How do I love thee

Let me count theways snails..

Let me count the

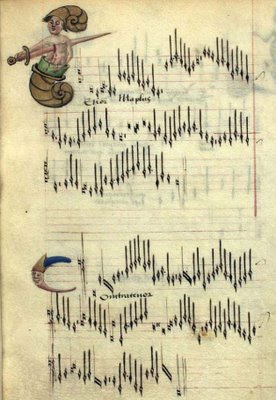

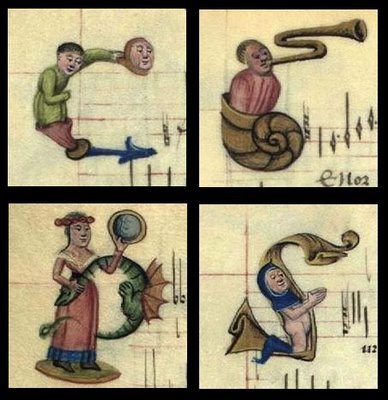

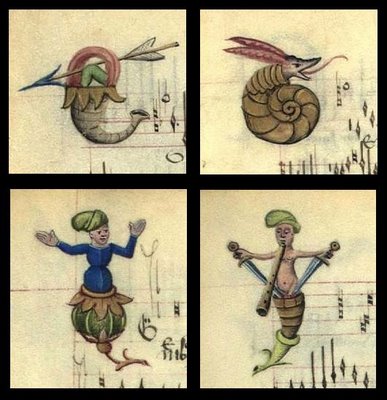

Is there some esoteric medieval connection between love and escargots (not involving garlic) that I'm missing? Or do snails evoke music making devices like the wind instruments and conch shells? Odd, very.

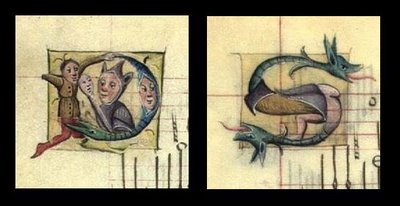

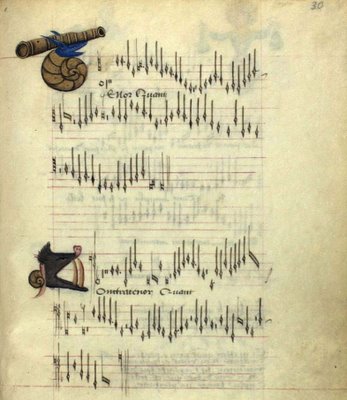

The french-burgundian parchment manuscript, 'Chansons d'Amour' - also known as 'The Copenhagen Chansonnier' [Thott 291 8º] - was produced in the late 15th century. It consists of illuminated scores for 30 love songs, arranged for 3 voices.

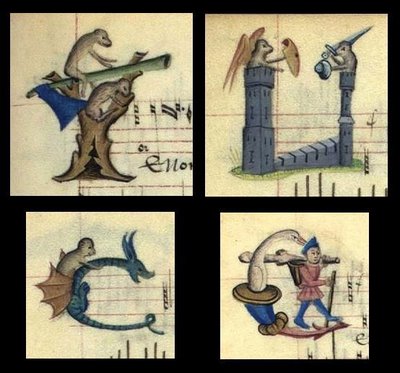

The french-burgundian parchment manuscript, 'Chansons d'Amour' - also known as 'The Copenhagen Chansonnier' [Thott 291 8º] - was produced in the late 15th century. It consists of illuminated scores for 30 love songs, arranged for 3 voices. The Danish Royal Library, who own and host this work, regard it as the most "interesting and valuable" among their musical manuscript collection. [LINK UPDATED Nov. 2013]

The Danish Royal Library, who own and host this work, regard it as the most "interesting and valuable" among their musical manuscript collection. [LINK UPDATED Nov. 2013]The whimsical lettrines and caricature adornments kept me smiling, paging through this ~44 page work. Love likes a sense of humour. I've posted less than half of the illustrations, I would think, with the occasional touch up to artefact.

Fabulous—thank you!

ReplyDeleteME PARECE GENIAL BIBLIODYSSEY, CADA DIA ME SORPRENDEIS MAS. UN ABRAZO POR LA LABOR Y EL CONOCIMIENTO QUE DA.

ReplyDeleteGRACIAS

i love those snails with wings!

