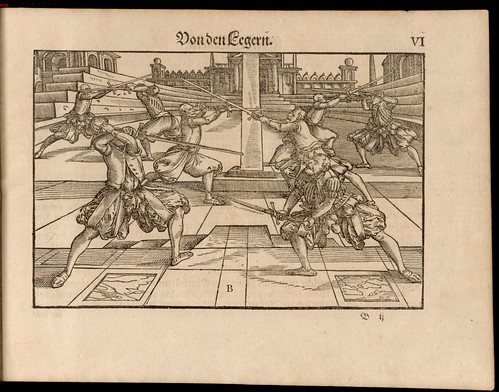

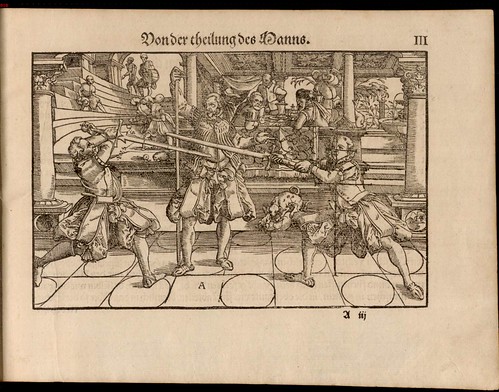

'Gründtliche Beschreibung des Fechtens' (approx: Background description of fencing) by Joachim Meyer was published in 1570 and is available from the Bavarian State Library. (click 'Minaturansicht' for thumbnail images) A second edition version from 1600 is also available.

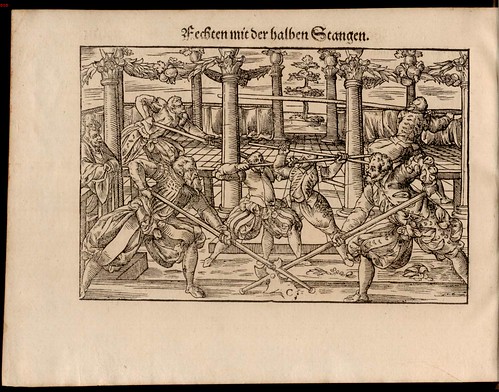

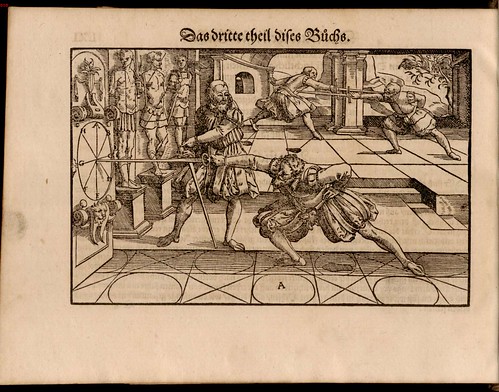

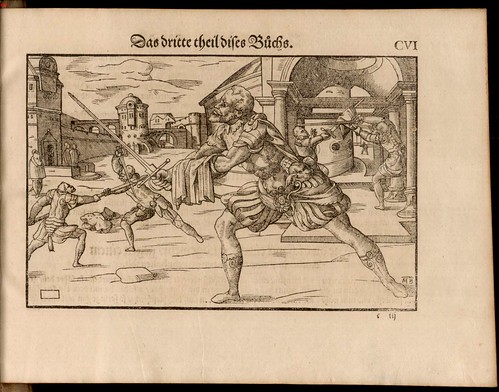

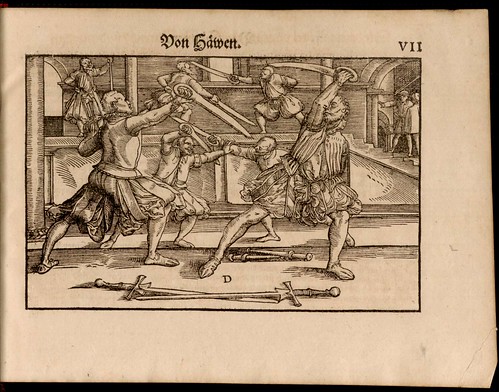

"Meyer was a professional master-at-arms of the Strasburg Marxbrueder fighting guild whose important work, 'Kunst der fechtens' ("Art of Fighting") was produced in 1570. His stunning work (illustrated by Tobias Stimmer), "A Thorough Description of the Free Knightly and Noble Art of Fencing", focused on the entire arsenal of weapons: langenschwert, shorte-sword & dagger, Dusack*, long & short staffs, pole-arms, dagger, Pflegel (flail), and wrestling. While the architecture and backgrounds of the woodcuts are fictional, the figures are literal. Meyer also included a section on the new rapier & dagger largely compiled from Italian works such as Viggiani and Di Grassi."

*the peculiar, machete-like training weapon imported from Bohemia

- Transcription (in German)

- Wikipedia/Nationmaster.

- 'The Art of Combat: A German Martial Arts Treatise of 1570' (2006).

- Previously: Academy of the Sword; Paulus Kal: Kunst des Fechtens I; Paulus Kal: Kunst des Fechtens II; The Art of Fencing; Fight Club; combat tag.

