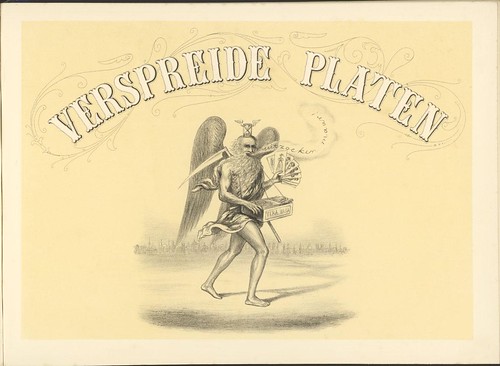

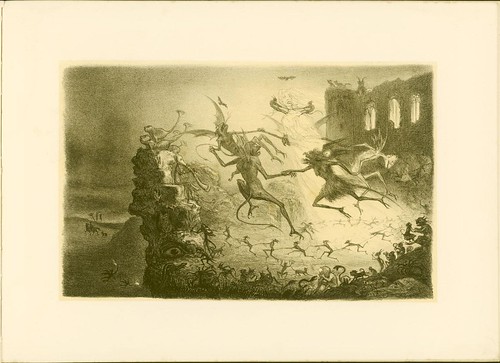

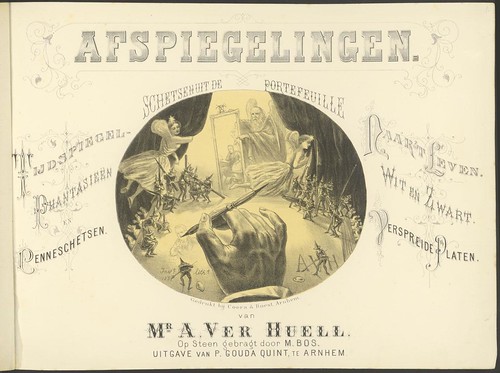

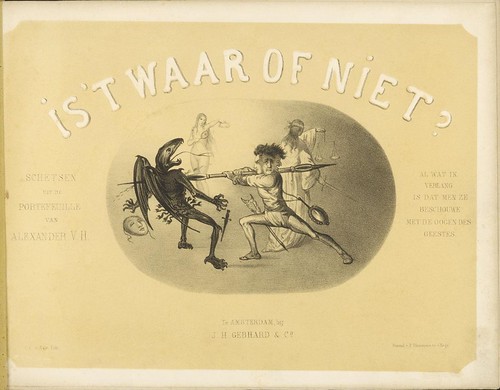

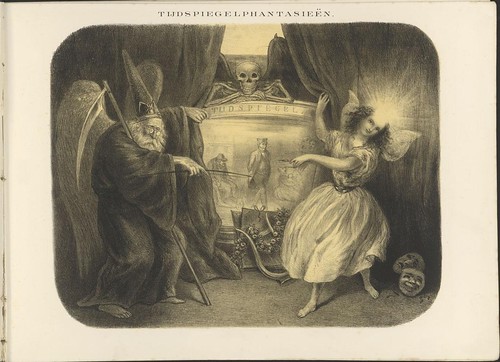

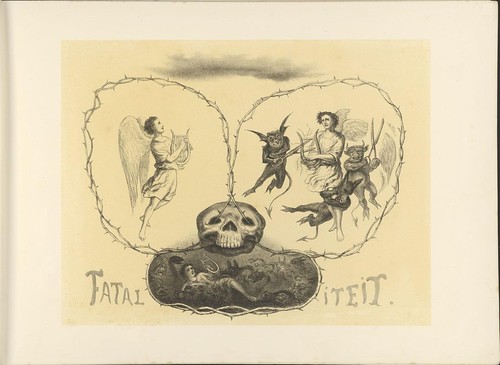

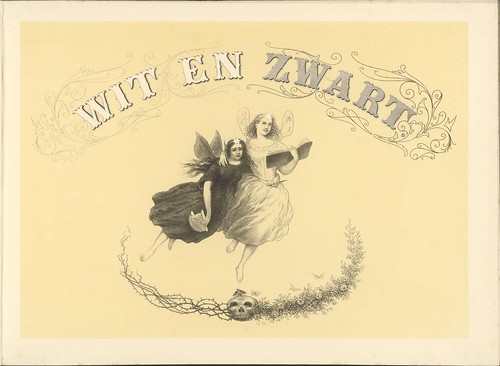

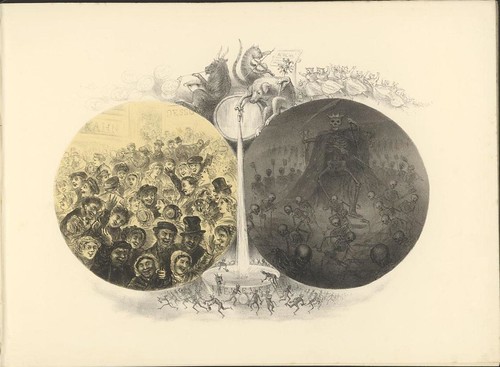

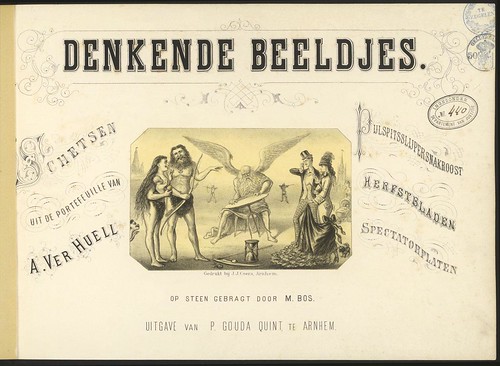

