"Fashionable" hairstyles for women began their vertical climb in the late 1760s, and with them rose the ire of social critics. Editorials appearing in London periodicals immediately decried the large headdresses that English ladies were all too eager to copy from their French counterparts.

Chronicling the rise and fall of the fashion takes us from the courts of France to the printshops of London and finally to the streets of Philadelphia in 1778, where all that the high roll represented in a new nation at war with an old empire was brought quite literally to a head."1

1777 etching published by Matthew Darly. The head of a young woman in profile is the foundation of a monstrous inverted pyramid of hair decorated with vegetables; carrots predominating. On the top are heaped a large bundle of asparagus, a set of scales in one bowl of which are potatoes, a bunch of herbs (taking the place of the ostrich feathers of fashion), a cabbage, turnips, &c. Large carrots take the place of the large curls then worn flanking the coiffure; three bunches of carrots are the main decoration of the surface of the hair, on which are also a cabbage and clusters of leaves (or lettuces). Trails of pea-pods hang from the top of the head-dress after the manner of the lace lappets and ribbons then worn.

Etching published by Matthew Darly in London in 1777. The head of a woman in profile is the foundation of a monstrous inverted pyramid of hair, decorated with the wares of a fruiterer. On the top are a basket of peaches and a large pineapple with its leaves. Down the side of the pyramid, where curls were worn, are large gourds of different shapes. The hair is further ornamented by two tall pottles of strawberries, bunches of grapes, pears growing on branches, a basket of plums, a basket of raspberries, and other fruit.

Published by J Lockington in 1777, this etching shows a lady with her hair in a gigantic pyramid, protected by an enormous umbrella on a very long stick. Her draped over-skirt projects at the back in mountainous folds (support known as the 'corks's rump'). On these is seated a foppishly dressed man taking shelter under the projection of her hair. A simple countryman, whose hat has fallen to the ground, gapes at the pair in amazement. A fashionably dressed man on the right leers and points at them.

A lady in profile with an enormous pyramid of hair in the fashion of the day. On the broad summit of the pyramid lies a miniature cupid fitting an arrow to his bow and about to aim in the direction in which the lady is looking. She wears the fashionable 'full-dress' of the period.

Anonymous etching from about 1775. Satire on coiffures: A Frenchwoman with a ridiculously tall hair arrangement turns in amazement as an Englishman shoots at a flock of birds nesting in it.

{Source. Also see a variation on this theme in colour: includes more images [Pt. 1]}

"The Belle Poule was a French frigate of the Dédaigneuse class, designed and built by Léon-Michel Guignace, famous for her duel with the English frigate HMS Arethusa on 17 June 1778, which began the French involvement in the American War of Independence."

"One of the most fashionable hairstyles of the eighteenth century, À la Belle Poule, commemorated the victory of a French ship over an English ship in 1778. À la Belle Poule featured an enormous pile of curled and powdered hair stretched over a frame affixed to the top of a woman's head. The hair was then decorated with an elegant model of the Belle Poule ship, including sails and flags."

Anonymous 1770s etching (one of a series, all apparently by the same hand). Satire on coiffures: A Frenchwoman is kissed by her elderly husband, while a procession of cupids climb a ladder along her ridiculously tall hair arrangement to deliver letters to her young lover above.

"After Hogarth and before the French Revolution the humour directed at the French in caricatures is gentler. The satire is usually focussed on fashion and hairstyles, the latter being the subject of this print. The fashion for wealthy French women of the 1760s and 1770s was to wear their powdered hair tall, although this lady's coiffure is monstrously exaggerated."

Anonymous 1771 etching from The Oxford Magazine, showing a hairdresser on a ladder with shears trimming the woman's absurdly high coiffure while a man views the action through a telescope.

