[uncoloured version]

[uncoloured version]This illustration shows how to deduce the shape of earth

by the nature of the shadow cast on the moon during an eclipse.

(the 2nd and 3rd descriptive notes, although correct here,

should have been switched by the printer in another edition)

Cosmography was a discipline that aimed to mathematically describe the positions of all objects - the moon, sun, stars, continents &c - in the universe. It required a knowledge of cartography, astronomy, geography, architecture, navigation, surveying, astrology and instrument making.

Petrus Apianus (1495-1552) studied cosmography and mathematics in Leipzig and Vienna and began writing short cosmographical works on world geography. By trade he was a mathematician, printer and instrument maker.

In 1524 he published the first edition of 'Cosmographicus Liber' (Cosmographia). He was appointed Professor of Mathematics at the University of Ingolstadt in 1527 and enjoyed favour at the Court of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V for the remainder of his life.

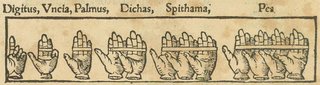

Cosmographia was only mildly successful when it first appeared. It was a sort of layman's introduction to the various subjects making up cosmography, based largely on Ptolemy and without any particularly original content. It describes techniques for measuring and mapping using mathematical instruments in celestial navigation, planetary motion and terrestrial geography as well as explaining more mundane things like telling the time and how to measure distance with hands (see below) and by pacing.

Over the following years medical doctor and mathematician Regnier Gemma Frisius (who would be a tutor to Gerard Mercator) revised, enlarged and corrected Cosmographia and the full 2nd edition was published to great success in 1533. Further editions followed which included some of the first maps of America. The book would remain popular until the end of the 16th century.

Cosmographia contains many woodcut illustrations and includes moveable stacked illustration plates - volvelles - which could be manipulated to make calculations [Volvelle I. Volvelle II. Volvelle III. Volvelle IV]. Apianus's most celebrated work Astronomicon Caesareum came out in 1540 with extravagant and beautiful volvelles.

Now and then sellers of rare books at ebay provide a large number of decent photographs and I try to remember to scan the available works from time to time. So it was that I came across a 1539 hand coloured copy of Cosmographia from which all the above images were lifted. - most, if not all the book illustrations can be seen on the single page (large load).

After some searching I found that Posner Library at Carnegie Mellon University have posted a complete 1533 version of the work (click 'vol0/part0/copy0'). I chose to post the colour illustrations (at full size) in case the ebay pictures are removed. It's a matter of personal taste but I think some illustrations look better coloured and others look better in their original form.

- Oxford University's Museum of the History of Science have an extensive site devoted to Cosmographia (but their images are not so great) which includes explanatory commentary about each of the illustrations.

- Petrus Apianus biography I, II, III.

How beautiful. As imaginative works, they are little novels of the cosmos. It's not clear that we know so much more than this, ourselves.

ReplyDelete