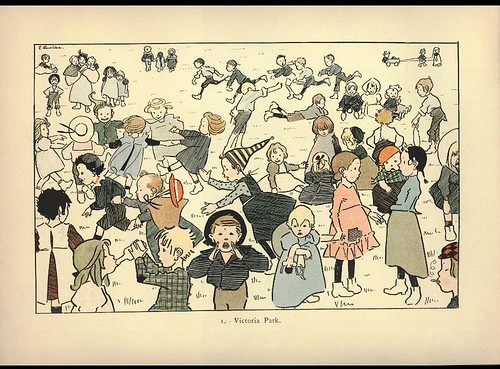

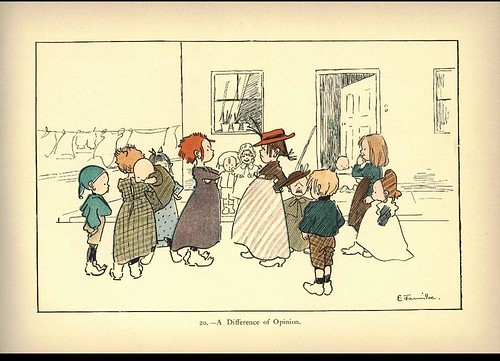

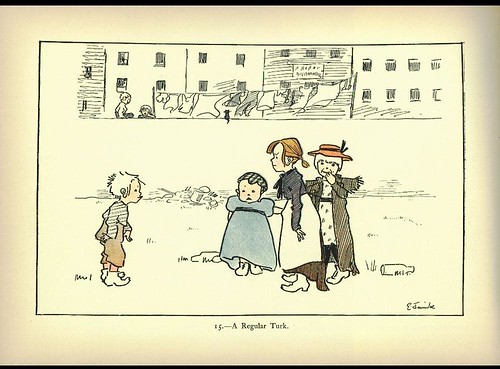

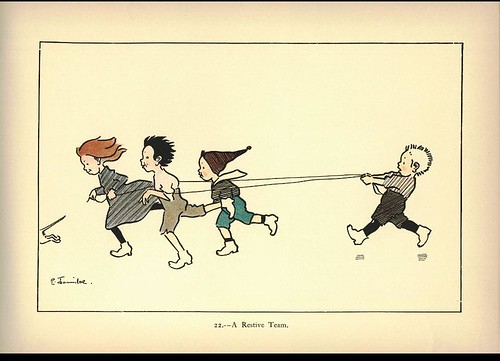

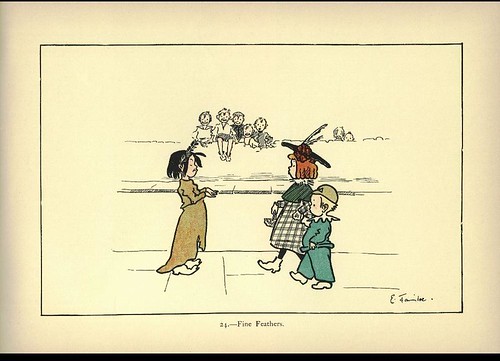

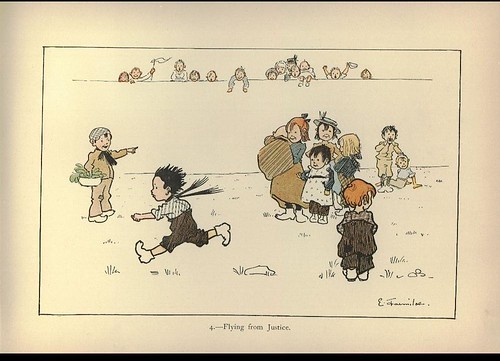

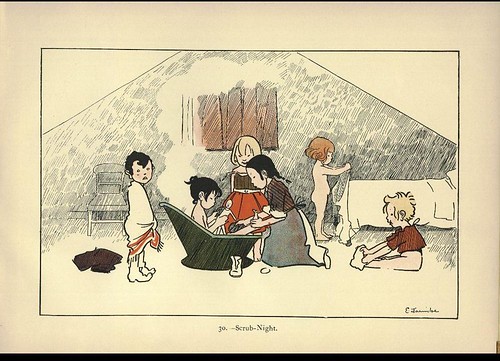

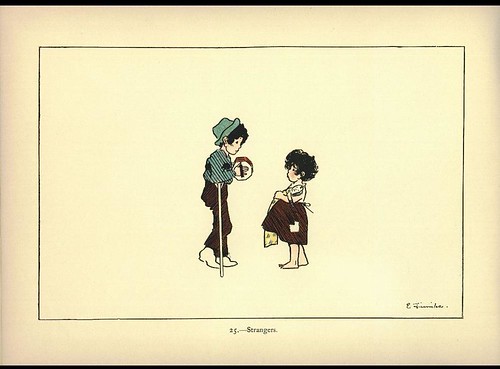

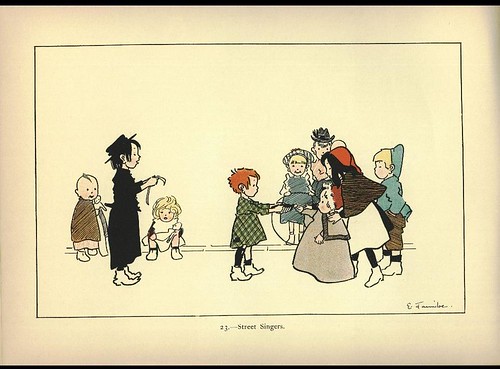

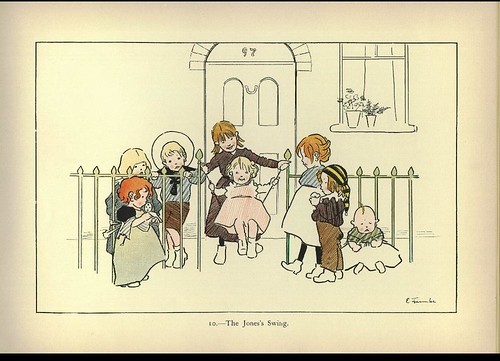

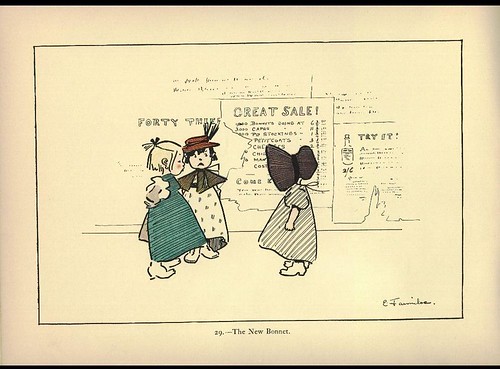

These charming chromolithographs of children from 1899 by Edith Farmiloe appear in a book called 'Rag, Tag and Bobtail', available from Braunschweig Digital Library (click 'Start.html') I confess to not having read any of the verses by Winifred Parnell in this ~70 page book : temporary bandwidth problem. The images above have all been lightly background cleaned.

There is little online about Farmiloe*, although the paragraphs below (out of sequence) from a contemporary review by Walter Shaw Sparrow in an arts magazine called 'The Studio', are alone worth reading for the authors delicate interplay of patronising attitude (well it was 1899!), attempted deference and subdued incredulity at the wily ways of feminine illustration ability.

*Known but unavailable from Amazon; appears in a few ebay auctions; otherwise pops up in a few antiquarian bookstore listings.

'The Studio' is one of a couple of old art magazines available from Design Research Publications. The excerpted article below - 'Some Drawings by Mrs Farmiloe' : Walter Shaw Sparrow - is from Issue 81: December 1899.

In passing, I came across this work that seems pretty good: 'The Victorian Illustrated Book' Ed. by Richard Maxwell, 2002. [googlebooks]

"Mrs. Farmiloe is the second daughter of Colonel the Hon. Arthur Parnell, a retired officer of the Royal Engineers and a second cousin of the late Irish leader, Charles Stewart Parnell. She has four sisters and four brothers, and a talent for humorous drawing runs in the family. Her husband, the Rev. William D. Farmiloe, is Vicar of St. Peter's in Soho. The parish, lying chiefly between Rupert Street and Great Windmill Street, is thronged with children of all nationalities, and Mrs. Farmiloe never tires of watching the youngsters play when school is over, Something of what may be seen there is admirably represented in the artist's new book, "Tag, Rag, and Bobtail" (London: Grant Richards). Herein the drawings are reproduced in colour, and one finds everywhere plenty of sweet ingenuousness with plenty of gay and charming movement and humour. It is a book to be treasured, like its predecessors of last year–a work entitled "All the World Over." [..]

