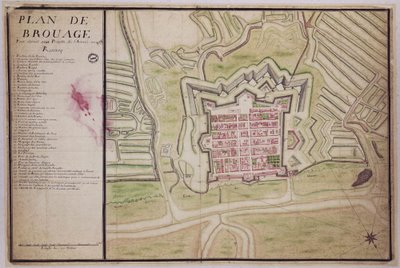

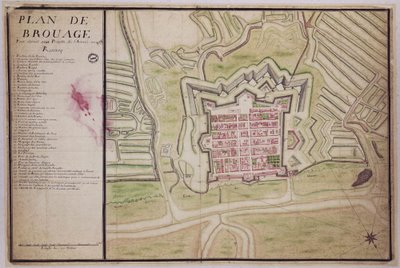

'Map of Brouage, to serve for the projects of the year 1729'

"In the age of discovery, the French ports along the Atlantic shoreline and the English Channel were naturally attracted to the New World. From Bayonne to Dieppe, by way of the salt-rich ports of Saintonge, such as Brouage (birthplace of Samuel de Champlain), ships travelling the sea routes with North America supplied all of France with cod."

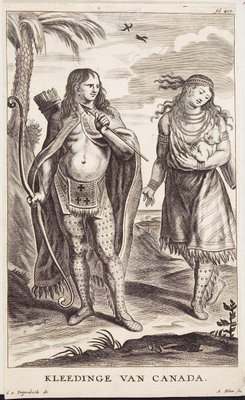

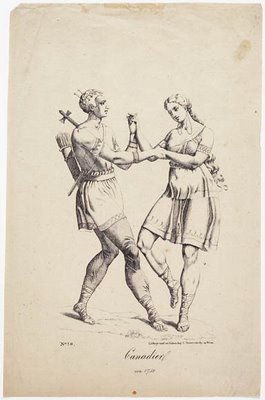

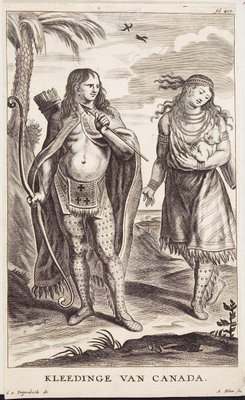

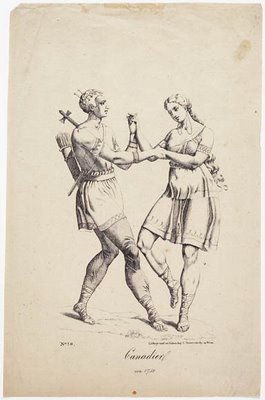

'Costumes of Canada (

c. 1650)'

"From the start, the Aboriginal peoples of North America made themselves essential to the French as suppliers of pelts and furs, and played a key role in the economy of New France. They also took part in the conflicts between the French and English in North America.

The arrival of the immigrants — with evangelization, attempts at cultural assimilation, technical progress and diseases brought from Europe — resulted in a profound upheaval in the way of life of the Aboriginal population. Because their culture was oral, it was through accounts written by missionaries and explorers, and the iconography they used to describe them, often not based in reality, that Aboriginal traditions and language were revealed."

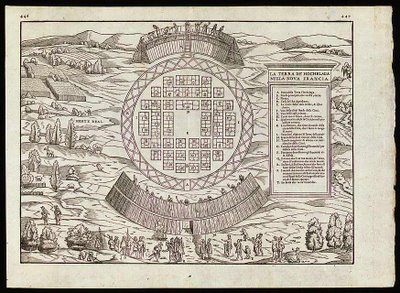

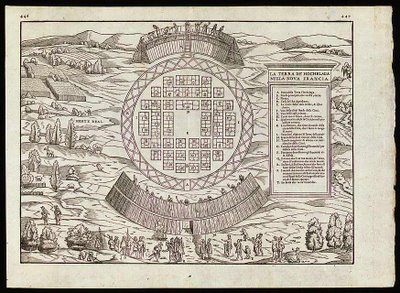

'The land of Hochelaga in New France by Giovanni Battista Ramusio, 1565.'

