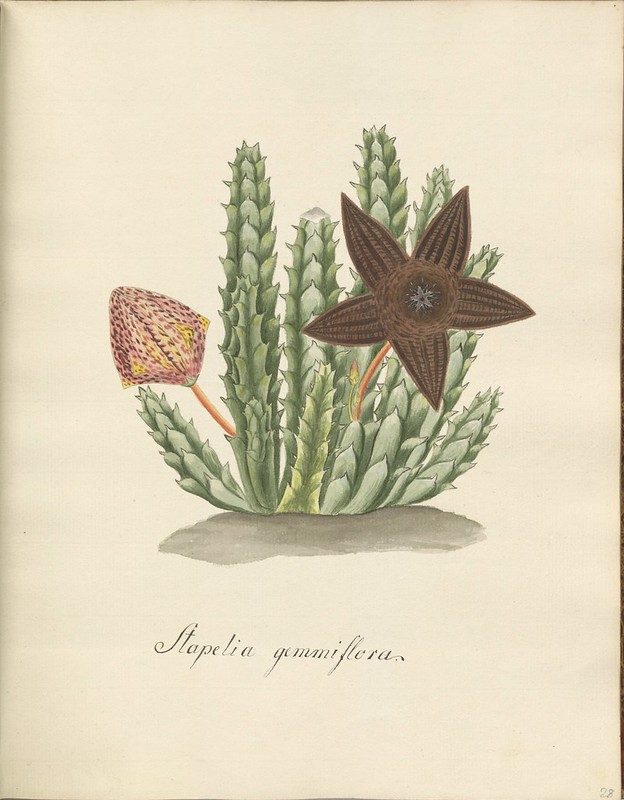

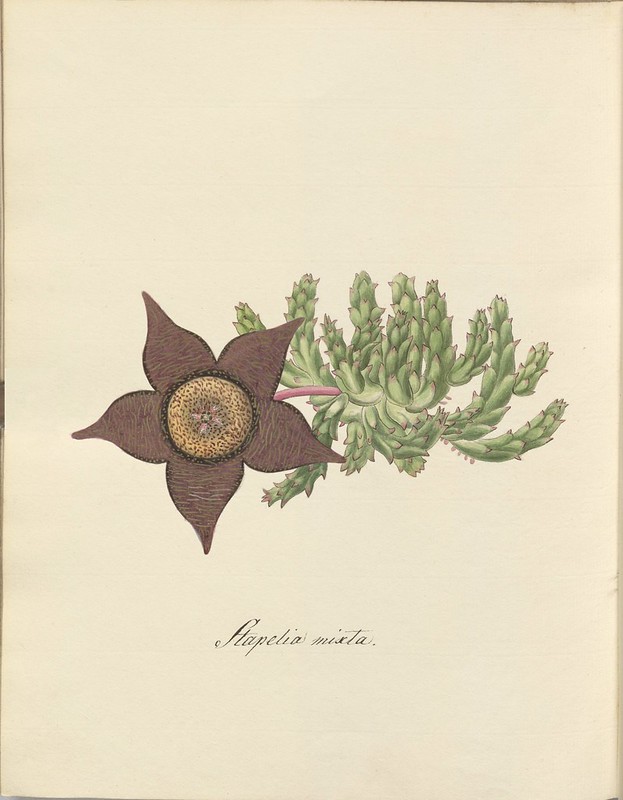

"[S]till enjoying, though in the afternoon of life, a reasonable share of health and vigour, I am now ready to proceed to any part of the globe, to which your Majesty's commands direct me. Many are the portions of it that have not yet been fully explored by Botanists - all of them are equal to my choice. To extend the science of botany, to enrich the Royal Gardens at Kew, and to obey your Majesty's gracious commands, are the only objects of ambition that actuate the breast of Your Majesty's most humble, most dutiful, and most grateful Servant, FRANCIS MASSON." (source)The genus Stapelia (tribe: Stapeliae, family: Apocynaceae^) consists of around forty low-growing, succulent plants from southern Africa. They may resemble cactus at times, but they are not related. The Stapeliads were a larger group back in the late 18th century when the illustrations below were first designed.