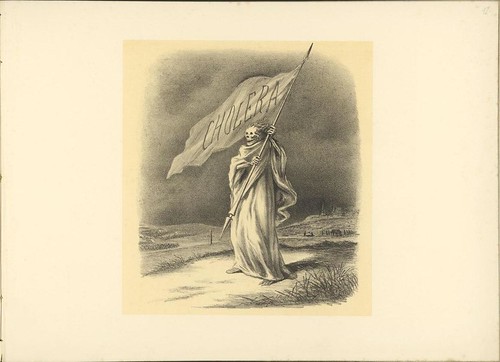

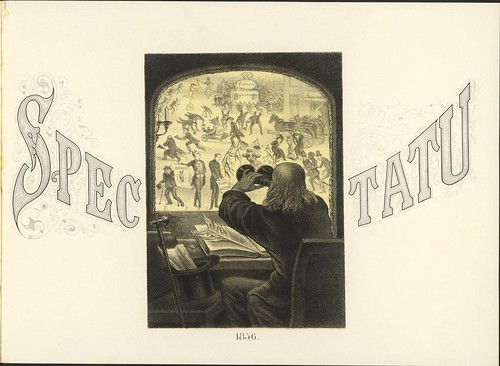

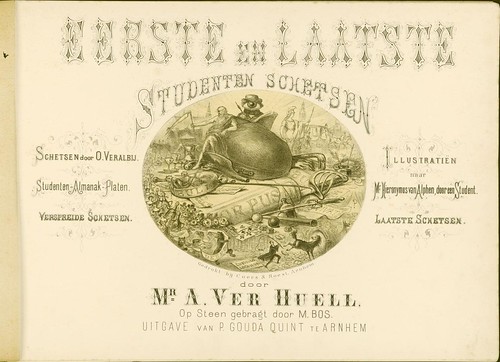

Take one part gorgeous ornamental typography and one part diabolical imagery. Combine slowly over a low heat with incidental visual curiosities. Add caprice to taste. Serve haphazardly over a bed of 19th century lithographic stones. For best effect, consume before retiring.