"In 1535, Jacques Cartier visited the Iroquois village of Hochelaga, the future site of Montréal, and described it in the account of his second voyage. This woodcut, published in Venice, is the first printed plan of an urban area in North America."

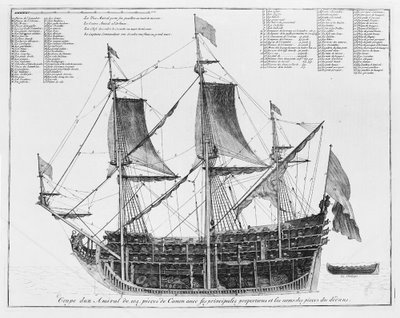

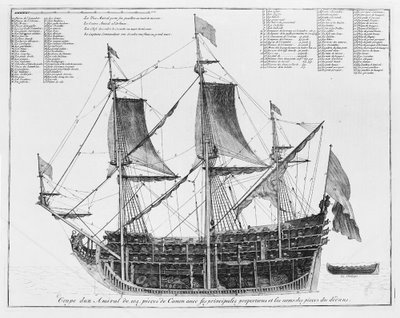

'Cross-section of a 104-gun flagship giving the main dimensions and

the names of the interior compartments], from 'Le Neptune françois ou Atlas nouveau des cartes marines', by Pène, Cassini et al., 1693'

"In the 15th century, fully rigged sailing ships became more common than galleys because of their higher waterline, rounded form and the complex rigging of their two or three masts. However, they were heavy and slow. French shipbuilding, long a craft-based enterprise, improved in the 18th century thanks to the contribution of specialized engineers, and it became possible to build ships with increased tonnage."

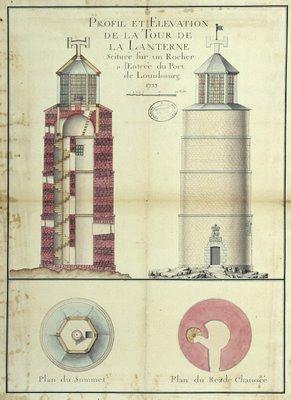

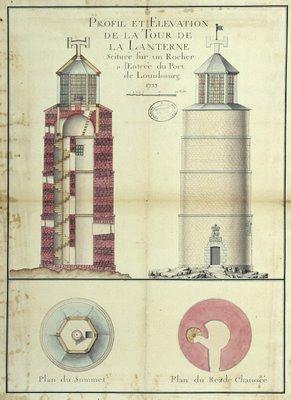

'Louisbourg Lighthouse 1733'

"Cape Breton Island became Île Royale [and] [b]eyond its defensive role, Louisbourg soon became an important port, and the hub of exchange for France, the West Indies and Canada. The fortified town included half the population of Île Royale, about 4,000 in 1750, and a large proportion of soldiers were quartered there in barracks. The English took control of Louisbourg in 1745, but Île Royale was given back in 1748. It fell permanently to the English in 1758."

'The Governor's House and St. Mather's

Meeting House, Halifax (Nova Scotia), 1764'

"As a major confrontation brewed between France and England over control of North America, Acadia became of vital strategic importance. England sought initially to reinforce its military presence in the region. It founded the town of Halifax in 1749 and introduced settlers throughout the territory. The Governor of Nova Scotia, Edward Cornwallis, demanded that Acadians swear unconditional allegiance to the British Crown, in order to eliminate any possibility of neutrality. In their petitions to the Council of Nova Scotia, the Acadians refused to take such an oath, which could oblige them to take up arms against France, but they did confirm their loyalty to the King of England.

The members of the Council, under President Charles Lawrence, rejected any possibility of tolerance towards the Acadians, and on July 28, 1755, decided to expropriate and expel them. Approximately 7,000 Acadians were thus assembled and sent by ship to the English colonies on the Atlantic coast; by 1762, another 2,000 to 3,000 had suffered the same fate. Sickness, epidemics, difficult voyages and harsh exile conditions, which were the result of this deportation, led to many deaths."

'Canadians of 1750' (c. 1815-1835)

"From the 16th century, the naked "Indian" wearing a feather headdress appeared in European iconography. Artists could base their works on the several Aboriginal people brought back by the explorers to be shown as curiosities at court and for entertainment in shows. The image of Aboriginal peoples formed by Europeans was largely the conception of artists who had never been to America. The European attitude was divided between the image of a "noble savage," virtuous and pure, and that of a barbarian in need of civilizing."

