"They were incredibly small, nay so small, in my sight,

that I judged that even if 100 of these very wee animals

lay stretched out one against another, they could

not reach to the length of a grain of coarse Sand."

[Antonie van Leeuwenhoek describes his discovery of bacteria]

Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek's simplistic single-lens microscope from the ~1670s in which two screws allowed the distance from the lens and the up-and-down movement of the specimen to be adjusted.

[source]

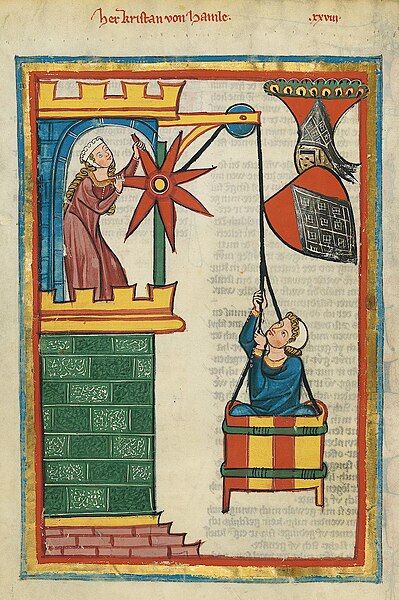

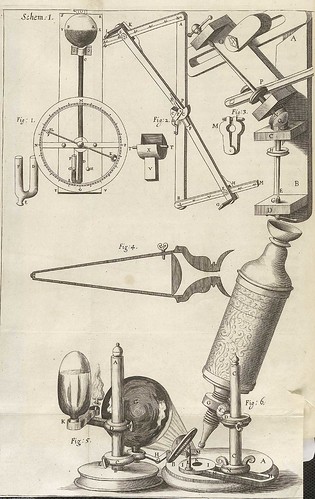

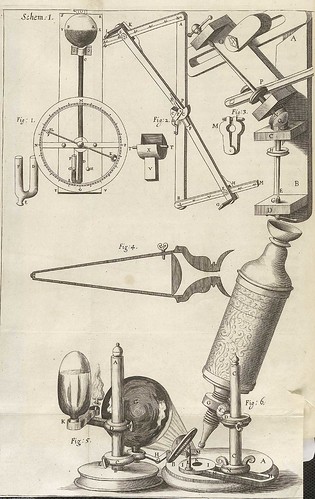

Johann Franz Griendel published the first German book on microscopy in 1687.

'Micrographia Nova' was obviously greatly influenced by Hooke's classic work but it wasn't mere homage. Griendel documented significant advances in the objective lens and depth of visual field from instruments he had manufactured himself.

'Micrographia Nova' is available complete, in two sections, from the Universities of Strasbourg - Digital Old Books (SICD)