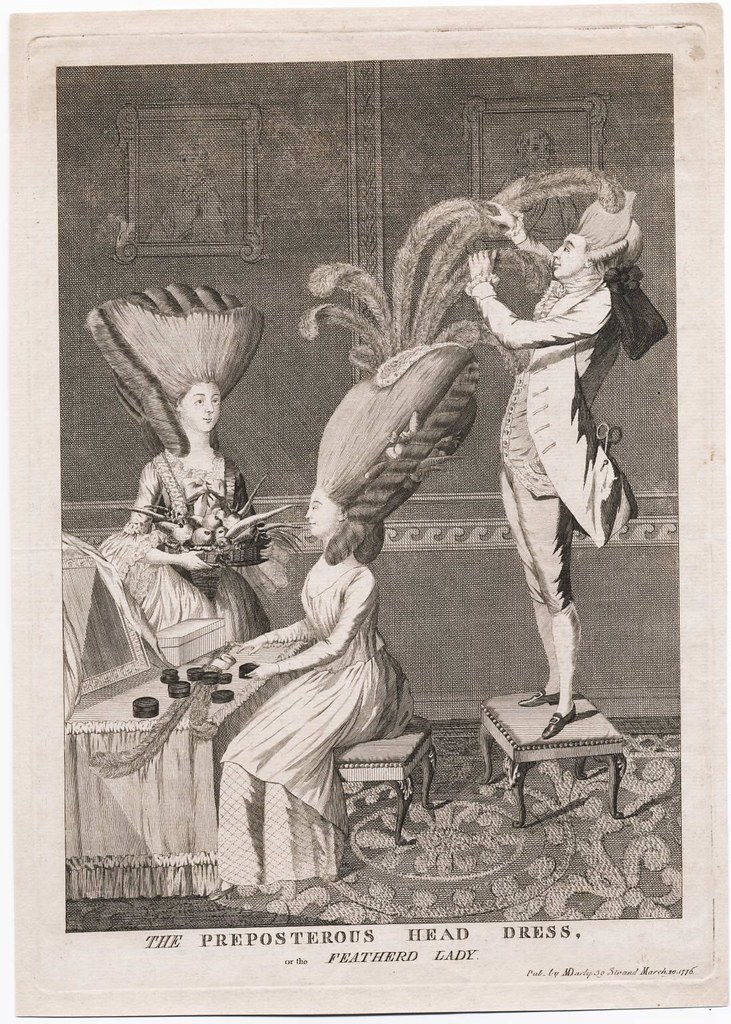

"Both the lady and her maid sport the inverted heart-shaped pyramid all the rage in 1776 and 1777. The Duchess of Devonshire was said to have begun the fashion for ostrich feathers, seen here decorating the headdress along with fruit and carrots. Late in her life Lady Louisa Stuart wrote about the opposition to ostrich feathers as part of a headdress: 'This fashion was not attacked as fantastic or unbecoming or inconvenient or expensive, but as seriously wrong or immoral. The unfortunate feathers were insulted mobbed burned almost pelted.' "

1770s satirical print on coiffures: a Frenchwoman at her toilette wears one huge hair arrangement, while another is being prepared on her dressing table; two maids and a lover attend.