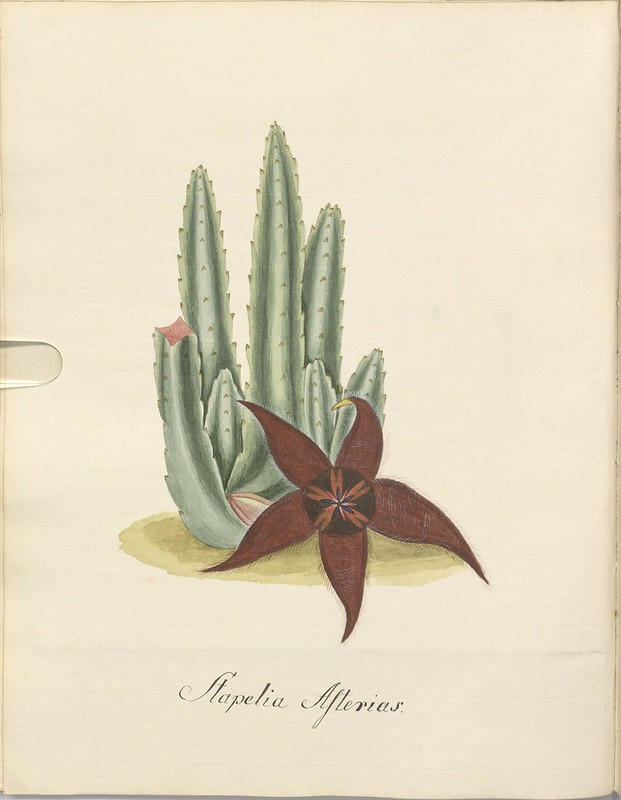

The main taxonomic characteristic in the 1790s was the extraordinary flower parts produced by most member species. In order to attract the blow flies that pollinate the flowers, many Stapelia species (and related/synonymous Orbea varietals) give off a stench of rotting flesh. The deceit is so effective that the flies lay eggs in the flowers, not realising there is no food to sustain emerging maggots.

"The hairy, oddly textured and coloured appearance of many Stapelia flowers has been claimed to resemble that of rotting meat, and this, coupled with their odour, has earned the most commonly grown members of the Stapelia genus the common name of 'carrion flowers'. [W]

