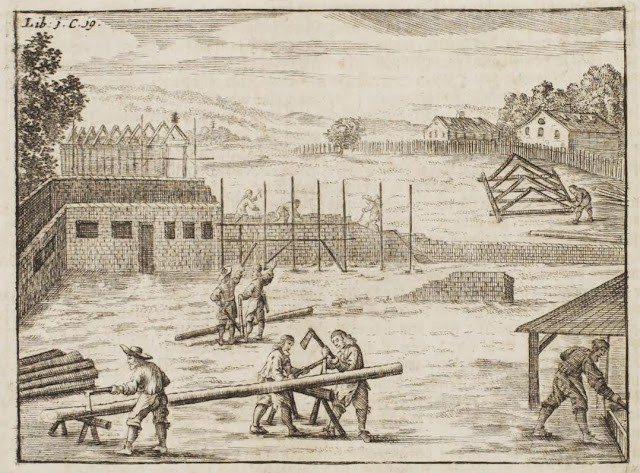

From beer barrels to blood-letting to breeding, this 3-volume proto-encylopaedia of agriculture and homestead management had the landed gentry in Austria/Germany in the late Baroque period well-covered for farming information. 'Georgica Curiosa' by Wolf Helmhardt von Hohberg was first published in 1682. Editions were released in the following decade of both two and three volumes in length and they all included copious numbers of engravings to illustrate the extensive text.

The full title of the work (probably just one of the volumes) approximates as follows:

" Georgica Curiosa -- that is, a complete and clear education report about living a noble, country life.

Covering the german countryside and home economics /

Here and there mixed with rare inventions and experiments /

All embellished with a large number of beautiful copperplates /

In two marvellous Parts - each divided into six books /

Presented in such a way that in the

FIRST PART:

The workings and holdings of country estates /

How christian house-fathers and house-mothers act during their work-life inside and outside of the house /

In every situation and during seasonal changes, throughout the whole year /

In each chore and situation in the house and on the field /

In their behaviour towards others /

And how to best arrange wine and fruit for the kitchen, and the use of medicinal and flower gardens /

How to keep them viable and how to profit from them is also included

IN THE OTHER PART

How to organize all of farming in the easiest, lightest and most useful way /

Be it in the breeding and training of horses, or how to care or breed and enjoy cattle /

How to obtain bees' wax, the silk of worms - from which to make a profit /

How to create all kinds of fountains, cisterns, canals, ponds, pools, dams, brooks, fish nurseries, and other waterworks /

How to plant, maintain and improve the manure and any kind of farm field with different types of game and fowl: all this is explained.

Brought to light by a member of the honourable fruitbearing society "

Wolf Helmhardt von Hohberg (1612-1688) was a soldier in his early adult life, attaining the rank of Captain by the time he was 30. He left the army soon after and took up residence at his family's land holdings in Thaya, ~Czech/Austria. He became something of an informal scholar (supposedly to while away the winters), educating himself in ancient and modern languages, poetry, literature, history and agriculture.

He fled his farm for Regensburg (SE Germany) in ~1660 due to the persecution of Protestants and he remained there until his death. He was a well respected citizen and a highly decorated member of the exiled Austrian nobility. Though his main love was agriculture, von Hohberg published a number of epic poems, inspired by figures such as Virgil and Aristotle. One of these works apparently told the story of a Byzantine superhero percursor to the Hapsburg dynasty(!?)

Von Hohberg is best remembered for his contributions to agricultural and rural studies. The images above come from an exhaustive and pioneering review of both farming practises and wholistic rural living.

"A rare three-volume edition of Hohberg's major work on agriculture, considered a forerunner of the specialized agricultural encyclopedias of the eighteenth century, and which also covers fruit-growing, gardening, viticulture, manufacture of glass and soap, mining, food, spices, cattle breeding, horses, forestry, human and veterinary medicine, hunting, fishing and beekeeping. The particularly rare third volume ends with a cookery section titled 'Bewahrtes Wohleingerichtetes Koch-Buch'." [Source]That basic description leaves out an important dimension of von Hohberg's publication (which itself began life as an extended poem!). Beyond the practical and academic concerns, von Hohberg was trying to teach the farming community how to lead a dignified life. His volumes lay out the importance of the patriarchal system and appropriate subordination to the paterfamilias*; how people might best control their inner 'passions'; the varied economies of a household and holdings; the nature of just and unjust earnings; as well as the rightful place of religion and prayer in a good person's life.

