Christine de Pizan (Pisan) (c.1363-1430) was raised among the nobility of Paris and pursued intensive studies in literature, history, languages and the sciences.

Towards the end of the 14th century, Pizan took up writing to support her three children, following the death of her husband. She is widely credited with being both the first professional female writer, and first feminist to advocate for her sex, in all of Europe.

Her writing career might be considered to have had two phases: poetry, then prose; and she achieved great renown during her lifetime. Between 1393 and 1412, Pizan composed more than three hundred ballads, and even more shorter poems. She was similarly prolific in longer form, having written some fifteen books and numerous essays by 1403.

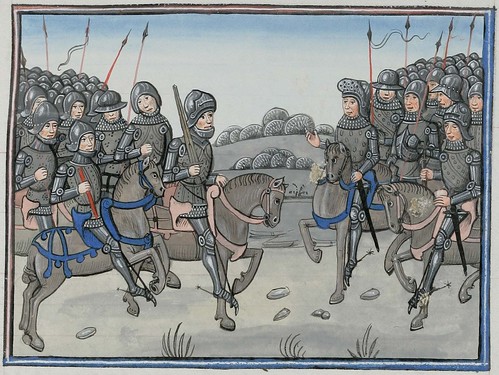

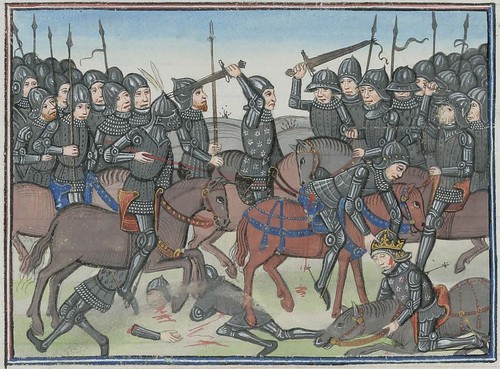

"Her poetic work is notable both for its technical mastery of the accepted forms of her time, and for its innovativeness. Christine excelled in the complex metrical forms of courtly poetry: ballads, lays, and rondeaux. She also went well beyond the conventions of her time by integrating personal, political, moral, religious, and feminist themes within those structures. [..]Othea's Epistle to Hector (the Book of Knighthood) is a work of moral instruction in both verse and prose. It describes the spiritual and moral education of a young knight, Hector, in the form of an allegorical story.

[Pizan] combined extensive historical knowledge with a deep concern for the political and social issues of her day [and she] expanded and developed many of the themes first introduced in her poetry. The importance of responsible government and political ethics; women's rights and accomplishments; and religious devotion, appear consistently as themes throughout Christine de Pizan's writing."