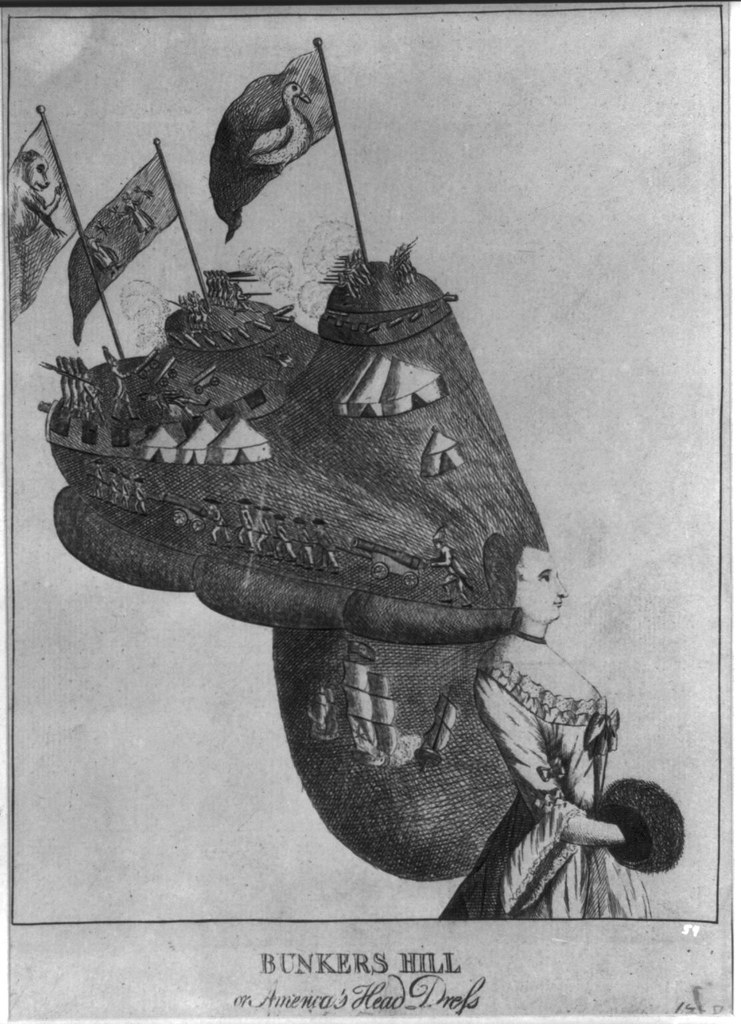

"Prints such as Bunker's Hill, or America's Head Dress, show British troops trudging up the side of a high roll toward their stronghold opposite the American army's 'hill'. The image likened the colonial cause and military effort to the elaborate hairstyle: hollow, artificial, and short-lived."

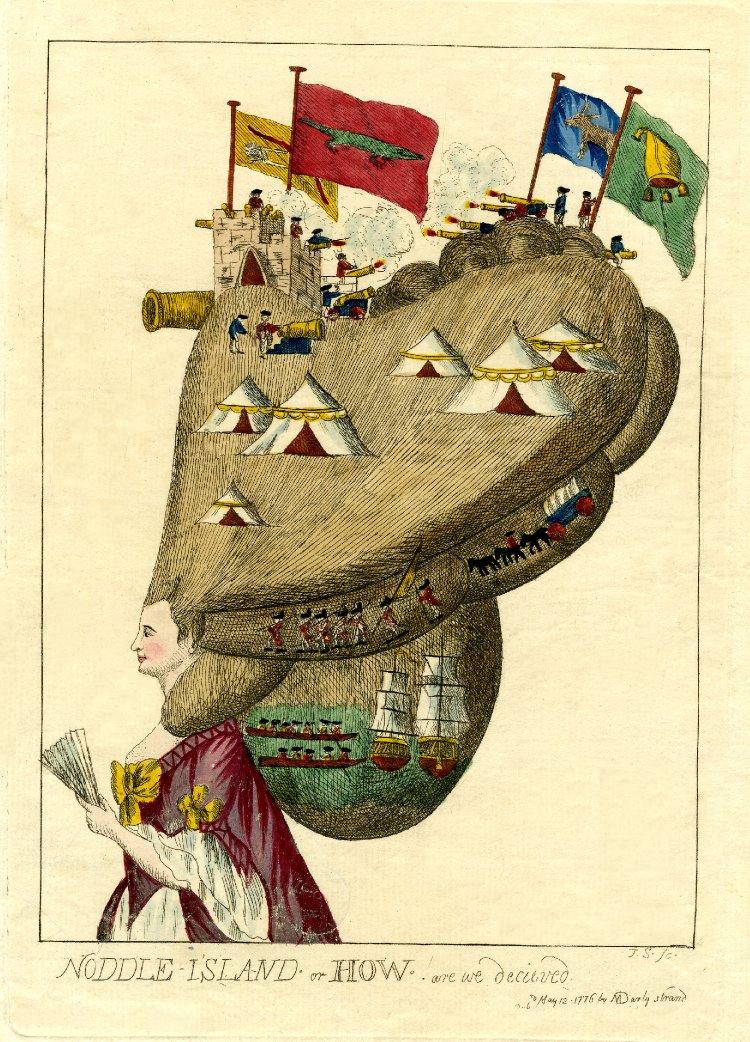

Hand-coloured etching published by Matthew Darly in 1776 depicting a lady on whose grotesquely extended coiffure military operations are proceeding. At the top of her pyramid of hair soldiers fire a cannon from a rectangular American fort at other soldiers firing a cannon from an adjacent mound composed of ringlets of hair. Two immense flags flying from the fort bear, one a crocodile, the other a cross-bow and arrows; the flags of their opponents, the English, are decorated one with an ass, the other with a fool's cap and bells. Below this combat are tents and two men with a cannon. On the lower right rolls of hair red-coats march in single file, followed by a baggage waggon. Lower down again, red-coats in boats are rowing towards two ships in full sail.

This evidently satirizes the evacuation of Boston by Howe on 17 Mar. 1776. There were many protests against the misleading account given in the 'Gazette'. Walpole wrote "nobody was deceived". The 'How' in the title is a pun on the name of the commander-in-chief.