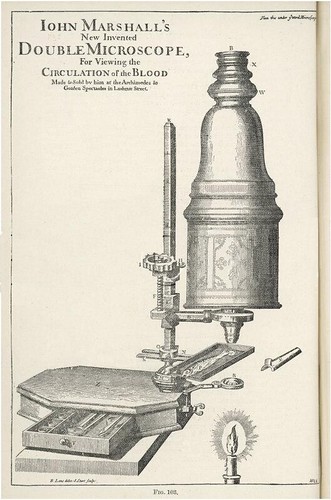

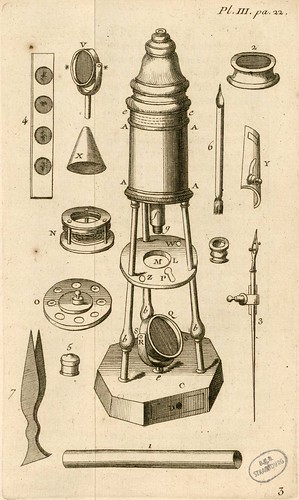

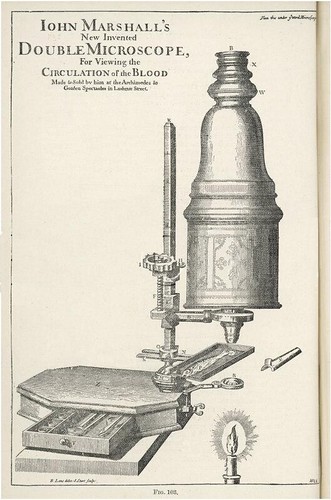

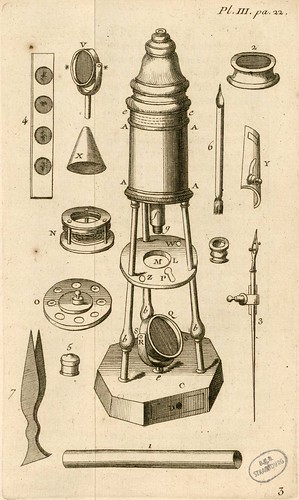

John Marshall's New Invented Double Microscope

for Viewing the Circulation of the Blood (~1698-1700)

"

Marshall called his microscope the Great Double microscope for two reasons: he wanted to illustrate the large size of the microscope and to reinforce the fact that it was a compound microscope." [..] "One of the most significant features of Marshall's microscope was the fine focus mechanism, which was a very unique design element for the period. The mechanism functioned through a series of sleeves that attached the microscope body to the limb. One sleeve served to attach and adjust the position of the body tube to the limb, while the other moved the body tube up and down with a small focusing knob."

[By the time I removed the enormous and intrusive watermark from this image, I had *somehow* forgotten the name of the commercial art site from which it was sourced.]

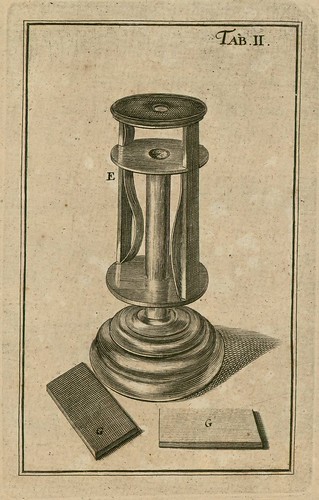

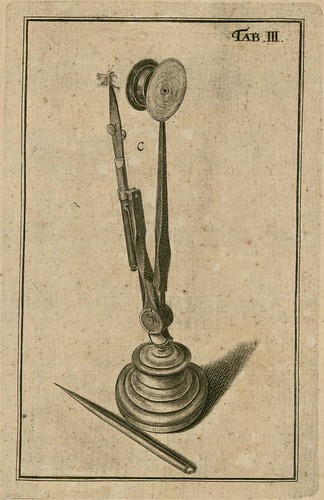

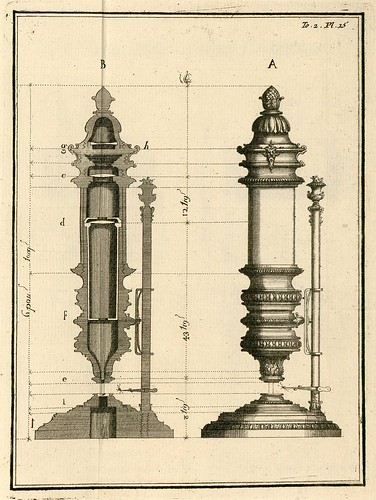

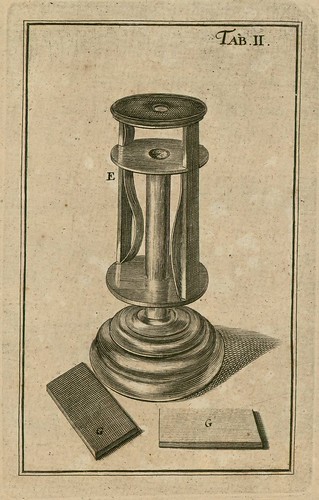

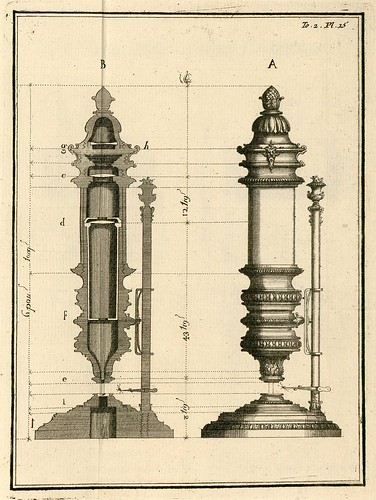

The above images come from

'Kurzer Unterricht von der Beschaffenheit und dem Gebrauch der Vergrösserungsgläser und Teleskopien' (~Short lessons of the Constitution and the use of magnifying glasses and telescope) 1747, by

Joachim Friedrich Meyen, online at SICD.

