[United by friendship¶]

- click through to much enlarged versions]

As is so often the case on the erratic path taken by this blog, the background to a series of arresting or compelling images - that chooses to randomly dive in front of my passing browser - offers its own fascinating dimension for exploration and provides both context and added depth to the visual subject matter.

On this occasion however, the connection between the imagery and the story is not so much tenuous - although it might be that too - as relatively obscure. The pictures do follow directly from an unusual or at least esoteric episode of regional cultural history, but exactly why the one begat the other is a little beyond my powers of distillation, let's say. Enlightening comments are invited. Inventive fiction will otherwise suffice.

The story begins in the Low Countries during the 15th century with the gradual establishment of drama guilds, a concept that was almost certainly imported from France. These chambers of rhetoric or rederijkerskamer, as they came to be called, developed into companies of amateur actors and authors who wrote and performed vernacular plays and lyrical poetry for the enjoyment of their local townsfolk. From our vantage point you might think of them as a cross between literary societies, political lobby forums and theatre sports.

Early compositions were dominated by religious dramatic and pious verse in keeping with the church fraternity origins of the chambers. Rederijkers (rhetoricians) eventually came to incorporate satire and social and political commentary into their productions. This of course drew the ire of the authorities who essentially tried to manipulate and infiltrate this Renaissance equivalent of the mass media.

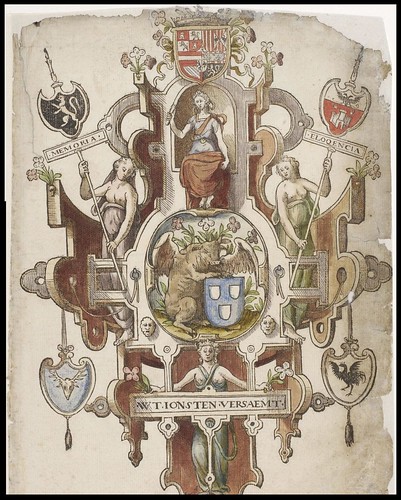

"The influence of the rhetoricians on social and spiritual life, specifically their part in the Reformation, must not be underestimated. Especially in the sixteenth century, the period of their greatest success, they were a factor which both church and state had to take into account.The individual chambers had their own name, slogan and insignia or coat of arms and their plays and performances were affected to varying degrees by local cultural concerns. This apparent provincial quality was tempered by a relative uniformity of structure among all the chambers, with similar hierarchies, rules and prohibitions enforced. The very nature of the chambers also meant that the rederijkers were drawn from a narrow strata of society: this was the literate middle to upper classes, whether in Ghent or Amsterdam or Antwerp (by the middle of the 16th century, virtually every town and city in the Low Countries had at least one chamber of rhetoric). This shared commonality of structure, function and membership probably explains, to an extent, how the chambers were able to exert such a remarkable influence across all the territories in which they were located.

Over the years their power and possessions had increased steadily; they enjoyed the protection of the authorities everywhere, and during festivals and processions they added a splendour which no other guild could offer to the same degree. The magnificence of their performances, the humour and seriousness of their plays, their candid criticism of church and society earned them respect from the magistrates who saw them play in the town hall just as much as from the bourgeoisie who saw them play in the market square."