ReplyDeletegl. from scarlet star studios

I've never actually seen period music with illuminated clefs! The snails are the visual cue for the clef markings!

ReplyDeleteCheers.

ReplyDeleteThanks cavalaxis - I had been wondering about that. There's very little online (that doesn't require subscription) about the french-burgundy chansons.

And I just noticed that 'lettrine' is not even recognized as a word in any of my english dictionaries. Now that's strange. I propose we co-opt it. So much easier than 'illuminated letter'.

You've given me a whole new understanding of clefs.

ReplyDeleteStunning--I have studied this repertory on and off and not come across this MS before. You might want to take a look at the Chansonnier Cordiforme (Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale, Rothschild 2973), an amazingly beautifal song manuscript in the shape of a heart. The music in that collection is just a little bit earlier, but still basically the same repertory.

ReplyDeleteThanks mfox04 - I have a funny feeling (not yet checked) you have given me the lead to find the book from which I posted an image a while back but couldn't recall where I had seen it.

ReplyDeleteI'll remember that, cheers.

I don't know what cavlaxis is referring to. The clefs are not illuminated at all. They are quite present after each illuminated initial. The initials are either of the first word in the verse under the Cantus line, or the initial of Tenor or Contra. The rest of the word follows, for instance illuminated T, Enor under the staff.

ReplyDeleteThe clefs don't resemble modern clefs all that much: if the G clef was used, it resembled a capital G centered on the bottom or second-to-bottom line with additional ornamental lines (which eventually became the spiral and ornamental rise and fall of our modern G clef). The C clef looks like a doublestop: two breves centered in the spaces for B and D, with one line joining them on the left. Since breves are two heavy horizontal lines (forming the top and bottom of the rectangular note) and light lines at either side (the thickness being a direct result of the wide nib), the clef indicates that C falls between the two given notes. When centered on the middle line, it is the equivalent to our Alto clef. On the second to top, it is equivalent to the tenor clef, and on the bottom two lines it is mezzo and soprano clef, usually used for the Cantus. The F clef, on one of the top three lines, is a long (a breve with a long descending tail on the right) with two minims (lozenge-shaped or diamond-shaped notes with tails) stacked, as the breves in the C clef, above and below the line that indicates F. So with the F clef, the long sits centered on F and the two diamonds that follow straddle it. I have never, ever, seen illuminated clefs: it would be horribly counter productive (their intention is to unambiguously tell where the reference note is!)

For more along this line, Dijon 517 (as it is called bibliographically) contains much more of this repertoir, plus some later works in four parts. A black-and-white photo-facsimile (no attempt at being a real facsimile) has been made, and is available in some music libraries. (The first one I found was in the Ithaca College music library, but that was in 1972.)Many of those initials are illuminated, also, and none of the clefs are.

An interesting aside, Petrucci's first book of polyphonic music printed using moveable type was first offered in 1551. It contained a selection of Burgundian 3-part motets and chansons, along with the more 'recent' style 4-part pieces. It also contains 8-11 "si placet" pieces (depending on who is counting): these are 3-part pieces to which a fourth part has been added. The old contra (usually) becomes a Bassus part, and the new part is usually termed Contra. Sometimes these were written by the original composer, sometimes by other composers. They have the appearance (especially by their affect on the original modes and harmonies) of "updating" the piece to more modern tastes, an early example of recycling!

Thanks very much for your comment Raybro. I guess it's fair to say that for the majority of us, medieval music manuscripts are very esoteric and we struggle to understand visual aspects from a modern and often ignorant (me!) standpoint.

ReplyDelete@raybro: You're right, they must be section letters. To my modern interpretation, I expect the clef to be the dominating symbol on the staff. I can see now the moveable clef symbol... Thanks!

ReplyDeletePerhaps they knew that snails were aphrodisiacs? It is very peculiar.

ReplyDeleteIt's a bit hard to search with 'medieval snails aphrodisiacs' (or permutations on that theme) but that seems as likely an explanation as anything.

ReplyDeleteAmazing. As librarian/searcher-of-things I can only imagine how much work you've devoted to this incredible website. Thank you.

ReplyDeletePS The url has changed. This will take one to index of this item:

ReplyDeletehttp://www.undoulxregard.org/copenhague/copenhague.html

Thanks so much ariel. I've updated the link. (Sooooo sooooooo long ago - I admit to only having very vague recollection of handling/dicing/splicing the images now)

ReplyDelete