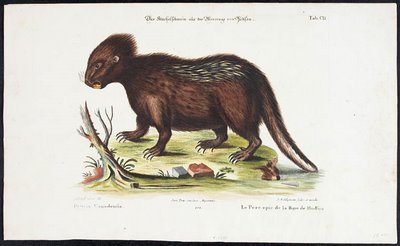

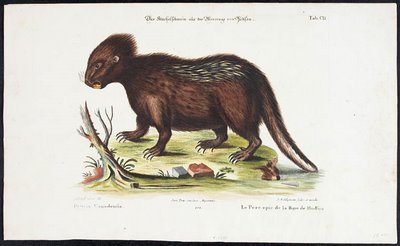

'Hudson Bay Porcupine 18th century'

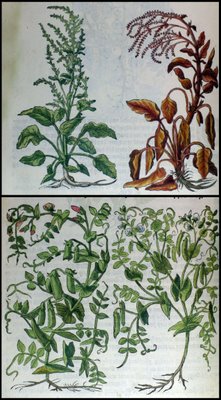

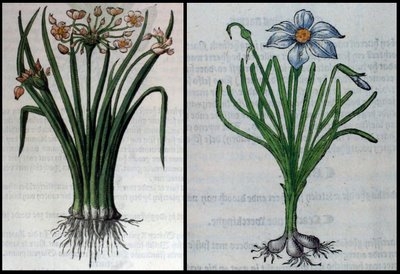

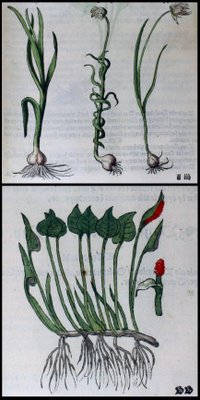

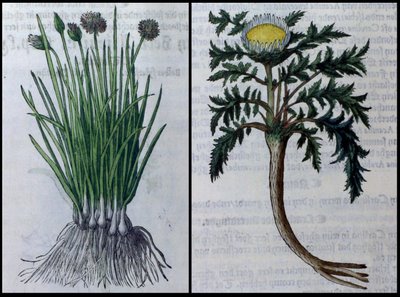

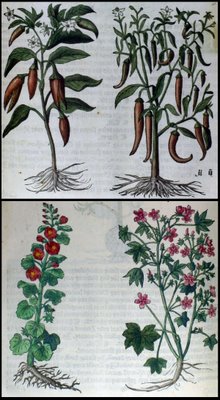

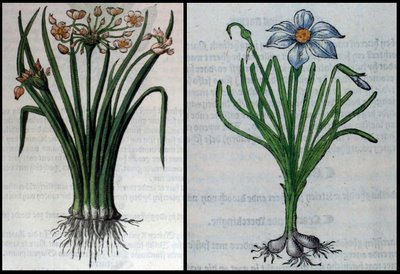

"In addition to cartographic elements, descriptions of places and ethnographic observations, travel accounts often included a brief account of the flora and fauna. The earliest descriptions are approximate. [..]

All types of animals were of interest, but particularly those noted for their hides and pelts. Starting from the first voyages, specimens were brought back to Paris for the king's garden."

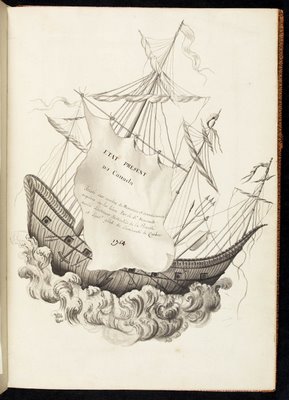

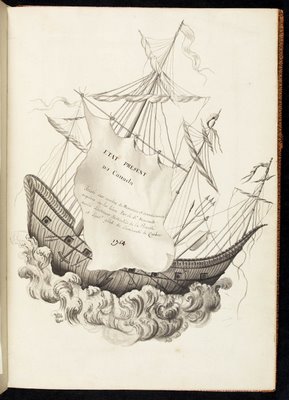

'Present state of Canada based on numerous Memoirs and

knowledge acquired in the field by Seigneur Boucault, Former

Special Lieutenant of the Provost Court and Lieutenant General

of the Admiralty of Québec], by Nicolas-Gaspard Boucault, 1754.'