One other point is worth noting in connection with the difficulty that Mrs. Farmiloe experiences in handling details. She tells me that she cannot sketch well from nature, as she is bewildered by the great number of lines which have to be drawn one by one; but when she turns away from the object and sets herself clearly to visualise it, to see it clearly with her mind's eye, the feeling of bewilderment leaves her, and the model's chief lines are soon upon paper. This skill in drawing from memory is often very helpful to Mrs. Farmiloe, for children never know when they are being " took," and consequently never pose and look unnatural. She can take part in their amusements and yet be their graphic historian. On the other hand, it is also a dangerous way of working, since it is apt to give rise to stereotyped conventions, to endless repetitions, so that this tendency ought to be counteracted by patient studies from the life, The drawings thus made may be bad, yet they store the mind with new and varied material, which is certain to find its way into the next memory-sketches.

And I say this because a few children in Mrs. Farmiloe's art have a family likeness, a set type of face and figure. We must remember, nevertheless, that in writing about a lady of genius a man may easily give bad advice. "Women," said Goethe; "do the most through imagination and temperament." Their best work has ever been done intuitively, under an instinctive rather than technical guidance. They have eyes to see and hearts to understand a great many subtle things unperceived by men; hence we are often seriously at fault when we try to influence their ways of working. This is what Mr. Ruskin found out in the case of Lady Waterford, the greatest woman-artist of the century, who was rendered timidly self-conscious by a course of systematic instruction. Nature was her best guide, as Mr. Ruskin soon acknowledged.

In brief, academic studies do much for men, but it is doubtful if they are ever very useful to women of first-rate ability; and thus I may be altogether wrong in my remarks on the benefits that Mrs. Farmiloe would receive from studying from the life. This is a point which she alone can decide, guided by her intuitions."