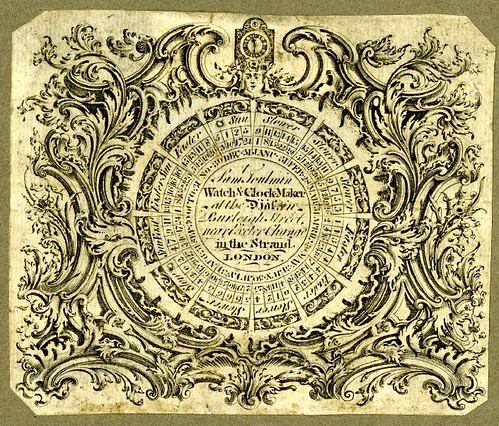

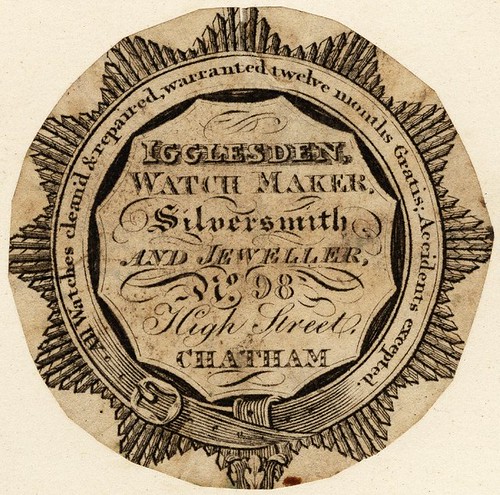

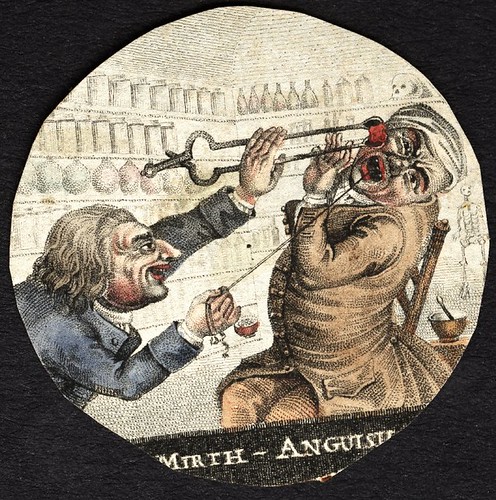

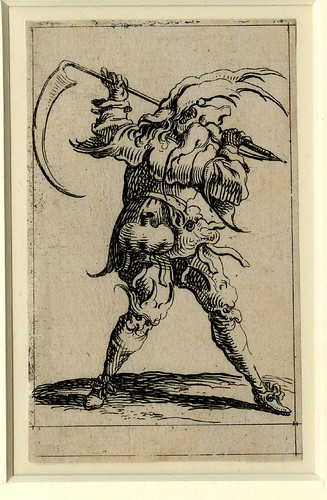

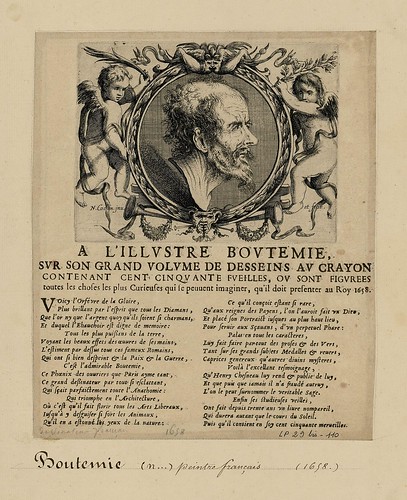

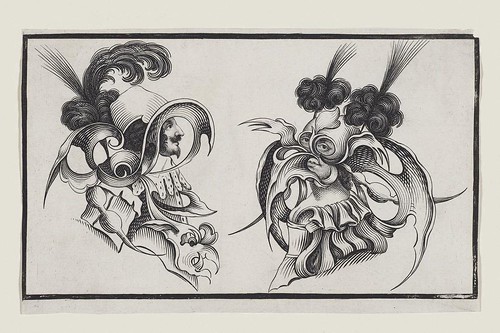

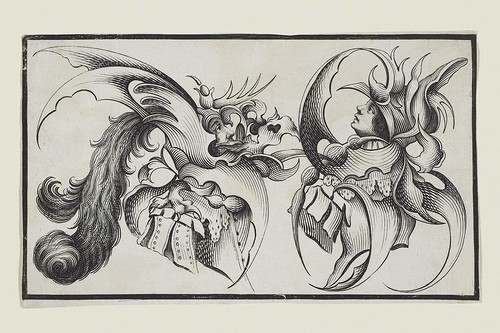

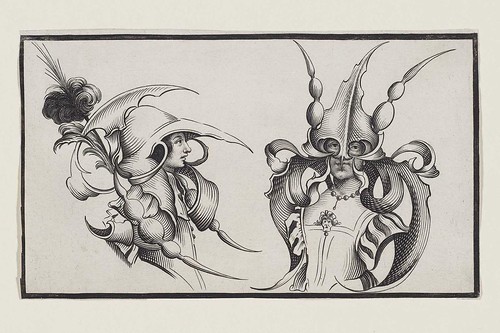

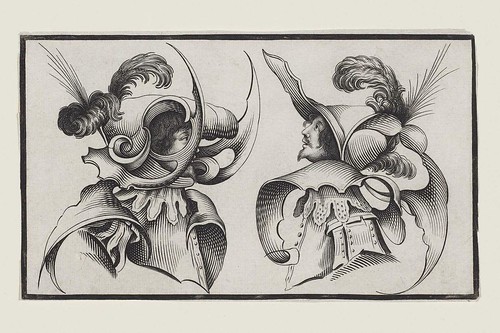

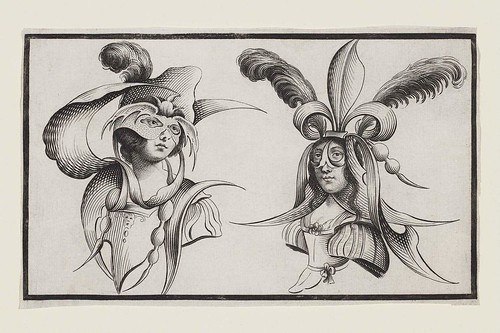

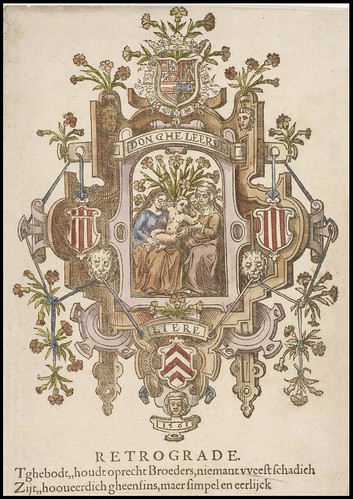

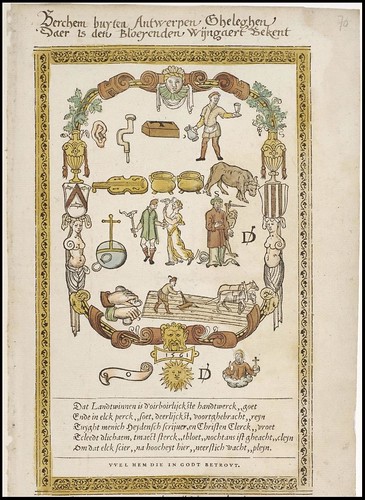

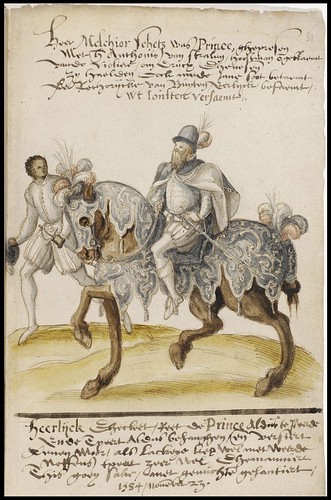

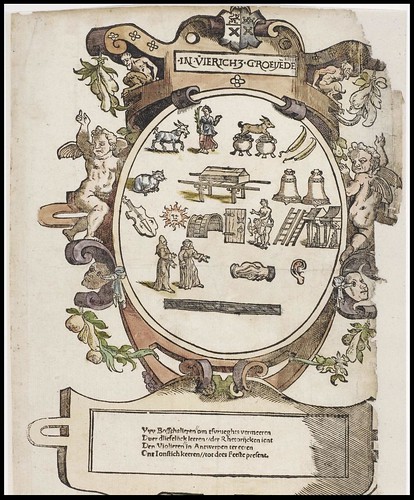

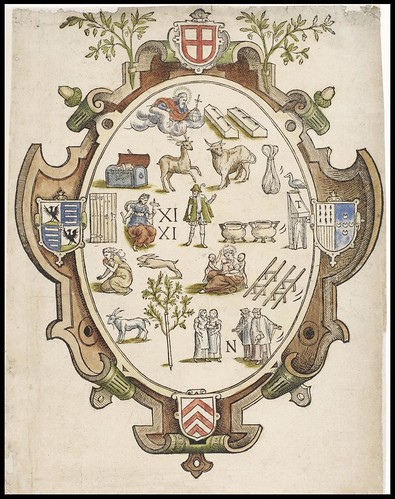

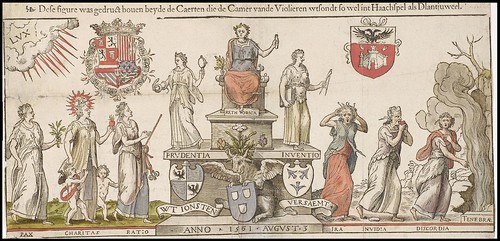

"Formal competition within individual chambers grew into formal competitions between chambers. These competitive festivals, called landjuweels (literally "jewel" or "prize of the land"), pitted cities' chambers against one another in a series of contests strictly governed by rules of form. [..]And what does all this have to do with the trophies, blazons, rebus and allegorical engravings displayed above you might well ask? Good question. The simple answer is that following the Antwerp landjuweel of 1561, transcripts of the plays performed were assembled into book