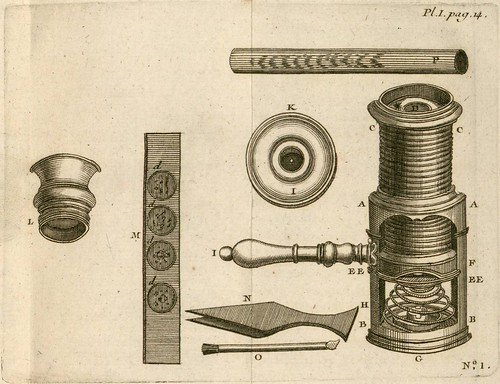

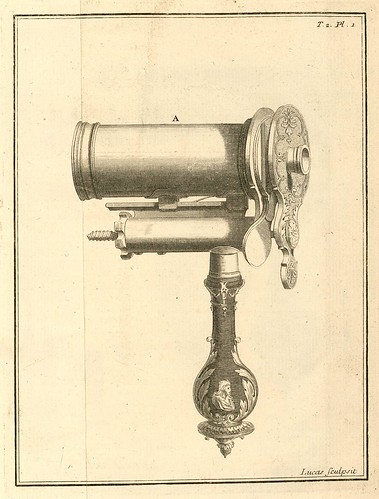

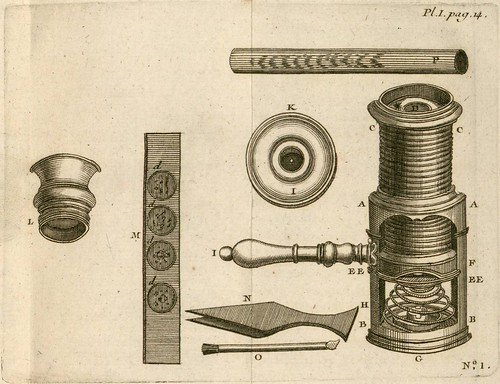

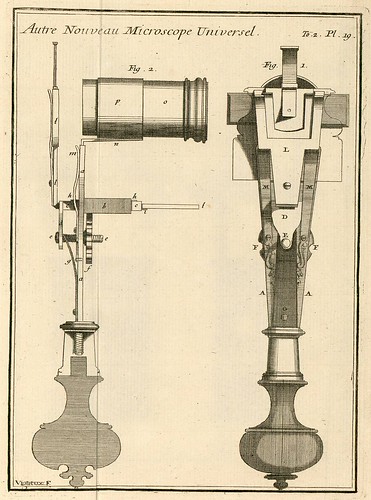

From:

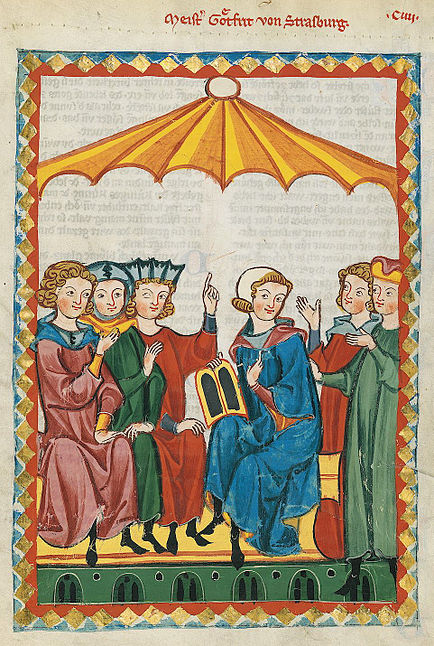

'Le Microscope à la Portée de Tout le Monde', the French translation of Henry Baker's 1742 publication,

'The Microscope Made Easy', available from SICD. [Googlebooks have a microfilm copy of

the original]

"

Simultaneously a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and the Royal Society, Baker was a naturalist whose microscopical observations of aquatic animals and fossils were of interest to a wide audience. In 1744, his study of crystal morphology garnered Baker the Copley Gold Medal for his microscopical work and inspired other scientists to engage in systematic microscopic studies of crystalline formations. Many of the materials he examined were observed through a compound microscope made by the English optics expert John Cuff (1708-1772), which he designed at Baker's behest."

