"I take him to be wholly a Brute, tho' in the formation of the Body, and in the Sensitive or Brutal Soul, it may be, more resembling a Man, than any other Animal; so that in this Chain of the Creation, as an intermediate Link between an Ape and a Man, I would place our Pygmie."

“one would be apt to think, that since there is so great a disparity

“one would be apt to think, that since there is so great a disparitybetween the Soul of a Man, and a Brute, the Organ likewise in

which ’tis placed should be very different too.”

[click for full size versions]

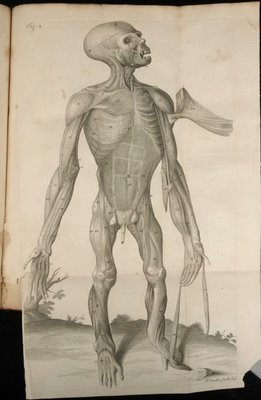

Edward Tyson (1650–1708) was an English physician and member of the Royal Society. Beyond his medical duties and publications (both of which were significant and extensive) he had a deep interest in comparative anatomy, an area of scientific investigation in which he is one of the leading early protagonists.

In 1680 he had already outlined this interest in 'Phocaena or the Anatomy of the Porpess' in which he not only systematically described cetacean structures but also wrote of "the importance of a comparative approach to anatomy and attempts to develop a plan for a natural history of animals." He performed dissections on many different species and published his findings in the 'Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society'.

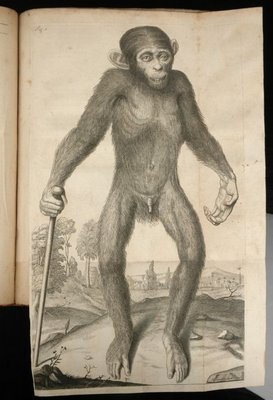

In the late 1690s a chimpanzee had only been seen illustrated in Europe once previously and the larger apes such as the orangutan and gorilla were not discovered or described until the 18th and 19th centuries respectively. It was not surprising therefore that Tyson was given the opportunity to dissect a chimpanzee that had been brought over from Africa in 1698.

The chimpanzee was a juvenile (which led to some erroneous anatomical statements) and was injured on board its transport ship. The injury later became infected and caused the chimp's death. This injury is either directly or inadvertently represented in the engraving above (all the drawings were done by the anatomist William Cowper) in which the bipedal chimp is seen using a walking stick. Tyson described the animal as quadru-manous to distinguish it from the quadrupeds.

The reference to 'Orang-Outang' in the title is only in terms of it meaning "man of the woods" [homo silvestris]. So it was that 'The Anatomy of a Pygmie' marked the beginning of primatology, and there is some irony in Tyson having been a distant cousin of Charles Darwin. I haven't searched around but I would not be surprised to learn that the expression 'the missing link' derives from Tyson's meticulous documentation of the anatomical comparison between chimpanzees and man.

- The above images have been snagged from a first edition (1699) copy of 'Orang-Outang, sive Homo Sylvestris: or, the Anatomy of a Pygmie compared with that of a Monkey, an Ape, and a Man' on ebay. To the best of my searching capabilities there are no copies online and only a couple of the above fold-out engravings have been previously digitized (and these images above are better quality in my opinion than any others I encountered, including one image at the British Library). I think there were only 8 large illustrations in the first edition so this is nearly complete.

- In addition to the main text, Tyson also contributed 4 essays that were included as an appendix to the book. As the title page intimates, a large part of Tyson's intention when undertaking the project was to prove that mythical dwarf creatures which had been previously described as human were plausible animals, but were in fact apes. The first essay -- 'A Philological Essay Concerning the Pygmies of the Ancients' -- is really a kind of review of 'dwarfian' mythology or historical literature review and is available from Project Gutenburg, with a substantial 1894 introduction by Bertram Windle. It is rather fascinating to skim through.

- Kings College London: 'Anatomy of a Pygmy' exhibition page.

- 'Anatomy of a Pygmie' was re-released in 1966 and a 1967 review by KF Russell is available from pubmedcentral.

- 'Searching for Your Inner Chimp' by Carl Zimmer 2002.

- 'Selected Minor Works: Historical Reflections on Language and Bipedalism' by Justin Smith 2006.

- 'Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature' by Thomas Henry Huxley 1863 at Project Gutenburg.

- 'Four Hands Good, Two Hands Bad' 2006 by Tom Tyler (Senior Lecturer in Communication, Media and Culture at Oxford Brookes University UK).

- This page from Jonathan Marks at UNC Charlotte has a couple of images inspired by those from Tyson/Cowper.

- Previously: comparative mammalian anatomy and historical anatomies.

Is this type of interpretation something we need to celebrate?

ReplyDeleteSimón Dijo, you have taken a quote from a 1699 book that essentially prefigures evolution and recast it as having been written to fulfil nazi methodology of the future.

I think that is a very narrow and disingenuous view and ignores the fact that the quote comes from a detailed and enormously important treatise on anatomy, anthropology and scientific classification methods.

There is no advocacy for racial profiling. There is no intent for the content to be perverted for an alterior service. This was a wholly scientific endeavour and yes, I think it should be celebrated for what it was: the beginning of primatology, the advancement of our understanding of our place in the order of life and an instructive manual for how future scientists would go about approaching the (continuing) problem of classification of apes and humans in the tree of life.

I respect the fact that the concluding message about the chimp was taken in a different context later on by some, but blame shouldn't be sheeted home to the original scientist.

I suggest you go and have a look through some of the supporting links so you can get more of a feel for the incredibly high respect Tyson was held in by both his peers and his patients and you might also get more of a wider appreciation for the importance of the work that he undertook.

We can celebrate E=MC2 without merely vilifying Einstein for the bomb that inevitably followed.

I wonder how much primatology can have advanced from this until the 19th century, having recently happened upon the following, written by Isaac D’Israeli in 1793: “All the ancients are full of strange narratives of Pigmies, who war with Cranes when they arrive on the borders of the Red Sea. It is now confirmed by the accounts of many travellers, that these little men, said to be only a foot and a half in height, are only apes, who fight with the cranes, to preserve their young ones from the attacks of the latter.”

ReplyDeleteI think there was a slow step-wise advance over 2 centuries but this was not helped by Linnaeus in the 1750s when he was said to have disregarded or overlooked Tyson in developing his classification system: essentially naming 2 human species (us and troglodytes).

ReplyDeleteBuffon was an important stepping stone a couple of decades later but it wasn't until Huxley in 1863 that there was a concrete improvement over Tyson's book. As to how long it took for details to filter out to the general public, I guess that process is ongoing.