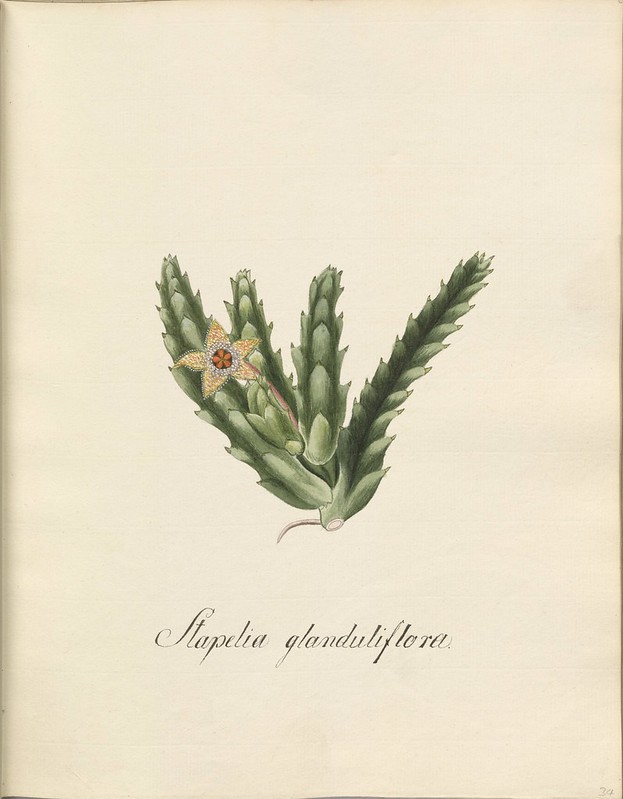

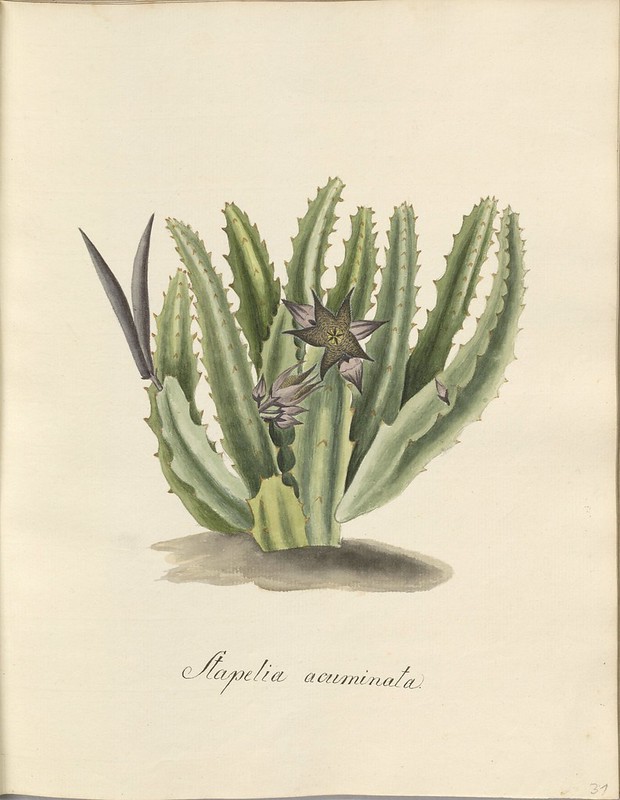

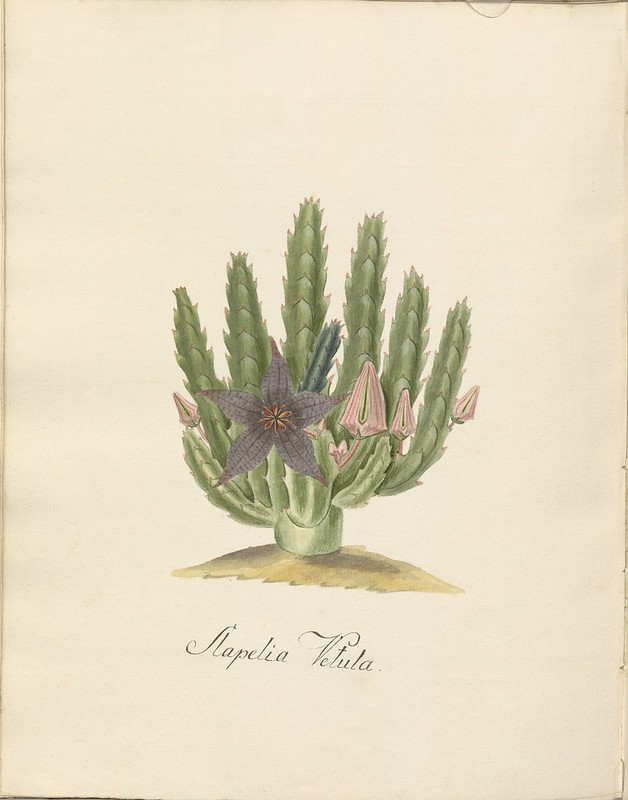

"[..] named by Linnaeus after the 17th-century botanist Johannes van Stapel, there are about 100 species taking their common names both from the flower shape and the smell of dead meat designed to attract flies as pollinators." [C]The original sketches for the 1796 book 'Stapelia Novae' are not seen below. Instead, in what may be a first for this site, - intentionally, at any rate - the hand-painted sketches from 1814 displayed here are reproductions based on the illustration plates published in a 1796 book, 'Stapelia Novae', by renowned plant-hunter, Francis Masson.

Customarily, the quest for illustrations to post here would centre around either the original drawings or their earliest appearance in published form. But only two original Masson drawings are said to have survived and the few random chromolithographic plates (that *I* have found^) from 'Stapelia Novae' online are of variable quality. However, the meticulous watercolour studies below by the young HL Wendland, after Masson's designs, are impressive in their own right.

These images are slightly colour-boosted and have been modestly background cleaned of spots and age-related stains.

Stapelia ambigua

Stapelia divaricata

Stapelia reticulata

Stapelia pedunculata

Stapelia ciliata

"I sailed for the Cape [with Cook aboard HMS Resolution] in the beginning of 1772, and remained there two years and a half. ... In the year 1786 I was sent out a second time to the Cape, and remained there near ten years, in which time I had opportunities more minutely to search that great tract of country; the various collections I have sent back from thence to Kew Gardens have been cultivated with ... much success... Two species only of Stapelia were heretofore described by botanists; the genus now promises a numerous harvest of species. In my various journeys through the deserts I have collected about forty, and these I humbly present to the lovers of Botany."

[Masson in the Introduction to 'Stapelia Novae'].