"The works of nature are the only source of true knowledge, and the study of them the most noble employment of the mind of man.... Microscopes furnish us as it were with a new sense, unfolding the amazing operations of nature, and presenting us with wonders unthought of by former ages."

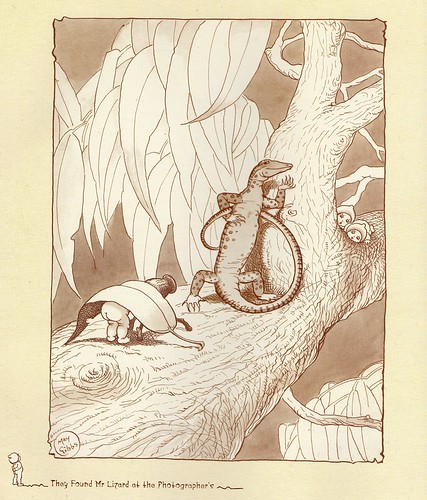

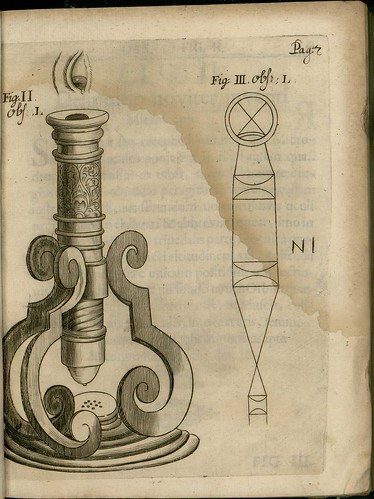

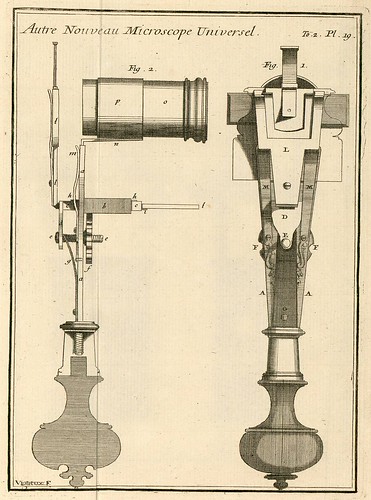

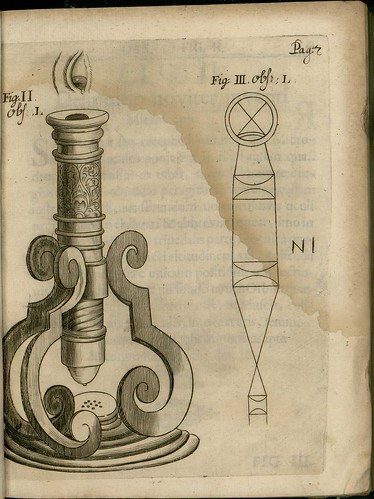

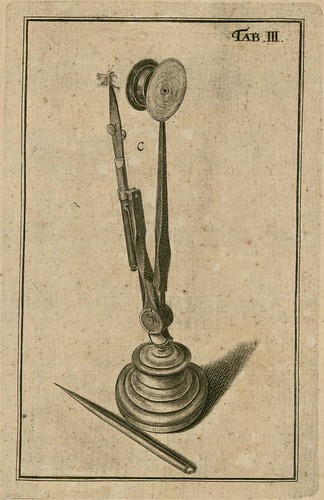

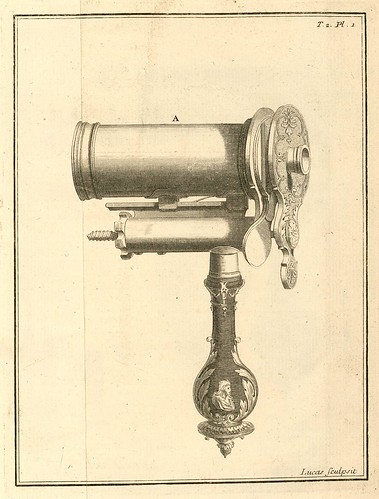

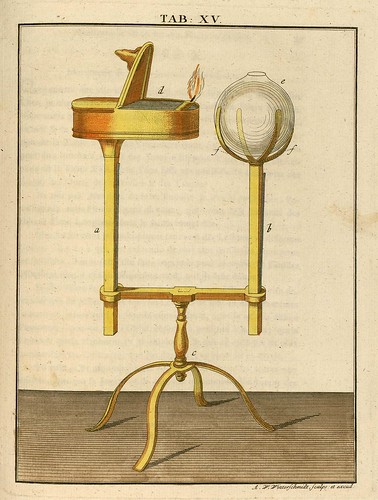

The above illustrations come from

'Observations d'Histoire Naturelle Faites avec le Microscope', 1754/55, available in 2 parts at SICD.

"

Louis Joblot (1645-1723), a professor of mathematics at the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Paris, combined his interest in science and art through the use of a microscope. Beginning in 1716, he devoted most of his career to exposing the wonders of the microscopic world. Although not published until 1754, the illustrations and text for his Observations on Natural History Made with the Microscope were completed thirty-six years earlier."

"Joblot's instruments represented an advancement over those available before him because of the quality of the mechanisms permitting precise focusing, the excellent design of his tubular diaphragms, which eliminated stray light, and the multitude of his well-planned attachments for mounting the most diverse types of specimens." [pdf in-browser:

'Louis Joblot and his Microscopes' by Hubert Lechevalier, 1976 IN:

Bacteriological Reviews {

alternative link} -- well worth reading if you are

into microscope/microbiology history]