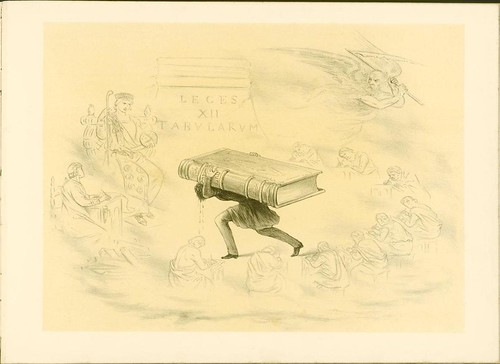

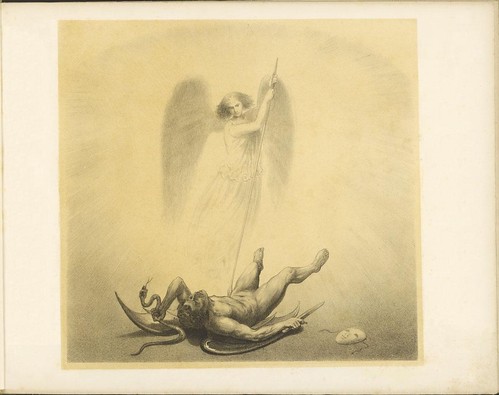

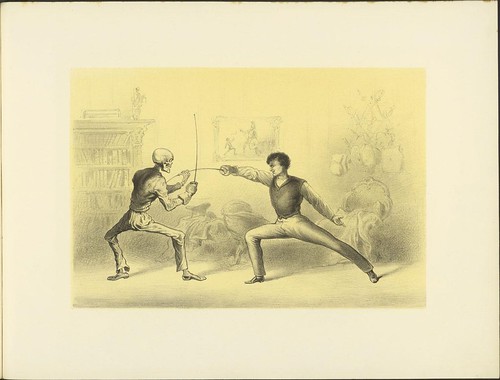

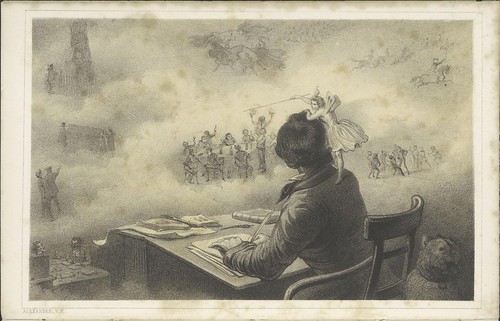

I'm not certain that Leiden graphic artist, Alexander Ver Huell (1822-1897), would agree that this recipe or the meal served above is a fair representation of his life's illustrative output. And he would be right. I've arbitrarily selected works that edge towards the macabre and fanciful rather than the majority of his sketches, which are far more benign, contemporary and humorous. They're definitely not bad at all; just less interesting. That's my caprice.

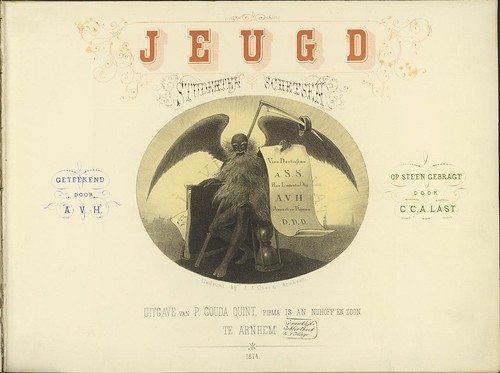

Ver Huell had been a law student at Leiden University which became the focus for a lot of his drawing, even after he completed his degree and subsequent doctorate. Humorous designs for University publications were the foundation of his career and led to book and magazine illustrating assignments. By 1850 he was a well known and respected artist.

As he grew older, however, Ver Huell experienced a change in his personality in which he became more paranoid and socially alienated and his sketches veered away from the whimsical to concentrate on depicting evil and devils. He believed that "an artist has a social function: to fight against Evil" and that "[t]rue artists were misunderstood and persecuted".

Despite his evolving psychiatric problems, Ver Huell maintained close associations with the artistic community both in Holland (where he also tutored art students) and in France, which he visited often. He could count the famous French book illustrator, Gustave Doré, among his long term friends and correspondents.

