"From the 1530's onward there is a slow but steady increase in the number of printed books on technology, and by the latter third of the century, print had become a suitable medium both for descriptive works and for presentation of technical innovations, as well as discussions of the significance of technology in general. This movement toward a fully public medium completed the transformation initiated with the shift toward manuscripts in the fifteenth century.

Technology, which had once been nearly the exclusive possession of a particular craft group, was now being displayed and discussed before a wide audience of educated, but unspecialized readers. By 1600, technical information was being transmitted through three main channels: the older, oral medium of the craft group; the manuscript which circulated among interested parties; and the printed work intended for a "semi-popular," moderately learned, lay public. With minor modifications, this situation persisted until the late eighteenth century and the rise of schools of engineering. Its final transformation came only in the following century with the rise of industrial societies and the beginnings of mass secondary education."

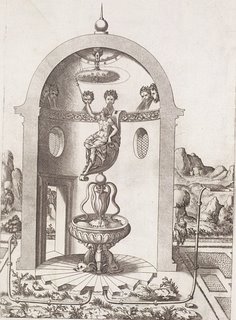

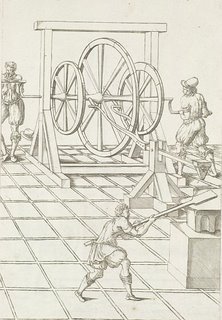

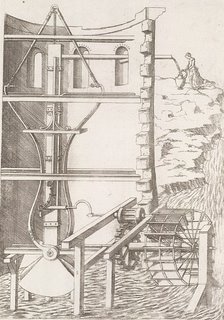

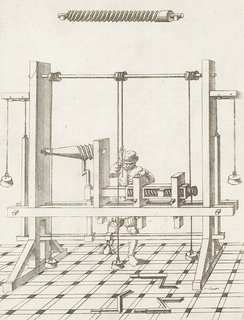

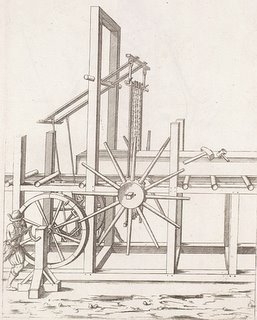

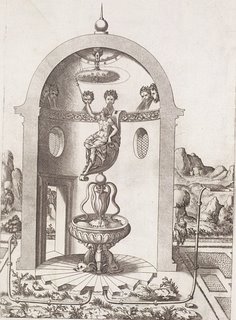

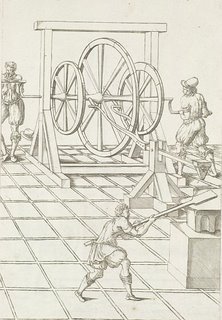

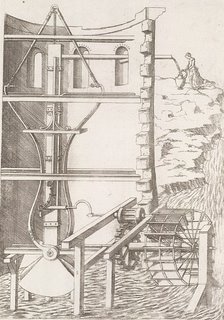

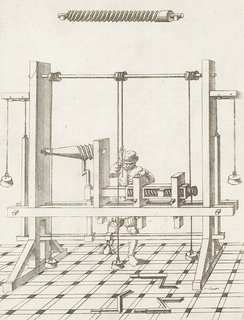

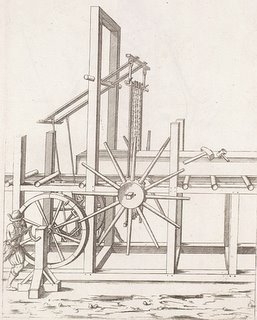

In the 2nd half of the 16th century a genre of technical publications emerged that are collectively known as the 'Theatre of Machines'. These were highly illustrated books which sought to bring both the fanciful and innovative machines to the literate public.

It was the mathematician, engineer, pastor and chemist Jacques Besson's

Theatrum Instrumentorum et Machinarum which gave its name to the body of works that were produced for 2 centuries. A minor edition of this book was first issued in 1573 but the complete treatise, from which the above images have been taken, came out in 1578. There had been other mechanical publications but what set Bresson's book apart is that it was documenting his inventions rather than describing what was already in existence,

per se.

Incidentally, the book's dedication apparently attempts to establish both copyright and patent ownership, under royal patronage - a very early and novel assertion for a renaissance work.

60 copper plate engravings by René Boyvin depict "lathes, stone cutters, saw mills, horse carriages, barrels, dredges, pile drivers, grist mills, hauling machines, cranes, elevators, pumps, salvage machines, nautical propulsion machines, and many others."

“Economic necessity certainly was not the motivating force behind the plethora of technological novelties. They were the products of a fertile imagination that took delight in itself and it its ability to operate within the constraints of the possible, if not the useful. Some of the novel mechanisms pictured in the machine books were later incorporated into practical devices; others stand unused as proof of the fertility of the contriving mind.” (Basalla, 1988)