----------------

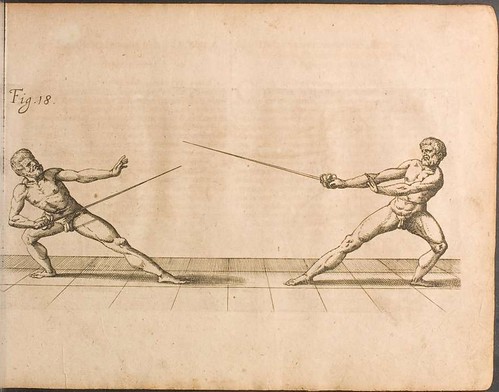

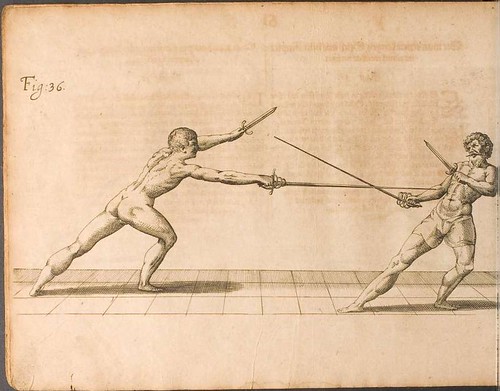

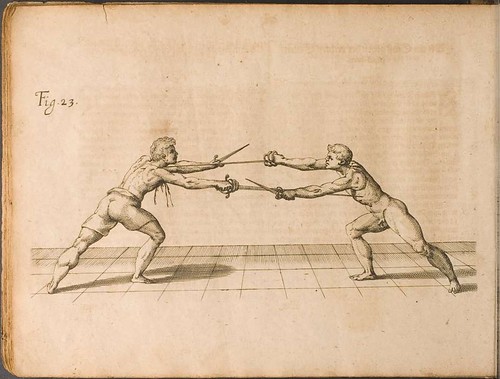

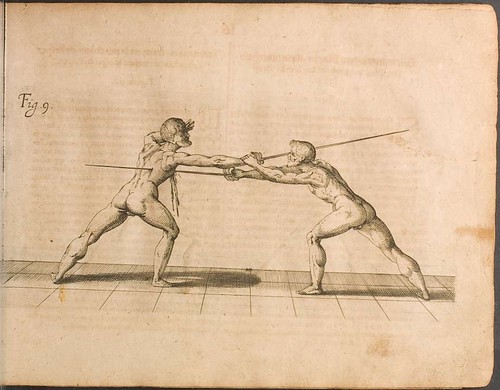

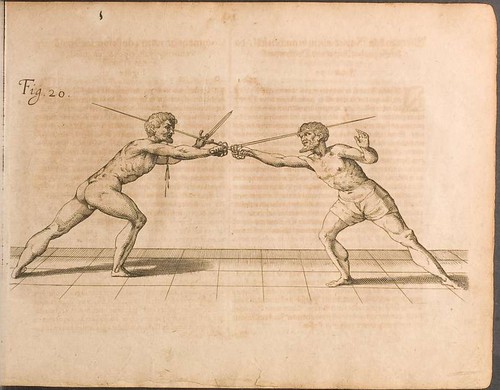

(below) 'Fecht-kunst' by Nicoletto Giganti, 1622 is available from Wolfenbüttel Digital Library. {this is the German translation of the original 1606 rapier manual called 'Scola overo Teatro'}

Best known for fully describing the lunge, Giganti was a fencing master from Venice. He is thought to have also plaigiarised a rapier manual by Savlator Fabris (I don't think it's this one below) in 1606. There's not too much around online.

- Wikipedia.

- Italian rapier from swordwiki.

- Just because I found it: 'Parallels between Fencing and Dancing in late Sixteenth Century Treatises' by Dr PJ Pugliese, 2005 [6Mb pdf]

I was going to say that the first set could serve as advertising for pantaloons as well as instructing the martial arts, but then my attention was caught by the second set. Nude fencing? I mean, I realize that there was something of a fashion for pictures of nude men fighting (I am unsure exactly why, but could speculate), but why the battle of the nudes versus the dudes in shorts? And why so many of them pierced through the eyeball and bleeding without anyone falling down dead?

ReplyDeleteI know, I know, yet more questions. Eternal torment.

Re the above, I see that the third image down on last year's fencing post also features the mystifying theme of nude vs pants-wearing combatants, although there the nudes are draped a bit and the pants look less like underwear. Given the smaller size of the combatants and the profusion of other imagery to deal with, I'm not surprised this didn't strike me at the time.

ReplyDeleteYeah. I have nothing else to do this weekend. Back to the slice-and-dice.

Great images, though naked fencing seems rather masochistic...

ReplyDelete"What sympathy can be felt by a Frenchman of today, who has himself carried a sword, for men who fight stark naked?" --Stendhal, from "Salon of 1824"

ReplyDeletePeople did not actually fence naked... A noble of this period (i.e. someone who could afford swords and books about sword fighting) would not leave the house not clothed like a gentleman of his stature.

ReplyDeleteItalians in the renaissance were obsessed with the human body, the form, musculature, etc. and drawings were often painstakingly accurate in proportion and detail--look at most of Leonardo da Vinci's works. The books of Italian sword masters of this era (Gigante, Capo Ferro, Fabris, etc.) often were illustrated with nude or mostly nude models because the theory was one could not study the proper form and technique without being able to see every detail of the body. Contrast this to the German texts (Meyer, Liechtenauer, etc) or even earlier period Italians (Marozzo, dall'Agocchie, Manciolino) where the publications of their works depict clothed models.

Also remember, much of our society's feelings of shame, embarrassment, or aversion towards the naked human body were not as ingrained until well after the Elizabethan era.