"An organized society did not take shape until the creation of the royal colony in 1663, with the establishment of an administration by the Church and the monarchy, the arrival of new immigrants (who brought with them the traditions of various provinces of western France), and the development of urban communities centred around hospitals and educational establishments. [..]

The social structure in the colony was less rigid than in France, and before long, individual status became less a matter of birth than of merit, talent and usefulness. The spectrum of social positions narrowed, and the population gradually integrated characteristics that reflected the influence of the land, the climate, and contact with the Aboriginal peoples. During the 18th century, most of the colony's inhabitants defined themselves as Acadians or Canadians"

New France - New Horizons: On French Soil in America.

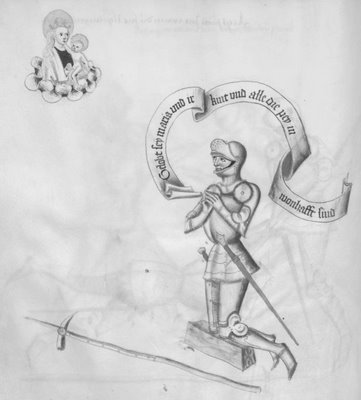

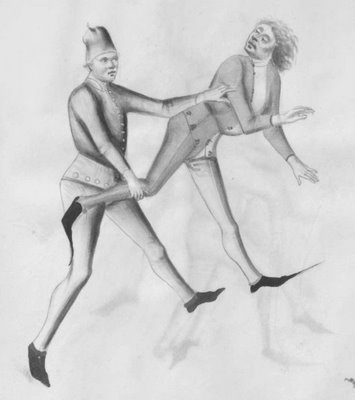

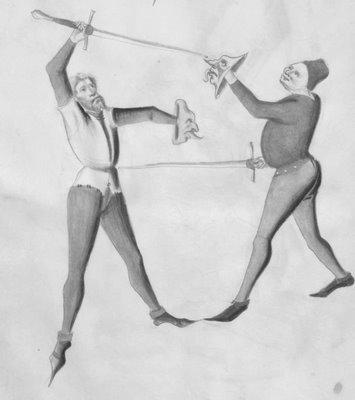

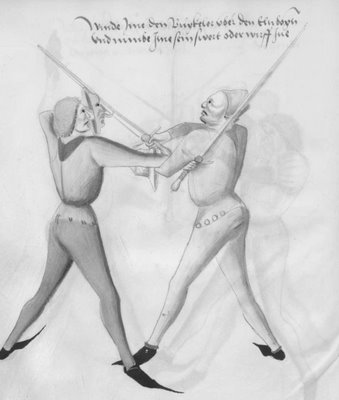

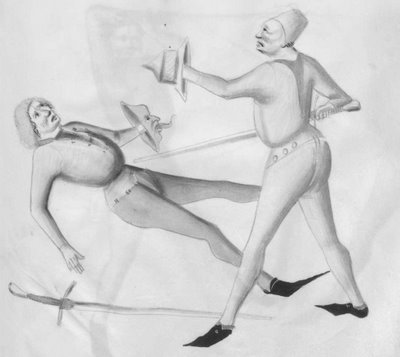

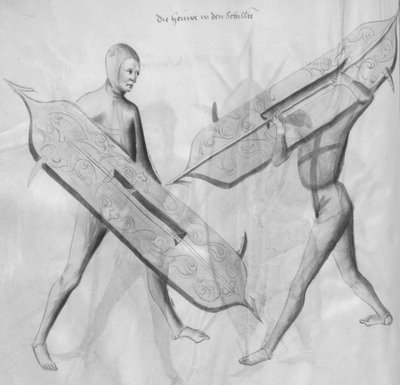