form and a supplement of illustrations (some by Frans Floris), poems and musical lyrics was also produced. A hint accounting for the nature of illustrative material seen in the manuscript may derive from one of the play topics at Antwerp; something along the lines of: which is the greatest motivation of artists? or what best leads mankind to the arts? (referencing the seven liberal arts)

A landjuweel could last for several days or sometimes for several weeks. Performances were open to the public, and by all contemporary accounts, attended enthusiastically. Contestants competed for prizes in a number of categories including: the best play, the best farcical entertainment, the most beautiful blazon, the best acting, the best poem, the best reader of a poem, the best orator, the best song, the best singing, the fool who entertained the best "without villainy"."

This synopsis is fairly inadequate on a number of levels, partly due the lack of accessible material in English (also because it's time for me to abandon it). The rederijkerskamer were a hugely significant phenomenon across a couple of centuries (some variation or another of the landjuweel survives to this day as a festival, most notably in Belgium) and they greatly influenced not only the thinking of the citizens but also helped shaped the development of the modern Dutch language. Because the dramatists were amateurs, their written output became the subject of sharp criticism and mockery since their heyday in the 16th century. Doubtless a modern industry of academic enquiry dutifully puzzles over this and many other aspects of the rederijkerskamer movement.

- Landjuweel de 1561 (in French) is hosted by Belgica: la Bibliothèque Numérique de la Bibliothèque Royale de Belgique. (click 'Feuilleter le document' - it's a flash display and might be a bit wonky depending on browser/operating system) [Dutch site]

- The Rhetoricians ('rederijkers') and their influence on Dutch.

- Landjuweels.

- 'The Reformation' edited by Andrew Pettegree, 2004 (search on 'landjuweel' I think).

- The Antwerp Landjuweel of 1561 and the rhetorician culture of the sixteenth century: (PhD proposal).

- Rare Books Forum on a 1539 account of a landjuweel.

- If you speak/read Dutch, look around because there is a lot of information online.

- ¶Motto of the violet chamber of Antwerp, hosts of the 1561 landjuweel (can also be seen above at the foot of their coat of arms/insignia that features a bull in the centre)