"In 1401 a young man named Michael of Rhodes joined the Venetian navy as a lowly galley oarsman. Over the next four decades, he sailed on more than 40 voyages and took part in five major sea battles, rising through the ranks to become a trusted galley commander.

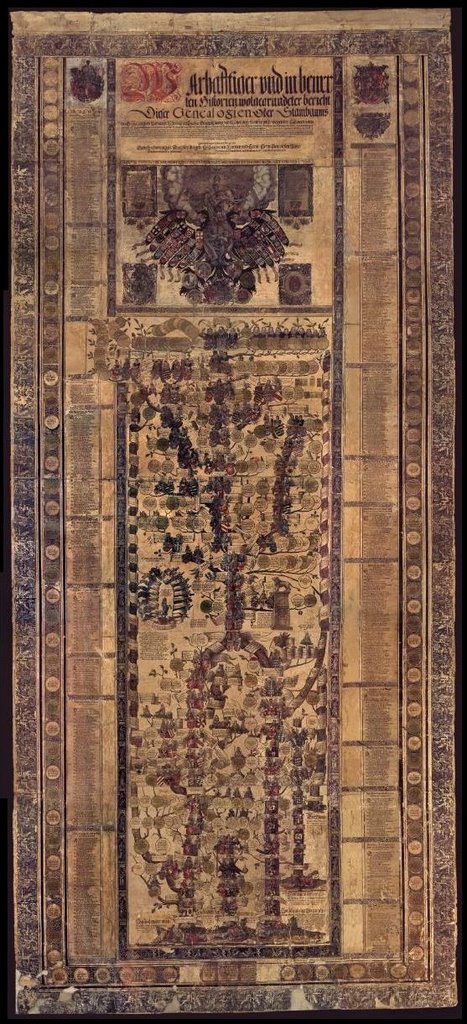

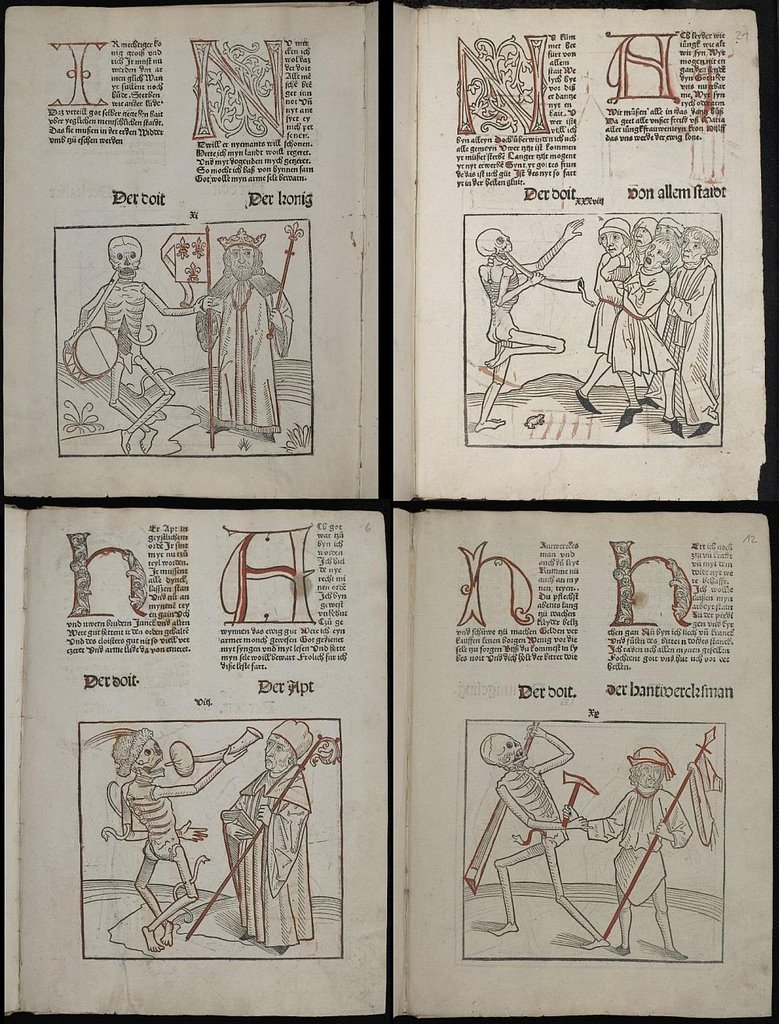

Michael documented his life and knowledge in a remarkable manuscript. Only recently rediscovered, it chronicles Michael's service record and includes more than 200 pages of commercial and calendrical computations, a beautifully illustrated section on astrology, some of the earliest surviving portolan aids to navigation, and the world's first known treatise on shipbuilding."

"The Michael of Rhodes manuscript was lost for 400 years until it resurfaced in 1966 and again in 2000, when it was made available to the Dibner Institute for the History of Science and Technology for study" {I recommend the non-flash version -- that way you can see the larger images} The commentary is excellent.