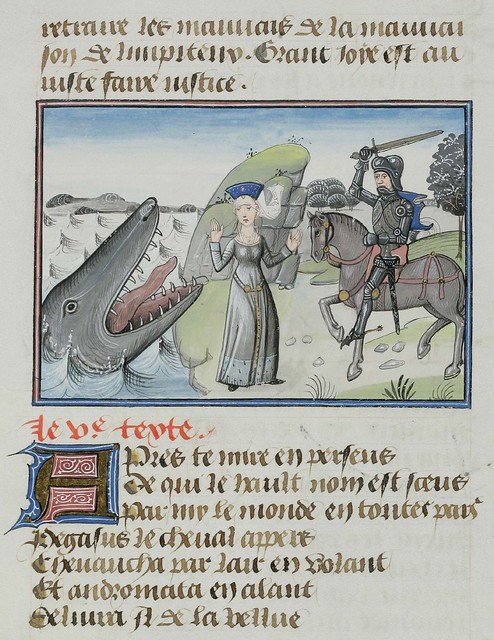

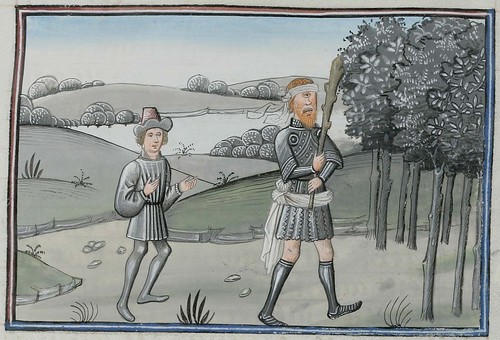

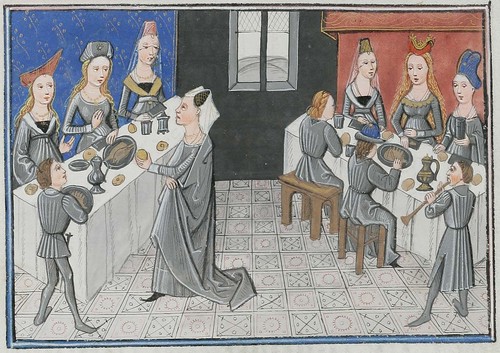

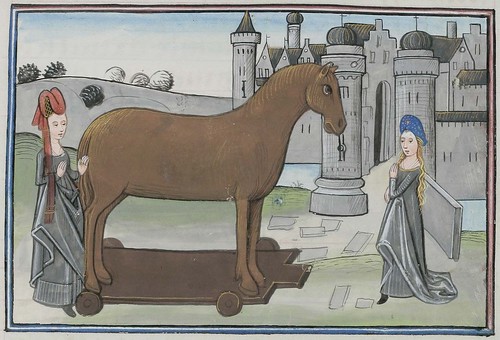

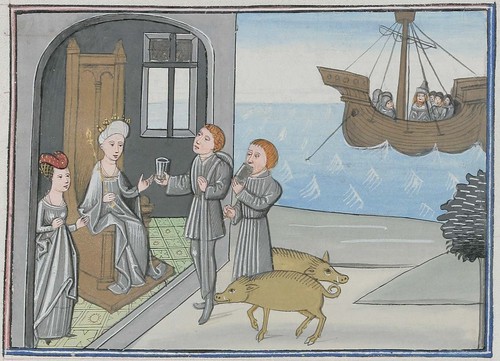

"'Épître d'Othéa' takes the form of a letter written by Othea (a goddess who symbolizes wisdom and prudence) to the Trojan hero Hector. The letter is divided up into 100 chapters, each consisting of a miniature illustration and a verse text recounting a story from classical mythology, a prose explanation designed to expound the moral significance of the story, and finally a prose allegory expounding its underlying spiritual/Christian interpretation." [source]The present parchment manuscript of 'Épître d'Othéa' was commissioned by the bibliophile Antoine de Bourgogne in 1460 and was written in Middle French, with the full complement of exquisite miniatures. Gold highlights can be seen in (at least) the opening full page decorations: the first image up above.

Incidentally, Pizan retired to a convent for the last twelve or so years of her life emerging only once - in the writing sense - when she circulated a poem in 1429 in support of Joan of Arc (d. 1431).

- 'Épître d'Othéa' [Cod. Bodmer 49 Pizan] {Cologny, Fondation Martin Bodmer} is available online through e-codices, the Virtual Manuscript Library of Switzerland. [http://www.fondationbodmer.org/]

- An alternative contemporary set of Othea Epistle miniatures is available from Meermanno Museum in The Hague : these include descriptions of each in English (that I was too lazy to marry up with the example miniatures seen above).

- Christine de Pisan at The Middle Ages.

- Christine de Pizan: Wikipedia, New Advent, CSU Pomona, UPenn.

- Tangential: Christine de Pizan The Making of the Queen's Manuscript at Edinburgh University Library.

- 'The Epistle Of Othea To Hector: Or The Book Of Knighthood' (1904).

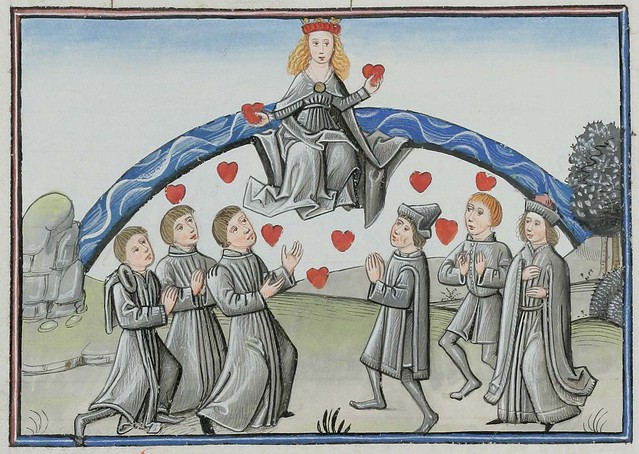

These are lovely, wonderfully odd, and with very attractive use of colour. The cyclops image, for example, does a great deal with shades of grey and little else. There's also a curious motif of women descending from the skies. That hasn't happened to me yet.

ReplyDeleteThis is stunning, and seems to be well-preserved. The colours are quite vivid for their age. Thank you for posting this and helping make the Internet the world's largest cultural museum. :)

ReplyDeleteWhat a curious and wonderful work! Thanks for sharing it with us here. Hats off to the generations of people who worked to preserve this extraordinary document.

ReplyDeleteCaptions, please. It would help a great deal to have a clue as to what is going on, though I do get the Trojan Horse. Quite lovely.

ReplyDeleteThanks.

ReplyDeleteYes, I've been waiting all my life for women to fall from the sky. I've also been waiting to win the lottery and be elected Emperor of my own country.

Naupilon, you will note among the links at the end of the post assistance in finding an appropriate caption. It would be grand of you to compile the list and post it here as a comment.

It's not Anton von Bourgogne, but Antoine de Bourgogne (1421-1504), le Grand Bâtard. He was a bastard son to duke Philippe le Bon (the Good).

ReplyDeleteThanks Tiecelin, I've changed it. That was the name given by the (German) Swiss manuscript site.

ReplyDeleteApparently, one of the miniatures (not shown up above) "contains the dedication of the work and shows four figures, identifiable as Philip the Good, Charles the Brave, and the two noble bastards David and Anton of Burgundy."(sic).

Peacay, it would have been pleasant indeed to live in a world where women descend from the sky, but if you follow your link to the site with the English captions, you'll read: "Diana, guardian of chastity, speaks with maidens." So this land may not be quite the bargain you envision.

ReplyDeleteApart from that, I found the captions almost as strange and magical as the pictures, and well worth the effort ("Minerva, inventor of armour, gives it to soldiers.") What a cool book!