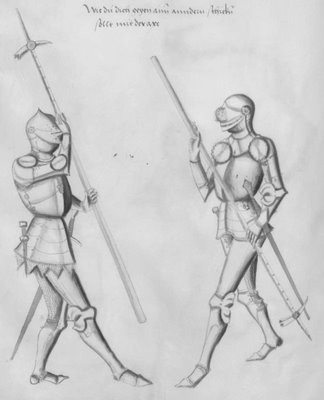

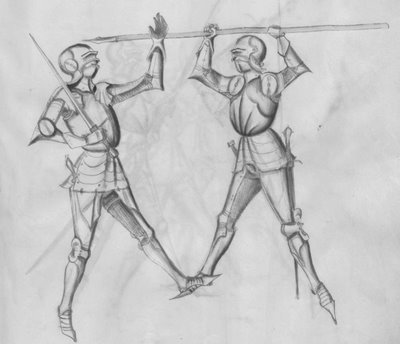

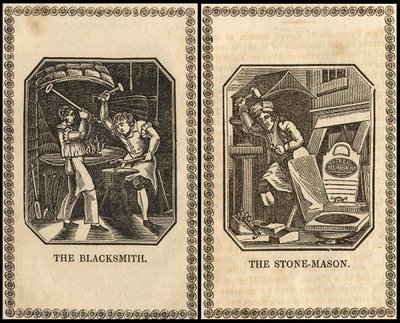

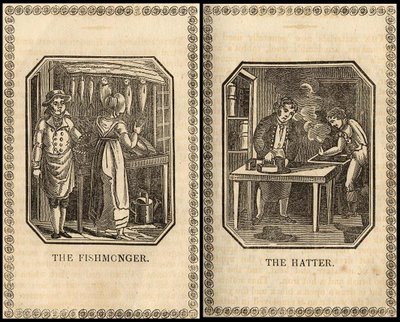

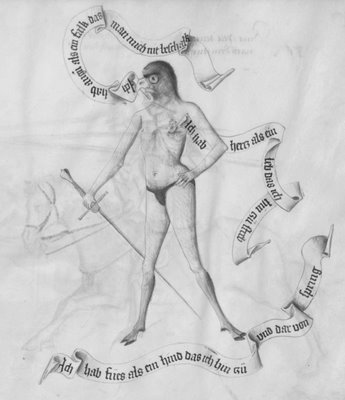

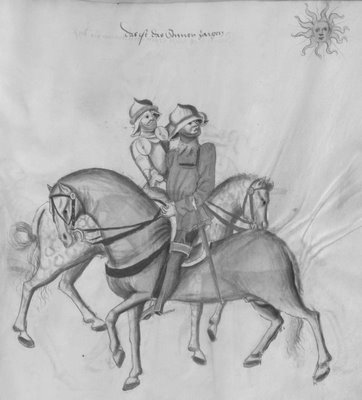

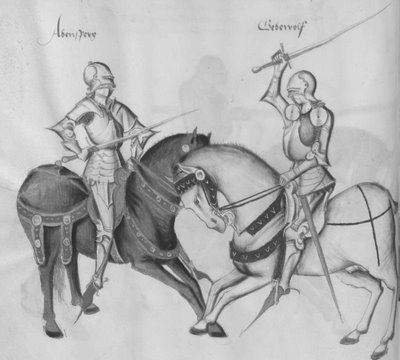

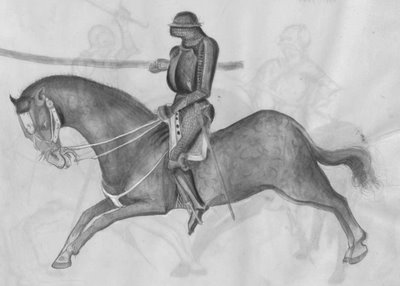

'Kunst des Fechtens' (the Art of Fighting) refers to the traditions and written manuals associated with the german school of combat techniques in the middle ages. Among these Fechtbücher (fight manuals) is the untitled fechtbüch of Paulus Kal, depicted above and in the previous post, which is online at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. (produced sometime before 1479)

'Kunst des Fechtens' (the Art of Fighting) refers to the traditions and written manuals associated with the german school of combat techniques in the middle ages. Among these Fechtbücher (fight manuals) is the untitled fechtbüch of Paulus Kal, depicted above and in the previous post, which is online at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. (produced sometime before 1479)