Ver Huell craved wider recognition for his talents - such strong desire was probably associated with his illness - but even when plans had been made to honour his art late in his life, he rejected the offer because it didn't involve any Royal award or distinction. Ver Huell's mental condition was always on the decline and he died alone after severing ties with friends and publishing contacts. It sounds like the poor bloke had a fairly tortured life.

The Leiden Archives (via the Memory of The Netherlands) have a portfolio of thirty albums/books containing lithographs designed by Alexander Ver Huell on display. Some of them are only microfilm scans with photocopy quality but these are in the minority. There must be several hundred illustrations - sometimes repeated - through the available publications. To download large versions of the images I had to manipulate the URLs - I'm guessing this is a firefox problem because there are download buttons around. A zoom interface is also available.

All of the above images have been spot/stain cleaned to one extent or another.

Some biographical material (short pages) from the Memory of the Netherlands:

¤¤1822-1845 early recognized talent

¤¤The nineteenth-century student

¤¤1846-1879 public success for the tormented artist

¤¤Ver Huell in his time

¤¤Ver Huell in Leiden

Monday, July 28, 2008

Collectie Ver Huell

Sunday, July 27, 2008

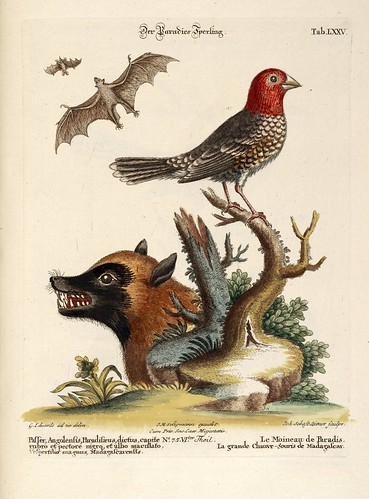

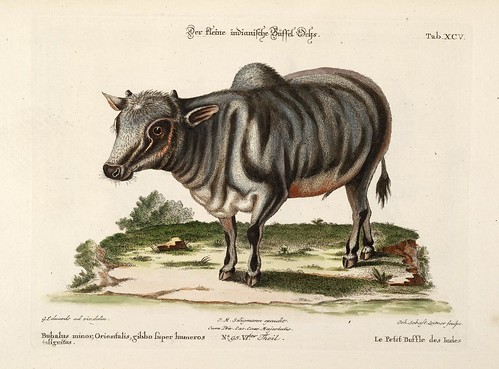

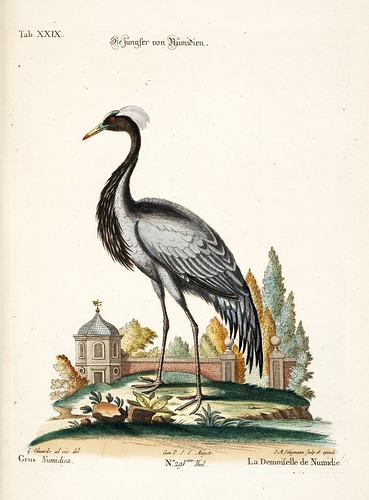

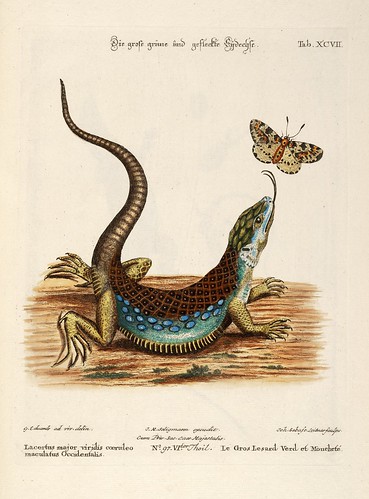

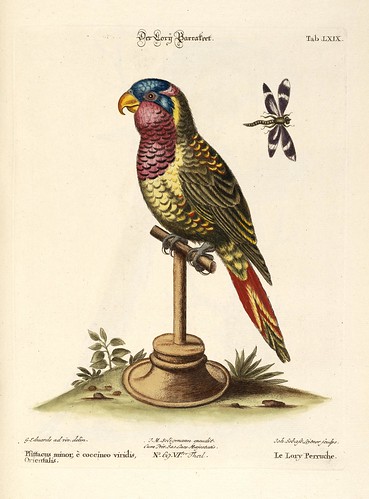

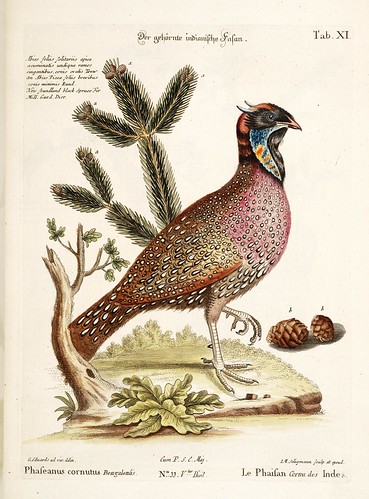

Following Catesby

'Verzameling van uitlandsche en zeldzaame vogelen :benevens eenige vreemde dieren en plantgewassen : in 't engelsch naauwkeurig beschreeven en naar 't leven met kleuren afgebeeld /door G. Edwards en M. Catesby. ; vervolgens, ten opzigt van de plaaten merkelyk verbeterd, in 't hoogduitsch uitgegeven door J.M. Seligmann ; thans in 't nederduitsch vertaald en met aanhaalingen van andere autheuren verrykt, door M. Houttuyn.' 1772-1881.

Drawn by G Edwards (after Mark Catesby), engraved by IM Seligman, JS Leitner et al. Available from the Botanicus website (there are three 'sets' of illustrations: general birds, parrots and animals; easily found from the drop-down menu in the margin).

The above selection and a few others have been saved in this set. These constitute probably a quarter or less of the total number of illustrations in the book. If you look closely, there are occasional eccentric additions to the design of the above pictures, beyond the usual 18th century stylising. Botanicus appear to have digitised a second copy of the same(?) work: see here.