"..an almost hallucinatory invention ... at once barbarous and sophisticated ... The headdress takes on a potency of its own, a literal autonomy of fashion beneath which the wearer is reduced to impersonality." Diana Donald as quoted in this book [Amazon]

"In the upper reaches of this headdress are figures dressed for a masquerade, promenading through a garden. Below is shown what may represent the first regatta in England, held 23 June 1775, partly on the Thames and partly at Ranelagh, where a temple of Neptune had been built. The bearer of this enormous coiffure, despite the female body, may be meant to be Neptune or Father Thames."

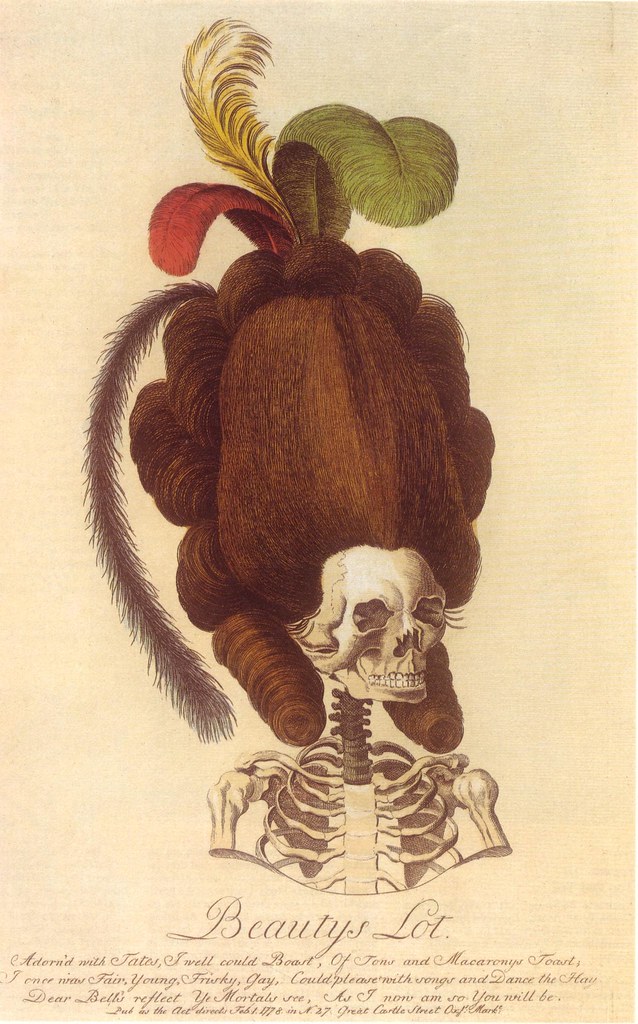

"Shown here is another magnificent heart-shaped pyramid of hair adorned with ostrich feathers, beads, and flowers, of the sort made fashionable by the Duchess of Devonshire in 1776. These hairstyles were labor-intensive and required cushions and wool, pomatum and powder, and an array of decorations. They were uncomfortable, they attracted insects and mice, and they could be fire hazards."

A lady out walking by a lake, dressed in a grotesque caricature of the prevailing fashion. Her petticoats project behind her in an ascending curve, on which lies a King Charles spaniel. Her hair is dressed in a mountainous inverted pyramid, the apex represented by her head; it is flanked by side-curls and surmounted by interlaced ribbons from which hang streamers of ribbon and lace.

Published by M Darly in 1776. The print alludes to the region that is now Ohio which was then part of New France. Unlike the thirteen colonies on the eastern seaboard, New France was never effectively colonized and the population remained small. Since the main interest of the French was commercial exploitation (the basis of the economy was the fur trade), communities remained only frontier outposts.

"The lady and her hair dwarf the horses pulling her carriage, a phaeton. The Duchess of Devonshire may be the intended object of the satire here, given the ostrich feathers in the hair and the ducal coronet on the carriage."

Juxtaposition of sedan chairs, one modified to accommodate the ridiculously exaggerated coiffure of its female occupant.

1827 print by William Heath and published by Thomas McLean. Dancing couples (including a man in Hassar uniform) with absurd hairstyles.

Etching published by M Darly in 1771 with a young woman dancing to the violin played by her dancing master, while her proud mother sporting an enormous hairdo looks on. (note the poodle and monkey. The monkey, particularly, is a recurring satirical motif in many of these prints: preening? 'aping'? no smarter than apes?)