Stapelia gordoni

Stapelia glanduliflora

Stapelia asterias

Stapelia acuminata

Stapelia campanulata

Stapelia irrorata

Stapelia vetula

Stapelia sororia

Stapelia gemmiflora

Stapelia mixta

Famed botanist, Joseph Banks, returned to England in 1772 after a world voyage with Captain Cook. Banks was appointed Director of London's Kew Royal Botanical Gardens and was in close contact with his friend, King George III, a passionate gardener himself, who even maintained a residence at Kew. The King wanted to improve Kew's reputation in Europe and to that end, Banks sought out a Kew gardener to volunteer for a new role as Kew Gardens' first plant-hunter.

The successful applicant for the job was one Francis Masson (1741-1805) who had left Aberdeen in Scotland for a job as an under-gardener at Kew RBG when he was 19 years old. As the new plant-hunter, Masson was ordered by the Admiralty to join the first leg of Captain Cook's 2nd voyage of discovery aboard HMS Resolution which set sail for South Africa in 1772. This would be the beginning of his 33 year tenure as the official Kew Gardens plant-hunter (during which time he collected in excess of 1000 plants for Banks and Kew).

"Masson immediately embarked on a two month expedition into the interior, taking in the Stellenbosch and the Hottentot Holland Mountains. Sometimes working with Swedish Botanist Carl Thunberg and sometimes alone, Masson spent amost three years searching out new species of plants in South Africa. By the time he returned to Kew in 1775 he had sent back over 500 previously unknown plant species." [source]

"After exploring the Cape and working quietly at Kew for several years, Masson returned to plant hunting. In the late 1770s, he traveled to Madeira, the Canaries, the Azores, and Teneriffe before moving on to the West Indies. In the early 1780s, Masson sent back plants from Portugal, Spain, and finally North Africa. He endured numerous difficulties, including being caught in the crosshairs of a battle, a hurricane that destroyed all of his specimens, and raids by privateers. He began the winter of 1805 in Montreal, where he succumbed to the extreme cold of the Canadian winter at the age of sixty-five. By the end of his life, Masson had managed to introduce more than a thousand species of plants to Britain." [source]

"Although he did not have a strong education and published little, Masson established a solid reputation. [..H]e was intelligent, observant, and a born traveller. In the obituary of this “mild, gentle, and unassuming” man, the Montreal Gazette noted that “travellers who occasionally met him in remote countries . . . and men of science that knew his unremitting botanical labours and could estimate his talents, bear equal testimony of his merits and their writings incontestably evince his very uncommon success.”" [source]A 23 year old German from a family of botanists produced the illustrations of succulents seen above in 1814. Heinrich Rudolf (HR) Wendland (1791-1867) was doing an apprenticeship at Vienna's Botanical Gardens at the time and had an interest in exotic plants. He would pursue a career in botanical research and publish a number of papers on Acacia species. Wendland's watercolour sketches of carrion flowers were based on the chromolithographs published in Francis Masson's 1796 book. Wendland's collection of sketches is even bound with a hand-written reproduction of Masson's title page.

- The collection of HR Wendland sketches after Masson's designs are hosted by the Cultural Heritage of Lower Saxony portal. [direct to owner's site: Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Bibliothek]

- A full version of 'Stapeliae Novae: or, a Collection of Several New Species of that Genus; Discovered in the Interior Parts of Africa' by Francis Masson is available via Google Books, but the illustration quality is worse than terrible. There's possibly another version at the Royal Botanical Gardens in Madrid here, but I haven't been able to make any pages appear on my monitor with Chrome.

- A biography of Francis Masson constitutes Chapter 8 of 'The Zoological Exploration of Southern Africa 1650-1790' by L. C. Rookmaaker, 1989

- Francis Masson page (also) at the wonderful Dumbarton Oaks exhibition: The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century.

- Christie's auction entries: one, two.

- Francis Masson at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

- Masson biographies: one, two, three.

- Books featuring Masson & his 'Stapelia Novae'.

- PlantExplorers on Kew.

- Orbea pages: one, two.

- The Stapeliae at Stapeliads.

- HL Wendland at Wikipedia.

- A Masson-collected plant in 2009: *Ancient cycad, the King of Kew's Palm House, gets a new home*.

- Kew Royal Botanical Gardens.

- This post first appeared on the BibliOdyssey website.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Comments are all moderated so don't waste your time spamming: they will never show up.

If you include ANY links that aren't pertinent to the blog post or discussion they will be deleted and a rash will break out in your underwear.

Also: please play the ball and not the person.

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.