Under the surface of Voltaire's 1759 satirical novel, Candide, was a savage denouncing of the philosophical optimism promoted by many of his contemporaries that saw all disasters and human suffering as part of a benevolent, cosmic plan. In this picaresque work, the eponymous hero travels the world and witnesses appalling events but is forever guided by the philosophy of his tutor, Pangloss, that everything is as it should be, that it is "the best of all possible worlds."

"This idea is a reductively simplified version of the philosophies of a number of Enlightenment thinkers, most notably Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz. To these thinkers, the existence of any evil in the world would have to be a sign that God is either not entirely good or not all-powerful, and the idea of an imperfect God is nonsensical.If the ideas of German polymath philosopher Liebniz are the target in Voltaire's gunsight, the person upon whom the character of Pangloss was actually modeled is Noël-Antoine Pluche.

These philosophers took for granted that God exists, and concluded that since God must be perfect, the world he created must be perfect also. According to these philosophers, people perceive imperfections in the world only because they do not understand God’s grand plan."

Pluche was an ordained Abbott and Professor of Rhetoric and Humanities in Rheims. His most famous work was Le Spectacle de la Nature, ou Entretiens sur les Particularités de l’Histoire Naturelle, Qui ont Paru les Plus Propres à Rendre les Jeunes-Gens Curieux, et à Leur Former l’Esprit - 'The Spectacle of Nature, or Talks on the Characteristics of Natural History Which Appear Most Specific to Make Young People Curious and to Form the Spirit in Them'.

Le Spectacle de la Nature was first published in 1732 [I think the final of the 8 volume series came out in 1750] and is more properly categorized as a natural theology rather than a natural history work, per se. In this regard it seems to be peculiar to its time in both anticipating Diderot's L'Encyclopédie [1751 to ~1770] by innovatively presenting the known science and useful technology of the era, but by also portraying the natural world as being anthropocentric: everything exists on earth - provided in God's master plan - so as to be useful to humankind. It's obviously this latter point of view held by Pluche that Voltaire was attempting to skewer.

To be fair to Pluche it is difficult, even with hindsight, to be immediately dismissive of his incredibly popular opus. He was primarily motivated by a wish to be a good educator and his chief aim with Le Specacle de la Nature was to popularise science. It seems to me, after reading around a lot more than I originally intended, that Pluche succeeded in both these endeavours. And he managed to do so within a theological framework - that one ought to pursue science as a religious imperative or duty.

It is a wonder the conservative forces behind the so-called intelligent design theory of today have not adopted Pluche as their patron. Looking back, Pluche appears to have been a great and enlightened thinker (although not always perhaps in keeping with the thinking of the Enlightenment) and an important contributor to education and science on the road from the middle ages to the modern world. I'm a little surprised he is not very well known. He would simply be regarded as conservative were he alive today.

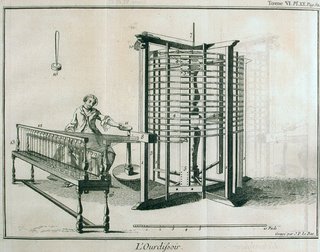

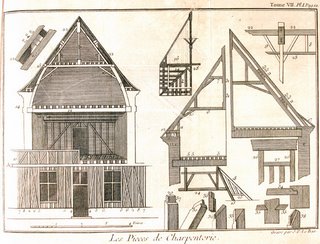

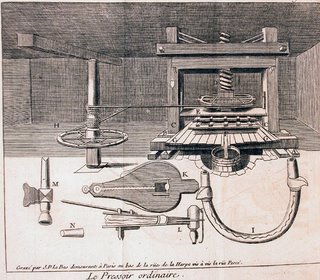

Jacques-Philippe Lebas prepared about 200 engravings to accompany Pluche's text, which incidentally, was presented as a conversation between four fictional characters, one of whom of course played the role of knowledgeable teacher. Through the books they talk for instance about the insects, plants and animals and the technologies and machines that can be employed so humans can benefit from them; all things to do with the sea and ships and fishing; a review of astronomy (Pluche was an ardent supporter of Newton), mineralogy, optics and horology &c; the history of society and importance of education and a final historical investigation of religions.

That's a very brief outline - this was an encyclopedia by any other description. The language made the science more accessible to people and the engravings would just about allow this work to be included in the theatre of machines genre (probably not realllly). There were 57 editions in France alone and it was translated and published across Europe for more than 100 years. I was particularly attracted to this work by the number of areas of endeavour Pluche managed to straddle and how well he appears to have charted his course between the often competing interests of education, science and religion. He did manage in fact to have the best of all possible worlds, t'would seem. [No library was injured in the making of this entry which took more than 24 hours to prepare one way or another, and although all care was taken, as usual, nothing should be taken as authority.]

- About 100 of the LeBas plates from 6 of the volumes of Le Spectacle de la Nature are available online from Biblioteca Comunale Forteguerriana via the [wonderful] F.Datini database. The above images were loaded at full size so click for larger versions.

- A translation of the french wikipedia entry on Pluche [original].

- This translated german page which gives a brief overview of the contents of Le Spectacle.

- A translation of a Pluche biography.

- Another short biography of Pluche which gives a bibliography of his published works.

- Candide by Voltaire: study guide and etext.

- I don't know the origin of the commentary at this ebay site but it gives a reasonable account of Pluche's place in the 18th century.

- Pangloss and the Abbé Pluche © 2003 by Eric Palmer - a 10,000 word thesis [.pdf]. It's a long but worthy read, although there is a fair sprinkling of french throughout that makes it difficult {for me anyway} to scan easily.

1 comment :

Newly uploaded versions at Uni. Strasbourg.

Post a Comment

Comments are all moderated so don't waste your time spamming: they will never show up.

If you include ANY links that aren't pertinent to the blog post or discussion they will be deleted and a rash will break out in your underwear.

Also: please play the ball and not the person.

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.