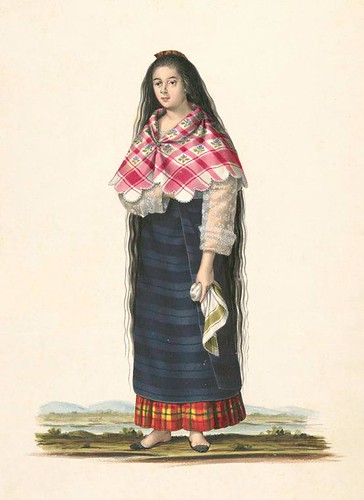

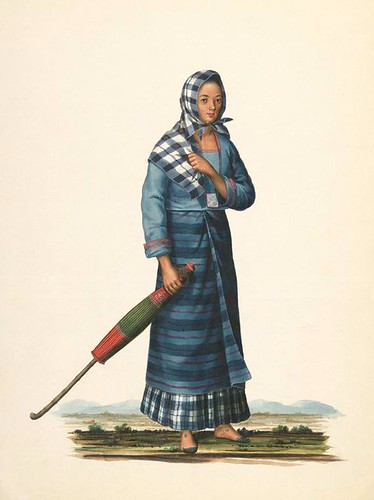

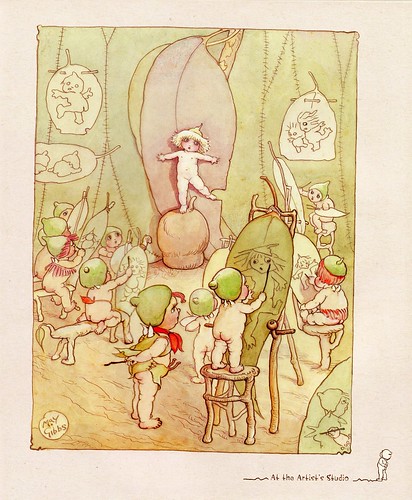

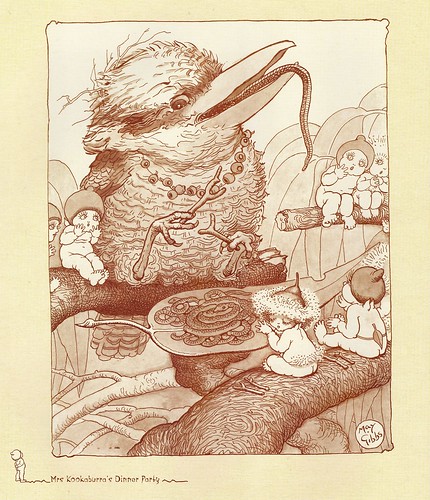

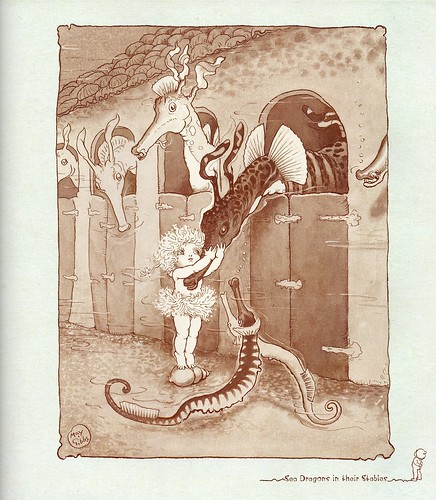

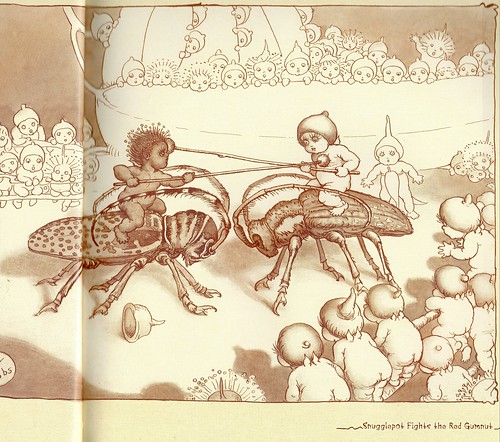

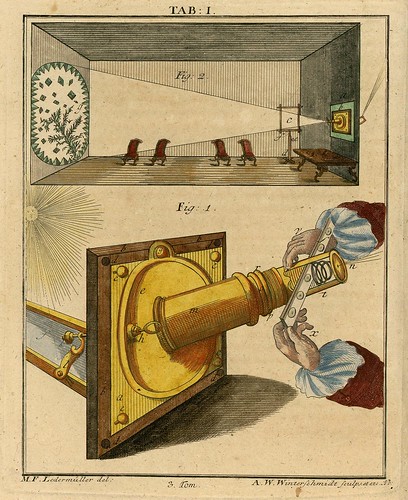

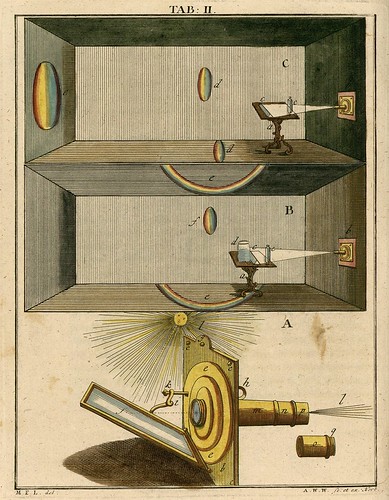

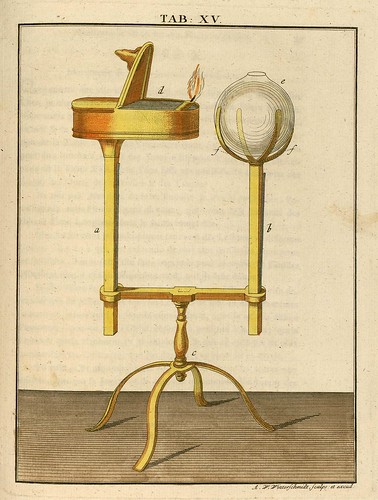

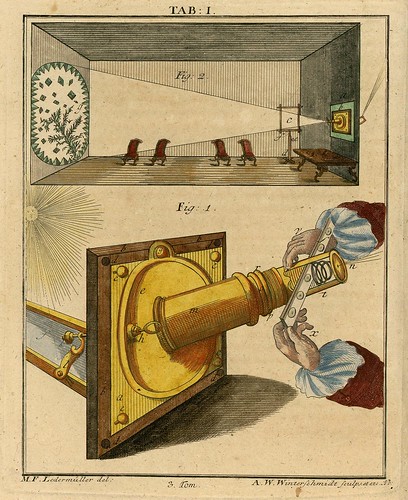

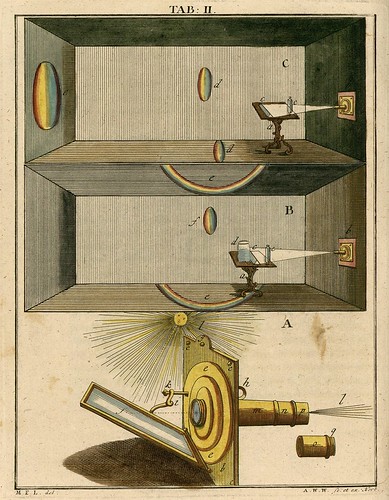

All the above colour illustrations come from the Martin Frobenius Ledermüller series from the 1760s,

'Phisicalisch Mikroskopische', online at SICD.

The previous Ledermüller post is definitely worth seeing for the spectacular drawings of microscopic specimens and includes some biographical details. Ledermüller seems to have taken a cue from the reception given to Hooke's work from the previous century and added elements of theatricality and embellishment with the honourable intent of making the microscopic world popular and entertaining.

-------------------------

The path to the development of the microscope really began* in 11th century Iraq. The empirical scientist and polymath,

Ibn al-Haytham (

Alhazen), produced a massive treatise called

'The Book of Optics' in which he recorded experimental data and theories pertaining to lenses, binocular vision, mirrors and the observable properties of light. It is without doubt one of the most influential books ever written.