I noted in passing that 'Georgica Curiosa' supposedly took von Hohberg more than 20 years to write, which gave him time to do both a comprehensive review of all the agricultural literature available, plus survey a wide section of the Regensburg rural community and surrounds to document the range of farming activities and best practices used by families, workers and the like. It also appears that his early epic poetry was received with less enthusiasm by his contemporaries than von Hohberg would have liked. It was apparently dismissed by the 'serious' folk as some sort of fanboy ravings by a Virgil-wannabe, who only ended up as a member of a fruit-bearing society for his 'epic' troubles. Or so the story goes..

- 'Georgica Curiosa' (1682) by Wolf Helmhardt von Hohberg is available online from Heinrich Heine Universität Düsseldorf (click 'Overview' for thumbs) - to be honest, I'm not totally certain how much of the series is on the website [eg.] but it's probably only the first volume [contents]. It was a 3-volume publication but was released at least once in only two volumes. In any event, it's a very large work whose ample number of (what might individually and charitably be called serviceable) engravings, together form a great visual farming record of the period. I like being surprised in this way. You see one engraving and shrug, but after 30, 50, 100+ illustrations of this type .. they can become fairly hypnotic, and much more informative, even beautiful in their own way, en masse.

- A couple of resource links (in German): Wolf Helmhardt von Hohberg - Wikipedia :: Deutsches Museum = best link overall.

- Worldcat entries for Wolf Helmhardt von Hohberg.

- Amazon search mentions of Wolfgang Helmhard Hohberg.

- ADDIT: ULB Sachsen-Anhalt features digitised copies of von Hohberg's works and appears to have all three volumes from the 'Georgica Curiosa' series available online.

- Thanks very much Jeanne!

- This post first appeared on the BibliOdyssey website.

The Foreword to 'Georgica Curiosa' goes something like this:

"I never thought of writing about economics, but after the original 'Georgica..', many of my reader friends told me that such an instructional work would be better as prose than as poetic verses. I didn't do that until I came to Regensburg, where I finally found the free writing time.

Everybody knows some parts of what I write about, so I will try to do it wisely, like Plutarch in his Feast for the Seven Wise (Greek) Men, where Periander asks which domestic economy is the best, and Solon answers, one where no stolen goods or land is to be seen, that you can keep without mistrust and give without regret. Then come the opinion of the other six greeks... where there is more love than fear, where you have all you need and don't desire the unnecessary, where you only do sufficient as is necessary, etc.

Many writers have tried this. It is a long list: first, the Greeks and Romans and Phoenicians. Then Italians, Frenchmen, Spaniards (one of them is better at prayers then at economy). Then the Africans, translated from latin to arabic by the Granadian scholar Mansor. Then a Jesuit from Poland, some Flemish. And quite a few good works from England.

The first german work is from Kaiser Konstantin IV and then, the best known is the 'Calendarium Perpetuum' by Johannis Coleri, in 20 volumes. A few more and I almost forgot, Georg Andres Böckler, who in 1678 edited a useful House and Field School, and more followed. But some of them have stole their writing word for word from others, and are not worth being remembered (and, in fact, should be punished). Others manuscripts have helped me too. [..]

About no part of the book have I found works written in so many languages then Gardening. (Then [von Hohberg] thanks the people who made the etchings, his friends, particularly some doctor in Regenburg who lent him a lot of books. *But since Economy is one of the most all-encompassing sciences, one can't hope to have made a perfect work... Economy is like an ocean, with so many rivers coming into it.*

The order of the work is in two books, each divided into six, which makes 12 books altogether. Everything is included in named chapters, which makes perusing easy. The people who don't like the poetry should skip it and go to the more explicit parts. But I left some poetry in it, so as not to divide the sweet/aesthetic from the practical. If some wish to argue that I only speak about the climate in Austria, that the book can't be used for the whole of the Roman Kingdom, I'll say that, at least most chapters are universal, and in one chapter you'll find some charts that can help to calculate the differences between places.

Here's hoping for moderation in my readers.. "