Friday, July 25, 2008

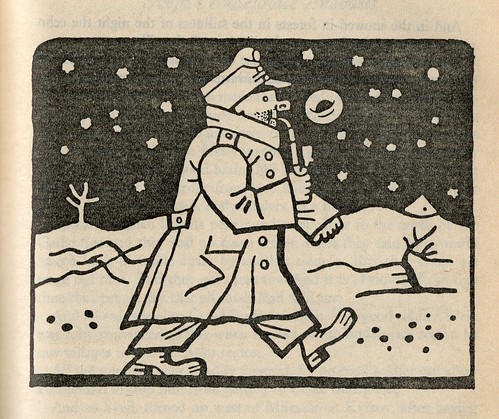

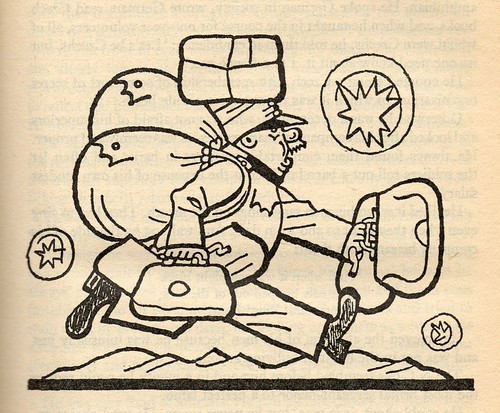

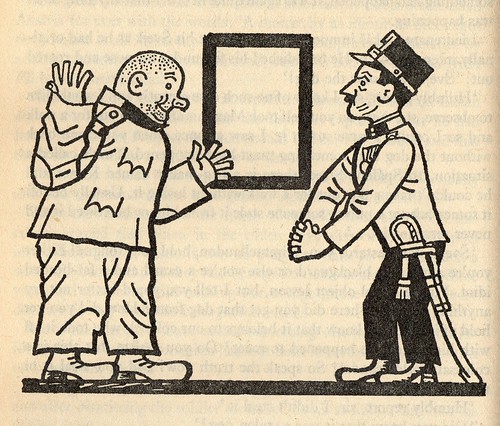

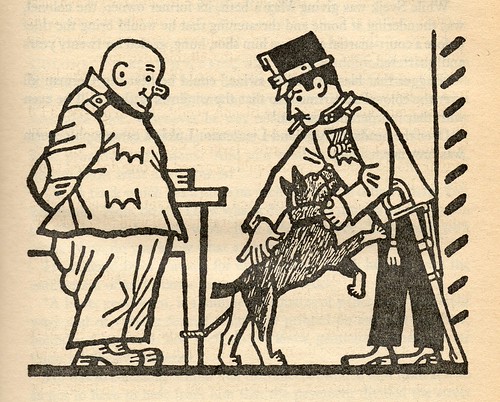

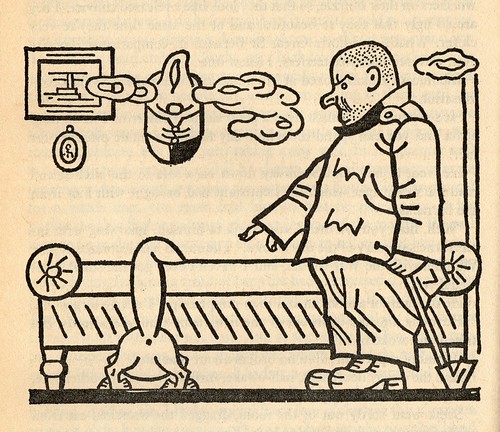

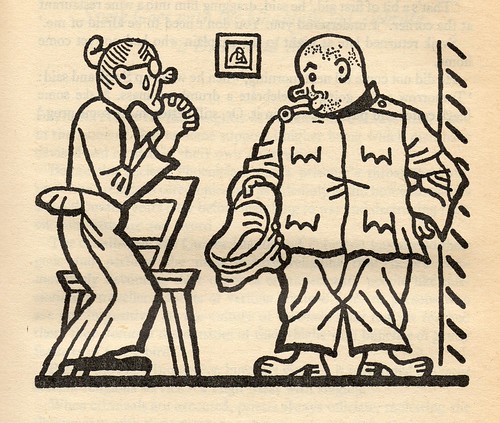

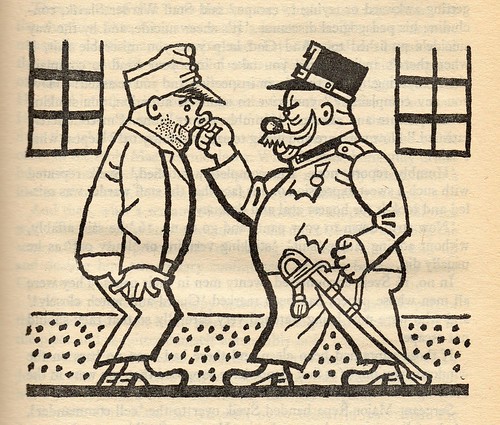

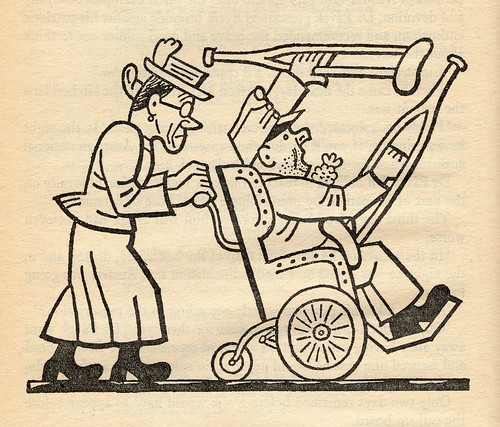

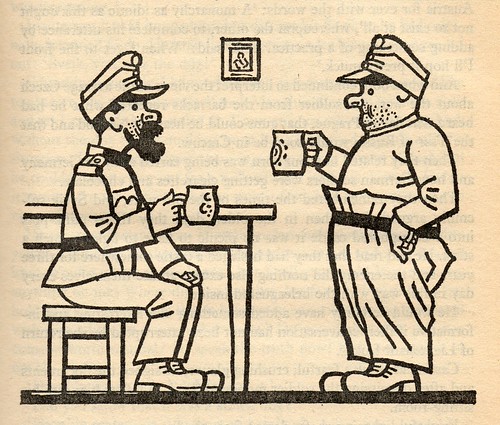

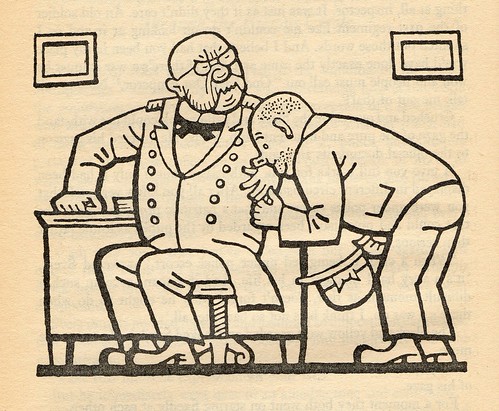

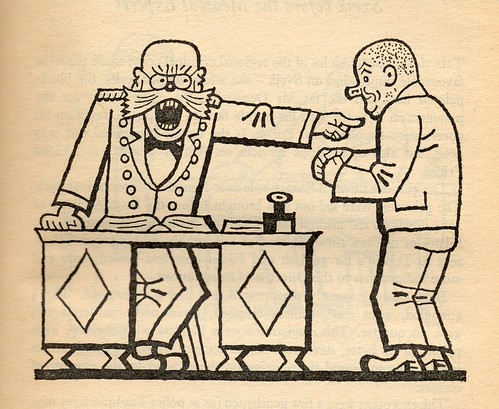

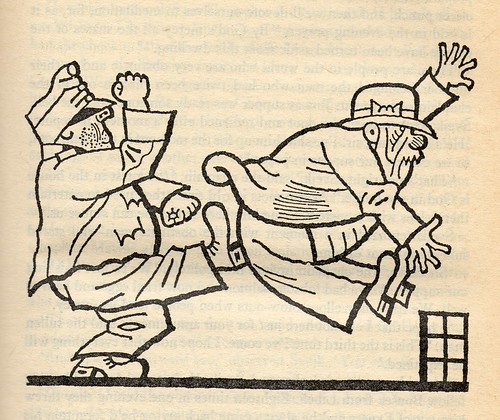

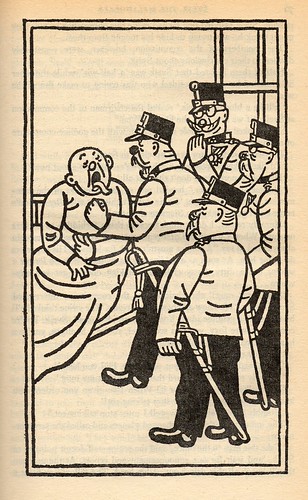

The Good Soldier Švejk

My elder brother had a significant influence over my tastes in music (especially) and reading when I was growing up. I remember being in my Agatha Christie 'phase' when I was about twelve years old and eyeing off A's big yellow Penguin book with a foreign name in the title and a humorous caricature on the cover. I wondered why it held his interest and why I heard him laughing so often from his room when he was reading.

It took me a couple of years before I discovered for myself the pleasures of Jaroslav Hašek's unfinished satirical masterpiece, 'The Good Soldier Švejk' (pronounced: shvayke). It had begun life among a series of humorous short stories published just prior to World War One but was expanded by many orders of magnitude towards the end of Hašek's life. In the early 1920s, serial excerpts appeared in magazines, but the definitive version of his magnum opus was published posthumously in 1923, after Hašek had succumbed to tuberculosis.

That Hašek (1883-1923) was from Bohemia was entirely appropriate. If ever there was a fellow that deserved the descriptor, bohemian, it was he. Anarchist, wanderer, journalist, soldier, bigamist, political absurdist, practical joker, artful dodger and non-conformist doesn't even begin to scratch at the surface of this Czech eccentric's unique character.