'The Book of Optics' outlined the rationale for practical scientific methodology that continues to resonate through every scientific discipline today. Translations of Alhazen's work circulated widely in Europe and his writings were a primary guiding source for all the major innovators in microscopy, astronomy and optical physics during the 16th to 18th centuries.

[*There's an intentional omission of references here to any ancient Egyptian, Greek and Roman observations about crystals, glass manufacturing and magnification phenomena because they don't appear to have had a direct role in the evolution of technologies that culminated in the invention of the microscope.]Roger Bacon gave an account of the properties of biconvex lenses and their use in magnification in the 13th century. There are also ambiguous references in his work to an instrument with telescope properties. It is probably not incorrect to attribute the invention of the magnifying glass to Bacon, but as his written legacy lacks formal instrument descriptions, it is difficult to give him further credit, save for footnote status, in reference to microscope/telescope development. There is some splitting of hairs with such a conclusion. The evaluation necessitates a drift into semantics; a microscope might be said to differ from a magnifying glass (although the former, in a simple system, is an example of the latter) in that it has an applied scientific dimension -- for use in examining cells or plants etc, smaller than can be resolved by the unaided eye, for the purpose of acquiring knowledge -- rather than being a generic instrument capable of making small things appear larger. So Bacon is important in the timeline of optical physics, but slightly less so in the specific path to the production of the task-specific instrument called a microscope. This is of course open to debate. Coincidentally (or maybe not), the 13th century saw the first lenses produced as vision correction devices.

It's a fairly safe bet to assume that the quality of glass and lens production improved over the following two centuries both as a result of the heightened exchange of information during the Renaissance and because the prevalence of eyeglass makers was on the rise. Conditions, therefore, became favourable for innovation. And although the story remains somewhat murky, the balance of opinion has it that towards the end of the 16th century, the telescope was invented by Hans Lippershey and, soon afterwards, the compound microscope (an instrument with a system of two or more lenses in series) was invented - in about 1595 - by Zacharias Janssen, undoubtedly with the help of his father, Hans Janssen. Lippershey and the Janssens were all eyeglass makers and they all lived and worked in the town of Middelburg in Holland. I have no idea whether they were acquainted but what are the chances? [Attribution to Lippershey/Janssens is not universal; some sources appear to regard Lippershey as the inventor of both and others see Galileo's contributions as warranting the title of inventor. It may well be that more than one person created a functional instrument at about the same time, independently.]

