"[W]e are inclined to believe them to be produced by an evolution of the planet, just as on the Earth we have the English Channel and the Channel of Mozambique. [..]

Their singular aspect, and their being drawn with absolute geometrical precision, as if they were the work of rule or compass, has led some to see in them the work of intelligent beings."

[Giovanni Schiaparelli]

If we skip past some of the early contributors to our knowledge about the planet Mars -- Aristotle, Ptolemy, Copernicus, Galileo, Brahe, Kepler, Maraldi, Huygens, Herschel, Schroeter and doubtless other astronomers, all sharing the common handicap of relatively poor visual equipment -- we arrive in the second half of the nineteenth century, when the telescope's quality of resolution had advanced sufficiently, allowing for observation (and therefore mapping) of the Martian landscape.

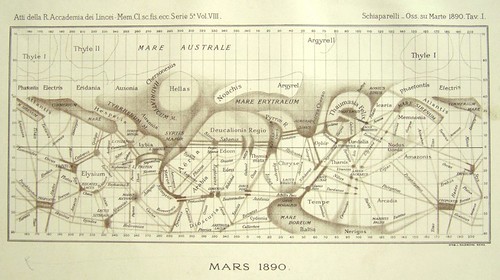

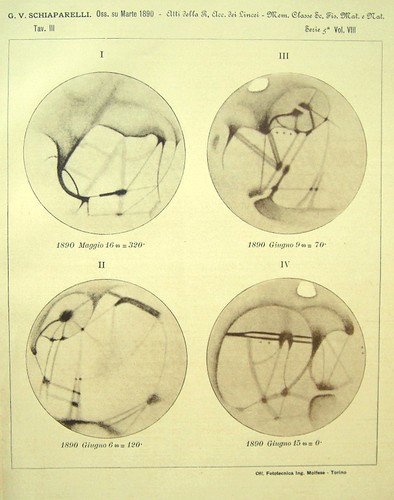

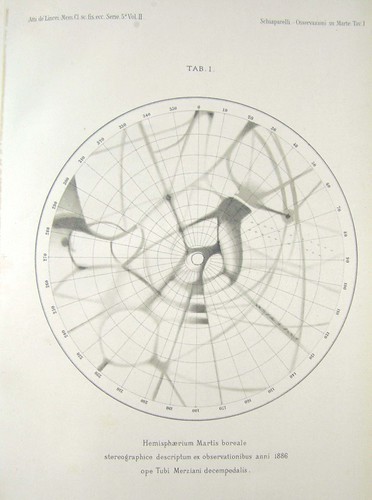

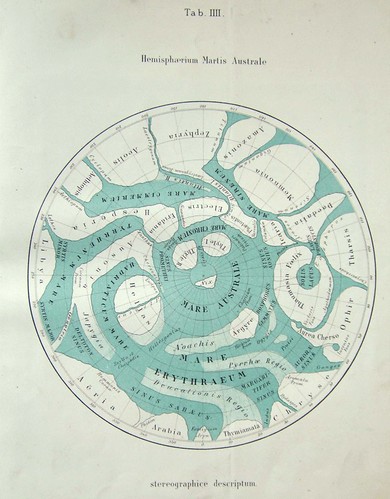

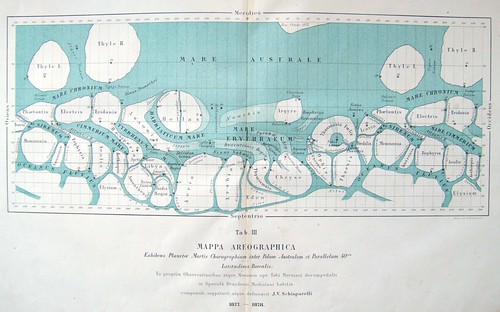

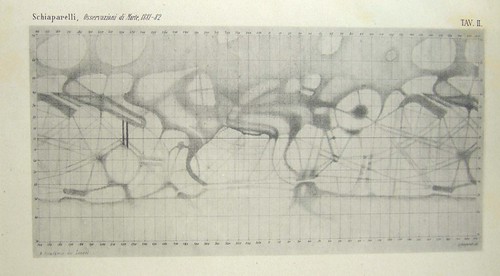

Chief among the early cartograhpers of Mars was Giovanni Schiaparelli (1835-1910), an Italian astronomer who worked at Brera Observatory in Milan for more than thirty years. In the late 1870s he produced an audaciously detailed map of Mars for which he had devised a nomenclature system to identify the newly discovered features. His system drew upon his knowledge of classical mythology, Greek and the Bible and thereby anointed the planet with "a set of romantic and wistfully evocative names".

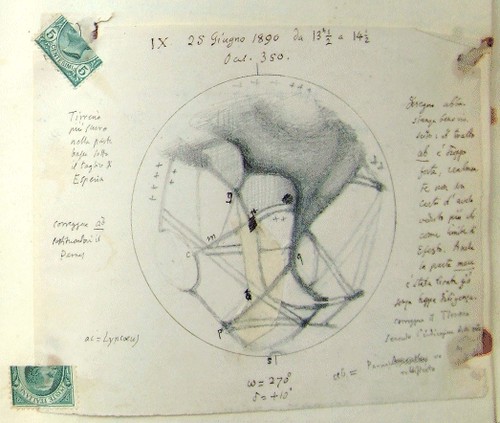

The myopic and colour blind Schiaparelli (neither of which, in all seriousness, hampered his renown as a meticulously observant astronomer) included in his map -- which he continued to augment all through the 1880s, and which served as the cartographic authority on the Martian landscape in planetary astronomy for two decades -- linear features that he saw criss-crossing the surface of Mars, which he referred to as 'canali'. This Italian word translates to English as either 'channels' or 'canals', and although Schiaparelli was implying the more naturalistic descriptor, 'channels', somehow 'canals' became the accepted terminology.

Whether or not there was any relationship between the construction of the Suez Canal at about the same time -- a decidedly artificial project -- and the way in which these martian canals added fuel to the romantic notion of there being intelligent lifeforms on Mars, is a matter for speculation. Nevertheless, and without going much further into the details, Schiaparelli inadvertently generated a most newsworthy phenomenon. Writings by the emphatic protagonist for the life on Mars idea, Percival Lowell (last picture above), were sufficiently noteworthy at the time to (apparently) provide inspiration for one of HG Wells' science fiction books.

Schiaparelli's (in)famous 'canali' turned out to be a kind of optical illusion caused by interactions between light, dust clouds that form in the martian atmosphere, the orbital location and background interference from the planet's surface itself. If a sketch is made of something that wasn't really there but you believed it to be there at the time, can you call the result abstract art I wonder? I guess so.

- The Brera Observatory website, 'Le Mani su Marte', presents pictures of Schiaparelli's diaries as well as lithographs of his maps and sketches: the origin of the majority of the above images.

- I *think* the illustrations are taken from an 1890s publication by Schiaparelli titled 'La Vita Sul Pianeta Marte' - this is the text in Italian at Project Gutenberg. [correction: this is Schiaparelli's original 1895 publication but not the source of the images. See Paolo's comment below (he ought to know).]

- The best background to all of this is the 1996 book by William Sheehan called 'The Planet Mars: A History of Observation and Discovery' which has been posted online by the University of Arizona Press. It's definitely worthwhile reading at least the first few chapters.

- Biography of Schiaparelli at the Internet Encyclopedia of Science.

- The second last image above (from 1873) is by Étienne Trouvelot (remember Trouvelot??) from the Annals of the Astronomical Observatory of Harvard College.

- The two wikimedia images above come from the Mars wikipedia article.