Many of these traits found their way into the persona of Hašek's great protagonist of modernist literature, the guileless and bumbling (or is it brilliant and subversively crafty?) Josef Švejk. He appears to be so over the top enthusiastic in his desire to serve the Austro-Hungarian state at the outbreak of World War One - the book's opening - that noone he encounters can decide if he is intent on sabotaging the war effort with a flamboyant masquerade of pedantic literalness, or whether he's merely a fool with a penchant for storytelling.

At its most basic, 'The Good Soldier Švejk and His Fortunes in the World War' deploys the peculiar characteristics of its eponymous everyman star to highlight the folly of war and the absurdity of bureaucratic imperialism. It is also a tour de force in terms of language (yet still very accessible), occupying its own place in the pantheon alongside epic tales from the likes of Rabelais and Cervantes. In literature, Švejk is to WWI what Yossarian (from Joseph Heller's 'Catch-22') is to WWII. Švejk is in fact the progenitor of the latter; Heller admitted that his own creation would not have come about had he not discovered Hašek's book.

"‘Great times call for great men,’ Hašek explains in a brief, ironic preface, but goes on to state that ‘the great’ are the reverse of those who act with the precise intention of having their names in the history books. He describes his hero Švejk as ‘heroic and valiant’. But Švejk performs no actions which those two words are typically used to describe. It becomes clear that Hašek, by means of his enigmatic hero, is attempting to redefine certain key values. Švejk comes to be seen as a ‘good soldier’ in political rather than military terms because his stubborn incompetence has the effect of destabilizing and exposing the absurdities of imperial rule. The implication is that the form of political disruption adopted by people like Švejk – complete resistance which takes the form of utter compliance – has been instrumental in the post-war liberation of the Czechoslovak people after four centuries of imperial domination.Hašek had met the illustrator Josef Lada [previously] but he was never to see the wonderfully adroit, thick lined caricatures that were commissioned in 1924 (and after) and which have become a visual shorthand and personality extension for the novel itself. I have never been to the Czech Republic but I gather that Lada's Švejk remains a popular and widespread motif (eg.).

There is a curious contradiction, then, between the imputed historical importance of Švejk’s actions and the seeming imbecility of those actions themselves. The problem is resolved if we remind ourselves that Švejk is not a conscious political actor. The historical effect of his actions has nothing to do with a wish on his part to be historically effective. Švejk’s main motive is personal survival. But the wish to stay alive is by definition counter to the army’s need for willing cannon fodder. Švejk is thus a thoroughly destructive spanner in the works. Nothing proceeds smoothly when he is present. Even the story, of which he is the hero, cannot progress because he keeps dragging it down the cul-de-sacs of his interminable anecdotes." [Macdonald Daley]

There have been a number of books in my life that have provided rewards beyond the obvious reading pleasure. I've always tried to keep on hand pristine copies of Plato's 'The Symposium', Ben Okri's 'The Famished Road' and Hašek's 'The Good Soldier Švejk' (among a few others), because it's so enjoyable matchmaking amazing - to me anyway - reading material with potentially like-minded people who have not come across the books before. The after-smile makes it all worth it of course.

But on this occasion, I'm going to have to get myself a new 'Švejk' because flatbed scanning one third of the book's illustrations has left my decade old copy in several pieces and very far from pristine. There are fifty three illustrations in total in this set - the image title scan numbers are sequential with their order in the book - scanned at 600dpi (overkill for such bold line drawing, I guess, but it gives good quality and very large image files as a result, so there's that) [the illustrations are not in book order above]. Now that I've got a disarticulated book that's perfect for scanning, I may continue with the venture somewhere along the line in the future. [note to self: last scan from p.267]

- The best Švejk site: Švejk Central.

- Dr Jan Culik on Jaroslav Hašek.

- 'The Good Soldier Švejk and His Fortunes in the World War' translated (and introduction by) Cecil Parrott.

- Some Josef Lada links in the previous post.

- wiki/wiki, if you must.