Anonymous 1776 etching of a young woman with her hair in a much exaggerated inverted pyramid which fills the greater part of the design and is the support for a dressing-table, draped with muslin festoons. On it are an oval mirror, a pair of tapers in candlesticks, two vases of flowers, a pin-cushion, toilet articles, a pair of buckles, rings, a necklace, &c, two books, a pen.

"Embellished with the French Favourite Circle called a la Zodiaque just imported. see Lady's Magazine N. XC. Humbly dedicated to the fine Ladies of the petty gentry by Monsieur Periwig from Paris." {Engravings by Miss Heel in 1777}

Published by M Darly in 1777

Two extravagantly dressed women face each other, each seated on, or rather supported by, an enormous cork which projects from the neck of a bottle. Both are elderly, one (left) enormously fat, the other very thin. Both wear the grotesque pyramids of hair, flanked by ringlets like large sausages and surmounted by ostrich-feathers, so much caricatured since 1776. Their skirts are skimpy in front, showing the contour of their legs, but project in great panniers at the back. Both are gloved and hold fans. The cork and bottle of the fat woman is correspondingly broader than that of her thin vis-à-vis.

Published in 1777 by J Lockington, this half-man half-woman print contrasts the gender styles of the time, exaggerating the female fashion and hairdo, while the male's appearance is more natural by comparison.

Hand-coloured mezzotint published by Carington Bowles in 1771. The counsellor and his client sit facing one another across a table, beneath which their knees touch. The lady wears a grotesquely high pyramid of hair, decorated with pearls or beads and a high lace cap with ribbons and lace lappets. She looks intently at the Counsellor who is wearing a legal tie-wig, gown, and bands. On the wall is a framed picture of two monkeys sitting on each side of a round table, each with a tea-cup.

Hand-coloured print by James Gillray, published by Hannah Humphrey in 1795: a satirical response to the tax on hair powder; including a portrait of Charles II with a huge powdered wig.

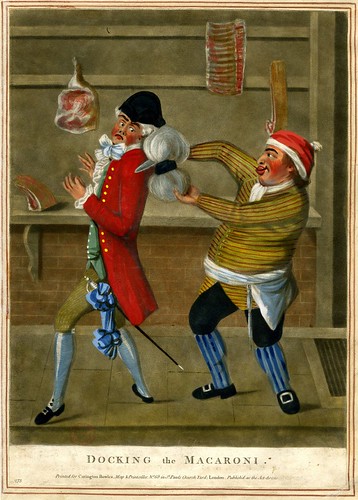

1773 hand-coloured mezzotint published by Carington Bowles of a butcher in front of his shop slicing off the ponytail of a passing Macaroni.

Mezzotint by Philip Dawe; printed for John Bowles in 1773

"This gentleman shows off the fashion of the day, from the rosettes on his shoes to the tiny three-cornered hat at the top of his headdress, a structure made of enormous side curls, a gigantic club, and a pyramid of hair. While the Oxford English Dictionary cites Walpole’s comment in 1764 as the first recorded use of the term, the Macaronies came to greatest prominence in the early 1770s."

Many of the above images have been spot/background-cleaned. The commentary is quoted or paraphrased from source sites (and elsewhere), as linked below.

The images were obtained from the following sites (in order of contribution numbers):

- The British Museum Collections Database.

- The Walpole Library Digital Collection at Yale University (via the exhibition site listed below).

- Vive la différence! The English and French stereotype in satirical prints, 1720-1815 at the Fitzwilliam Museum.

- The Library of Congress - Pictorial Americana.

- The Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection at Brown University.

- Thanks very much, yet again, to Will from AJRMS for sending a couple of scans my way which inspired this post {also see his bookplate contest and the 'best of'/overview post}

- Preposterous Headdresses and Feathered Ladies: Hair, Wigs, Barbers, and Hairdressers -- a Lewis Walpole Library exhibition.

- 1A Short History of the High Roll by Kate Haulman (2001) at Common-Place.

- Big Hair: A Wig History of Consumption in Eighteenth-Century France by Michael Kwass (2006) IN: The American Historical Review.

- Mary and Matthew Darly.

- 1750-1795 in fashion.

- UPDATE: I forgot about this catalogue [pdf] from Cora Ginsburg that has a page overview and a couple of images - among some other interesting things - from a contemporary book devoted to the art of the coiffure: 'L'Art de la Coeffure des Dames Françoises, avec des Estampes, ou sont Représentées les Têtes Coeffées' by Legros de Rumigny, 1768-1770.

- UPDATE 2: There are a few more "hair" pictures in the old post, Easy Pickings.