Irrespective of the exact circumstances that gave rise to the invention of the microscope, the device itself or the instructions for building a microscope had arrived in Rome during the first decade of the 17th century. Galileo included both a concave and a convex lens in the compound microscope that he built, which he called

occhiolino (little eye). In the early 1620s, this instrument was being used by fellow members of the venerable scientific society, the

Lynx Academy. One of the Academy members, Giovanni Faber, renamed the device

'microscope'; and by the end of the decade, Francesco Stelluti (also a member), had published the first illustrations of objects - [bees:

previously] - as observed under a microscope.

The first scientific paper that relied upon the findings from microscopic studies was published in 1661. The Italian physiologist, Marcello Malpighi

[previously], may not be a household name, but he was the first serious microscopist and made invaluable contributions to our understanding of microanatomy. In that original paper, Malpighi recorded his observations of blood circulation in the connecting vessels - the capillaries - between arteries and veins in frog lungs which provided the vital piece of supporting evidence for the theory of the circulation of blood, postulated by William Harvey in the year of Malpighi's birth.

In 1665,

Robert Hooke published

'Micrographia' [previously] to great acclaim. This lavish work introduced the science fiction-like microscopic world of familiar items - the head of a pin, the structure of a flea etc. - to a mesmerised public. It was the sensation of the age. With its sixty highly detailed plates and articulate, yet accessible essays,

'Micrographia' simultaneously motivated the world of academia to pursue experimental science with gusto and the lay intelligentsia to obtain their own instruments so they might experience similarly amazing sights as a leisure activity.

The final character of note from the early years of microscope development was almost certainly influenced by Hooke's masterpiece.

Antonie van

Leeuwenhoek [books] visited England in the late 1660s and thereafter devoted his life to the pursuit of lens and microscope construction. Although he published no scientific papers, Van Leeuwenhoek was a regular correspondent with the Royal Society, who granted him membership in 1680. He was renowned as an expert in producing lenses of great clarity and resolving power (to one micron), despite the majority of his microscope designs being of the single-lensed magnifying glass variety. The incredible number of lenses made during his life points to the likelihood that Van Leeuwenhoek had perfected blown glass techniques for their creation rather than continuing with the time intensive grinding process followed by the majority of his peers. But he was always secretive about his working habits and took his lens making and illumination practices to his grave. Van Leeuwenhoek is credited with the discovery of bacteria, protozoa, spermatozoa, rotifers, hydra and volvox.

[As per usual, the choice of illustrations above was largely determined by what was available/what I found and shouldn't be taken as a 'definitive illustrated guide to the history of microscopy' or the somesuch. The same goes for the text: all care is taken (hopefully) but what I've written shouldn't be regarded as authoritative. There may be intentional mistakes. Or there may not. The history is convoluted and complex and requires reading from a number of sources. In fact, I'm not sure the internet is the best place to do this.]- I was prompted to finally get this entry together, having squirrelled away links for ages, by the announcement from Oxford University that the (beta) Collections Database from the History of Science Museum had now gone live (hint: advanced search lets you pick entries with images). Very much related is their 'Small Worlds - The Art of the Invisible web' exhibition site. [Thanks Liz!]

- The Florida State University site, Molecular Expressions - Exploring the World of Optics and Microscopy could keep anyone occupied for

hours weeks. Of particular interest is the Timeline in Optics section with links to a wealth of commentary and biographical essays about the key players. - ars machina have a fairly extensive gallery of microscope photographs, with descriptive commentary.

- Wikipedia: microscope; optical microscope; timeline of microscope technology.

- Timo Mappes also has a fairly extensive photograph gallery of antique microscopes (commentary in German) [homepage].

- 'The sharp-eyed lynx, outfoxed by nature - Galileo and friends taught us that there is more to observing than meets the eye' by Stephen J Gould, 1998 IN: Natural History [single page link].

- 'The Eye of the Lynx: Galileo, His Friends, and the Beginnings of Modern Natural History' by David Freeburg, 2002.

- To be honest, I could add many more links because there is a LOT out there. But unless you have a particular interest - in which case a decent library would be the destination of choice - the above material more than sufficiently covers the subject in my view.

- Update: NLM have an exhibition site: Hooke's Books: Books that influenced or were influenced by Robert Hooke's 'Micrographia' which has had a new section added this month (as part of the turn-the-pages site linked near the top of this entry).